“The hunt for peace within our flesh-and-blood homes”

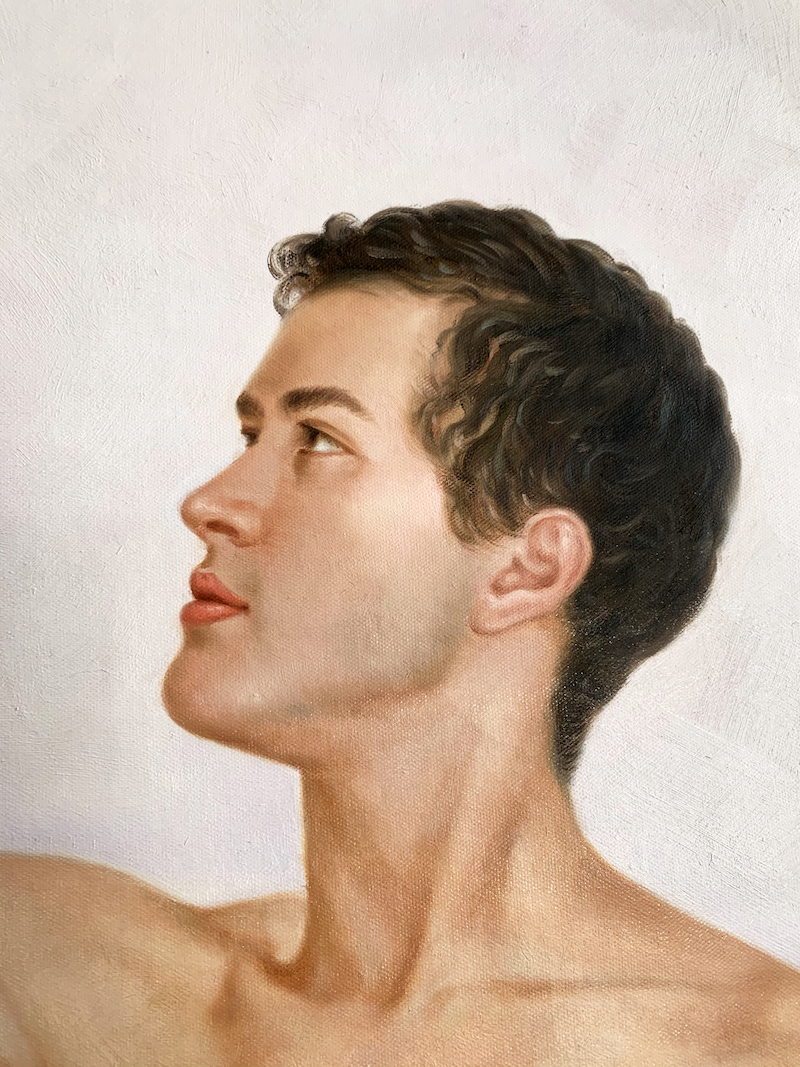

Ouroboros, 2018-2020

During my daily (hourly) scrolls through Instagram, there’s a recurring player illuminating my feed: Stuart Sandford and his homoerotic sculptural escapades. Inevitably, I double-tap, bookmark, and file a mental note in the abyss of an overly saturated editor’s mind. Months later, the holy act of autofellatio reappears in my bank of life’s bigger questions – and I discover myself perusing those saved posts to find Sandford’s piece on the topic, ‘Ouroboros’. But Sandford is no mere provocateur: the highly accomplished artist has exhibited far beyond my feed, at prestigious institutions including the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit and the Centre de la Photographie, Geneva. He even features in Sir Elton John’s Photography Collection. In speaking with the Sheffield-born, LA-living creative, it’s clear he cites this discord of location, medium and canonization within everything he does; striking Freudian chords alongside mythological references and 21st-century anomalies. His speciality is holding up a non-judgemental mirror, standing back, and revelling in the cognitive dissonance of it all – something he continues to do throughout our conversation. With his new book, The best way to learn a foreign language is in bed, hitting pre-orders this May, GLAMCULT delves into the work’s global portraiture and the intimacies behind the explorative spaces in which men have sex with men.

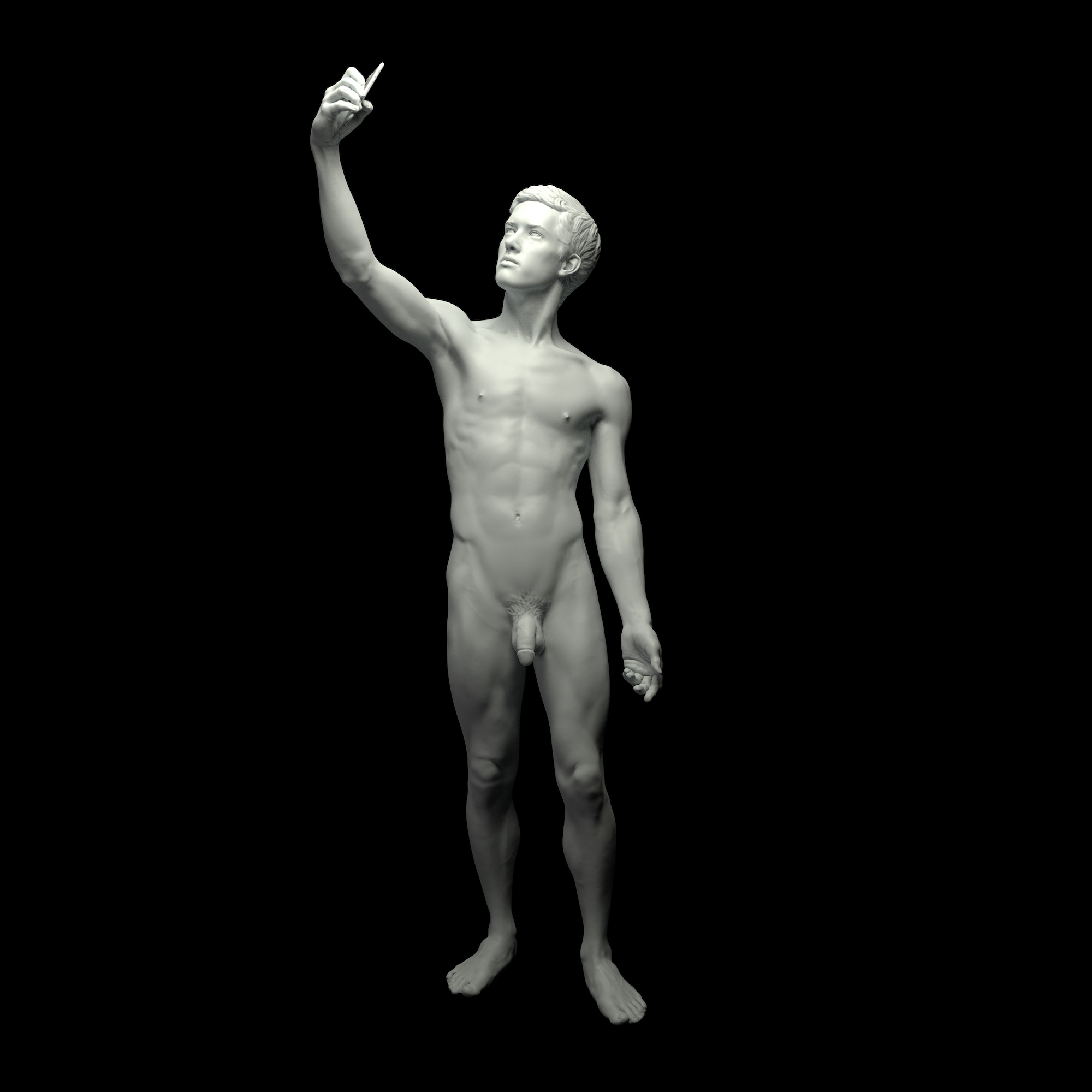

Selfie (Sean Ford), 2020

Selfie (Sean Ford), 2020

“Oh, there’s definitely a docu-style present within my work, especially through photography – I’ve always called these my diaristic portraits,” Sandford remarks when asked about his role as an observer.

And indeed, it is this notion of a ‘diaristic portrait’ that makes his work so profound. Effortlessly capturing a person’s societal mask, he runs it through his own optic and turns it back around to the individual like an all-encompassing prophecy. “I’m not interested in the technical aspects of photography,” he explains. “I learned them and abandoned them. I want to put all my attention on the subject in front of me.” He is earnest about creating this intimate environment, a relationship between him, his subject, and the third reality – something particularly present in his Polaroid Series as well as CUM FACES. “Self-knowledge and awareness are the key,” he declares. “We need to embrace all aspects of ourselves and our vulnerabilities, our strengths and weaknesses. It’s only when we know ourselves fully that we can strive to be the people we really want to be.” There’s something conspicuously Plato’s Cave about it all – an allegory long overdue its 21st-century makeover.

The Sluggard (After Leighton)

2014

The Sluggard (After Leighton)

2014

This quest for interconnectivity between photographer and subject comes from Sanford’s dedication to achieving artistic liberation, he explains: “I always wanted to celebrate my sexuality and put the male nude body front and centre in my work. I grew up with negative depictions of LGBTQ life within popular media and thought it was important to depict the opposite – so portraying male intimacy became a natural focus.” It is within these private moments that we see a vulnerability – hard to capture, but when successful, it transports the viewer to the realm of greats such as Nan Goldin, Ryan McGinley and, inevitably, Martin Parr.

“These moments are usually private, but there’s a long tradition of queer artists putting their lives, faces and bodies on show,” Sandford explains. It’s a tradition that, within our cultural climate, should be both praised and appreciated as we continue to learn from other people’s willingness to showcase and educate. “It’s a mixture of social documentary but also curated or repeated moments that could be fantasy or reality,” Sandford concludes.

That fantasy, however, is ever becoming a reality, which for Sanford was catalysed by his move to the US: “My work has been embraced much more here, especially in Los Angeles where I’ve spent the last five, almost six years.” Why, we wonder? “The UK is still very traditional and stuffy in terms of what’s acceptable as ‘art’ and what isn’t,” Sanford postulates. “Whereas, potentially because of the proliferation of the image, that isn’t even a question in LA.” In finding a home across the Atlantic he sought friendship and love – and set about portraying them through his work. “Throw in death and money and you have the full gamut,” he jokes. “Art is a search for truth and meaning within a chaotic – sometimes terrifying, sometimes beautiful – life that, at the end of the day, can feel meaningless. Love and friendship, and to a lesser extent sex, are the things that give life meaning.” After all, what is life without all the above?

These pillars, though far from new, gain a newfound relevance through what Sandford chooses to do with them, unifying them to 21st-century modes of living. “Within my sculptural practice, references to the modern day began with Sebastian (2012-TBA), which is heavily inspired by Antinous, the real-life lover of emperor Hadrian and considered to be the most beautiful boy who ever lived.” He is – of course – referencing the eight-foot-high stainless steel statue seen taking a selfie on a digital camera. “I’ve always referenced both classical and contemporary art history within my work, alongside pop culture,” he reiterates. “The selfie is fascinating because it’s nothing new. Artists and photographers have been making selfies or self-portraits since the beginning of making, as it’s the most accessible subject we have as artists.” It’s just now, however, that we are exposed to the mass-production and consumption of them, something leading to what Sandford refers to as the world’s obsession: “We’ve become obsessed with our own selves rather than looking out at others.” It seems that where once Greek Gods were the eye candy, it is now our own Facetuned masterpieces which send us into an emotive frenzy. “We live in an image-saturated world of social media likes and followers, with mostly unattainable ideas of beauty and wealth that are only available to the 1%, and it’s increasingly difficult for many to differentiate between those two realities.”

One of Sanford’s more recent pieces, ‘Ouroboros’, explores this phenomenon through an alternate lens: hyper-connectivity to our molecular beings. The sculpture, depicting a man and his just-out-of-reach appendage, is a symbolic jigsaw of life as Sandford sees it. “The piece reflects on the Egyptian symbol of the serpent (or dragon) devouring its own tale, but when we put that piece into a dialogue with my selfie collection, it adds another dimension: we’re all looking inwards rather than looking outwards to the world.” Finding our inner-selves may be the cliché haunting every aspect of our lives, but breaking this down into our fleeting connectivity, Sandford remarks: “In reaction to social media, we all know that, despite being hyper-connected every single second of every single day, we’re now more alone than we’ve ever been with both adults and kids today reporting that they have very few actual friends but many digital connections.” It is a social concern that continues to capture modern living, and especially within our current pandemic reality: the hunt for peace within our flesh-and-blood homes.

Adlocutio (Sean Ford) Statue, 2020-TBA

As with all art, meaning often lies in the eye of the beholder. Interpretation differs depending on the viewer’s point of reference – something which Sandford never fails to acknowledge. “Whilst there are differences to how my work can be read, from a (straight) male gaze to a female gaze to a queer gaze (which by their very nature are both subversive given that the majority of art we encounter is made by straight men), many of us have similar inherent ideas of sex and the self and our bodies, be those positive or negative ideas.” Creating work with a specified audience in mind is an idealistic interpretation of today’s mass-exposure. However, intention can be maintained through contemporary intellectualism and the rise of critical thinking as we redeem what Sandford describes as “sexuality rather than sex itself”. It is within this version of thinking that “the gaze can be considered similarly across genders and sexual backgrounds”.

All art strives to make social commentary, but it is Sandford’s willingness to receive the “what the fuck?” response that separates his work from that of the archetypal sculptor.

Cumfaces, 2007

Cumfaces, 2007

Cumfaces, 2007

Cumfaces, 2007