Ahead of his debut at Holland Festival, Glamcult meets the acclaimed producer (and his alter ego).

You probably know Darren J. Cunningham as Actress, the techno mastermind and founder of Werkdiscs—home to the music of Lone, Helena Hauff and Copeland, amongst others. But as his moniker suggests, the acclaimed British producer and composer will take on any role or discipline he deems challenging, the latest earning him a top-billing spot at this year’s Holland Festival.

Commissioned by HF, Actress reimagined Welt Parlament from Karlheinz Stockhausen’s opera aus LICHT, in which politicians above the clouds debate the definition of love. Inspired by the iconic work, Actress actually invited politicians from the UK and the Netherlands to discuss love in times of Brexit, incorporating their words into an ominous composition for voice, piano, electronics and artificial intelligence—and manipulating them live throughout the performance.

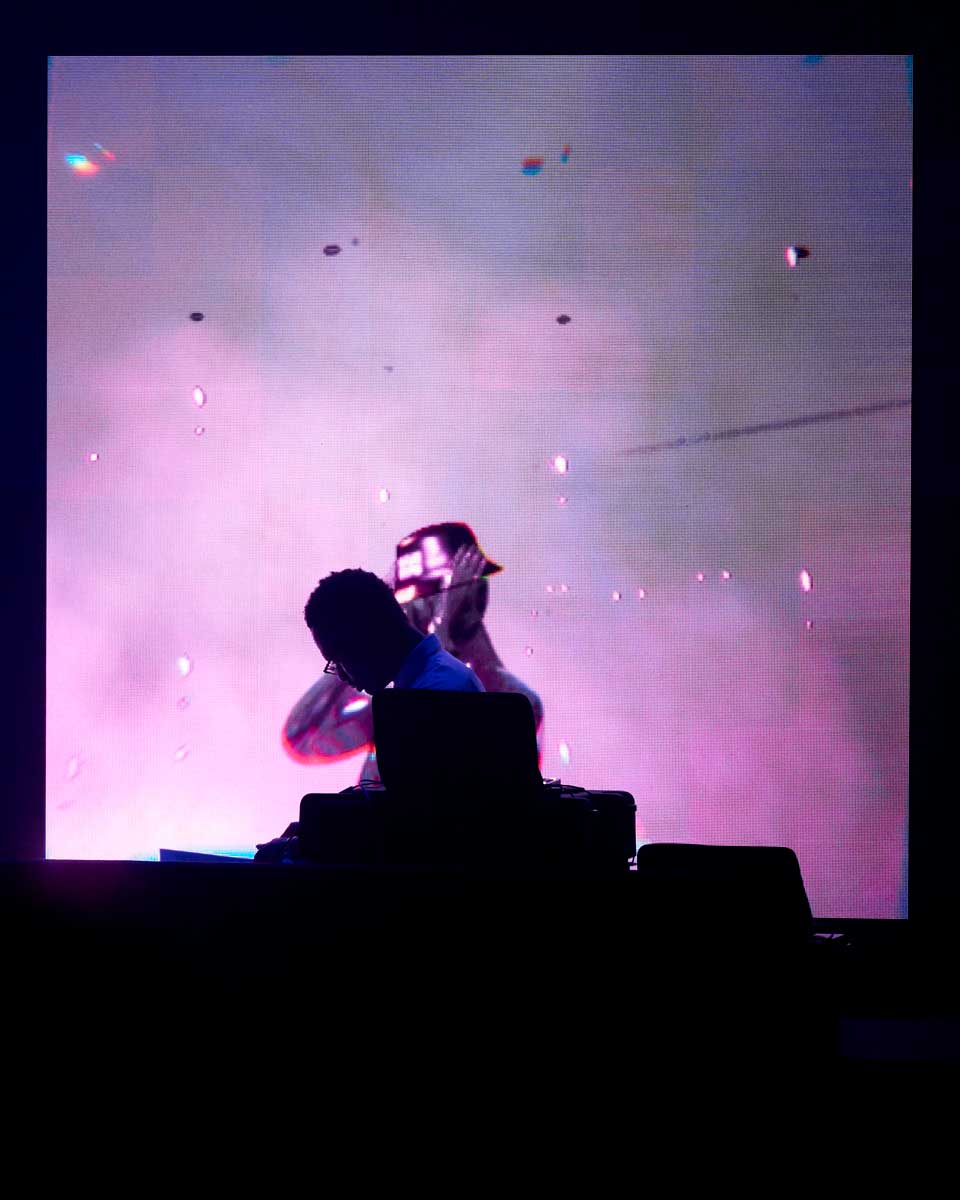

This weekend, Cunningham will join forces with conductor Robert Ames, pianist Vanessa Benelli Mosell, the Netherlands Chamber Choir and Young Paint, his AI sidekick, to bring the original work to Amsterdam. Bent on discovering the story behind the puzzling piece, Glamcult travelled to London for its world premiere and a chat with the maker himself. “It’s a challenge for me as well.”

The way I was introduced to Actress was by hearing Hazyville shaking up Panorama Bar, so it is interesting to see/hear your work in an opera context and in such a different institution. You’ve done crossovers before, but what’s it like for you?

Well, that’s partly where ‘Actress’ comes from. The name allows me to explore all parts of me that authentically relate to my art. My formative years touched on classical music, but then I sort of left classical music and went into electronic music, making dance-orientated or cerebral techno. Then coming full circle and working with orchestras—on a high level, really—not having the formative continued practice, marrying my electronic ideas with acoustic, classical, avant-garde and concrete ideas. This project is very different; it’s opera, which meant that I had to really go inside myself in terms of presenting not just music but text, actions, feelings, moods… being able to interpret those. Someone like Stockhausen was very clear on details. His clarity to detail was something I looked into quite closely.

Honestly, I feel compelled to do this sort of work anyway because I learn more about myself as an artist, individual, as a person. The opportunity to work with and observe other people’s mediums—making what people might call multidisciplinary or cross-disciplinary work. You know, the Holland Festival and Royal Festival Hall gave me the platform to do that and show it to a modern audience. I went to one of Vanessa [Benelli Mosell]’s performances and she’s usually a very conventional piano concerto (playing Debussy, Ravel, etc.) and the audience was very specific to that. I was talking to her manager after the premiere yesterday and he was just overwhelmed, he loved it; he saw the audience and it was completely different. I just like that! You know, my mum and dad were there. They don’t get it, really, but still…

The audience for this piece seems to be very mixed and diverse.

Yeah, that’s really cool! Obviously people know me for my music and they might come expecting something. It’s going to be challenging for them, but it’s a challenge for me as well.

I was listening to the BBC interview where you talk about getting to know Stockhausen and “how far it removed me from anything what I thought music was and ought to be”. Seeing that so much is possible with Stockhausen, what were the parameters or confines within which you wanted to create/compose?

The parameter that I set for myself was to keep it simple, more than anything else. With Stockhausen there’s the potential danger to try and be Stockhausen—which, as an approach, on the face of it, I could have done. But for me it was a question of differentiation of the piece as well, and I had to accept the fact that Stockhausen worked on this piece for a very long time and I worked on it for a much shorter time, having to get inside the score to figure out a way to give it a different perspective. He wasn’t the only composer that I looked at for this piece; I knew that his piece was the central foundation for the final work, but I also looked into other composers whose art I like, such as Jarman and Klein. And I found out there were three central characters: Michael, Lucifer and Eve. These characters gave a lot of scope for a piece that could be dependent on mood.

I wanted to capture a brooding darkness, a sort of science-fiction aspect towards that what Stockhausen was doing. I wanted it to be quite suffocating and tense because a lot of the debates particularly in the UK that I took part in were very tense during Brexit and all that. That was tempered by working with the Dutch parliament, which is a completely different system and much more amalgamated. The contrast between the two was quite stark, so that had to go into the music.

Let’s talk about these debates. The central topic was the definition of love, right?

Yes, I wondered why Stockhausen chose that subject because with politicians you’re never really going to get an answer; politicians don’t do answers! They sort of work around them, that’s what they do as their living. It was fascinating because the first place people go to is try find a romantic idea of love. That wasn’t necessarily what I was looking for, but I was happy for that to come through. Obviously Eve is the more romantic of the characters. But also, there is the corporate aspect, which is leaning towards Lucifer. And then there’s the middle ground that rationalizes everything. There’s always this sort of trinity of power—it’s all related to power, levels of manipulation and control. On the face of it, the debates were probably talking about love but in my head it was very clear that this was about (looking at) love being many different things. It’s illusive, it changes all the times, and it reappears.

When you were listening to these debates or definitions and turning them into librettos, together with Young Paint, what struck you most?

I think the most striking thing was the distance that politicians have from society, how they just can’t see it, and yet there’s a yearning to connect back to it. A lot of the conversation that we had, especially in Holland, involved politicians talking about their childhood and how they got into politics in the first place through trying to help their community. I do feel politicians feel a certain amount of duty, an amount of service—but the political system is driven by corporate finance and big business. With that, there’s inevitably a skewing of all those things. The great thing about art is that it can either really be used as a tool to tell mistruths or as a tool to touch on the truth—but putting it through a lens that’s dramatic, thought-provoking or confusing. To get some sort of visceral response.

At a certain point during the opera I was looking at you in the booth and the choir was getting stuck in this intensifying debate. It felt like you and Young Paint were almost ridiculing the choir (or politicians), by the way you injected sounds and interfered with them. Did I interpret that correctly?

Yeah, I think so. The whole point of the piece is that people aren’t really meant to understand what is being said. It’s meant to be obscured. Generally, when you’re obscuring something, you’re either crossing it out or making it indecipherable in some way, but that’s through language. The musical process really honed in on that idea on obscuring the truth of the debate. There were moments in the UK when the debate was actually very tender. For it to turn into something that was actually quite stark, moody and tense was against how the debate was. For me that was the whole premise of the piece. The transcript, the computer music, was actually reading back aspects of the text but phonetically—slowing it down and changing its dynamics. People didn’t really know what to focus on. And, yes, there was a direct clash between the technology and the parliamentarians. Almost madness, really, reflecting the madness in the UK during these Brexit debates. People losing their minds.

You created and programmed Young Paint, the artificial intelligence. To what extent is it evolving more and more into its own character?

It really is accelerating quite a bit! The more projects we do, the more it is becoming… people who know me, actually, are saying: “He’s just like you!” It’s really weird. It’s all motion-captured, and the longer we work on it, the more it eventually will accelerate to the point where it’s mimicking the things that I do anyway. It’s good for me because I always had a problem with visuals in the sense that they were always in a fixed dichotomy. They never changed and they never truly interacted with the person who’s actually creating the music. What I wanted to translate to people watching me do music is an understanding of the consciousness behind the music. It splits the personality a bit, that’s quite trippy for me as well. And I’ve been doing it a long time now, it’s almost becoming natural.

Actress X Stockhausen SIN {X} II

Friday 14 June 2019

Muziekgebouw, Amsterdam

Get the last tickets HERE

Words by Leendert Sonnevelt

Photography by Denelle & Tom Ellis