“Mine is a responsive, discursive position…”

Ed Atkins, moving-image artist, performer and poet, is one of the coolest representatives within the field of digital art. With characteristic dark humour, he critiques our fascination with virtual worlds by creating his own, using the digital body to remind us of our own physicality. Glamcult asked him about (not) being born in the digital era, CGI and magic.

It should come as no surprise that a digital artist prefers to do interviews by email rather than phone, face-to-face or even Skype. Despite the fact that most of his works feature talking heads—and even his own voice—Glamcult has not had the honour of actually seeing Ed Atkins talk about his work except in YouTube clips. Which is a shame—especially given that his answers are rascally, deadpan and, most of all, intriguing. Of his formative years—born in Oxford in 1982; grew up in a small village in North Oxfordshire; attended the local comprehensive school; moved to London for his undergraduate degree at Central Saint Martins; completed his MA in 2009 at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art—he insists there are no fun or noteworthy facts.

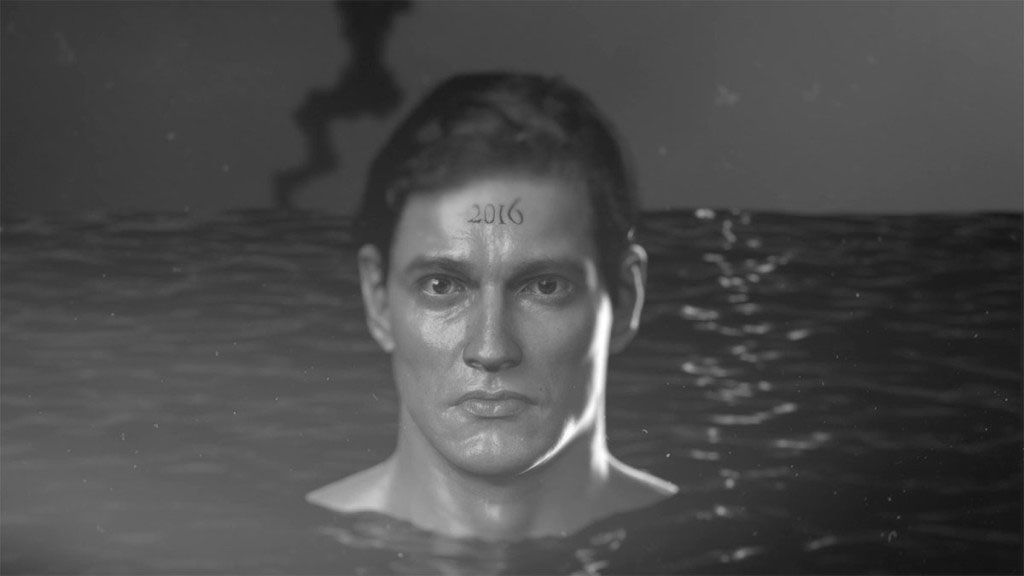

Using cutting-edge digital technologies in both production and display, Atkins is best known for his high-definition videos, surround soundtracking and digital compositing—rather than his drawings and collages, which are equally impressive and just as sinister as his digital works. But it wasn’t until 2012 “or so” that Atkins entered the field of computer-generated imagery as an artist: “I was struggling to work out what to point a camera at, what a photographic representation could possibly bring that was critical and new, to its subject. CGI eludes this problem: it’s generative. I can build from scratch, cleave very very close to discourse as the images generated never fall back into the imminence of reality but rather skirt it palpably,” he explains. In doing so, Atkins investigates the way we experience reality in a world that is becoming ever more virtual, addressing existential questions about how love, sex, death and relationships are experienced in a digitalized, disembodied world.

Widely considered one of the most authentic and factually one of the most talked-about artists of his generation, it is often said that Atkins is working on the artistic frontlines of the “digital native” generation. Atkins himself, however, being in his early thirties, rejects that descriptor: “I think I’m too old to be a digital native, so far as I understand the term: I wasn’t born into a world of computers and the internet.” But on a personal level at least, Atkins is far from mournful not be entirely at home at all fronts in the digital: “There’s a vast swathe of life and lives and the world that has nothing to do with any kind of digital. Insofar as ‘digital natives’ (and I don’t think the term has much of a proper grounding) might privilege the digital as the predominant condition, they might be pretty shit at coping with other things—things that happen when the power goes out.”

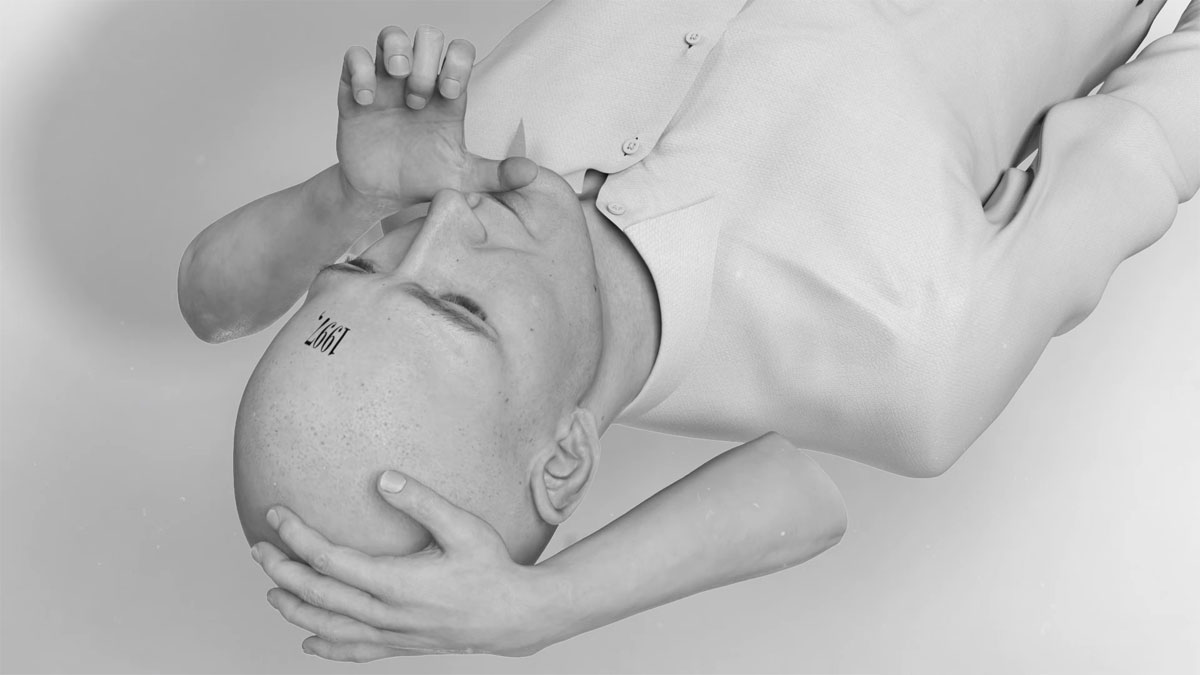

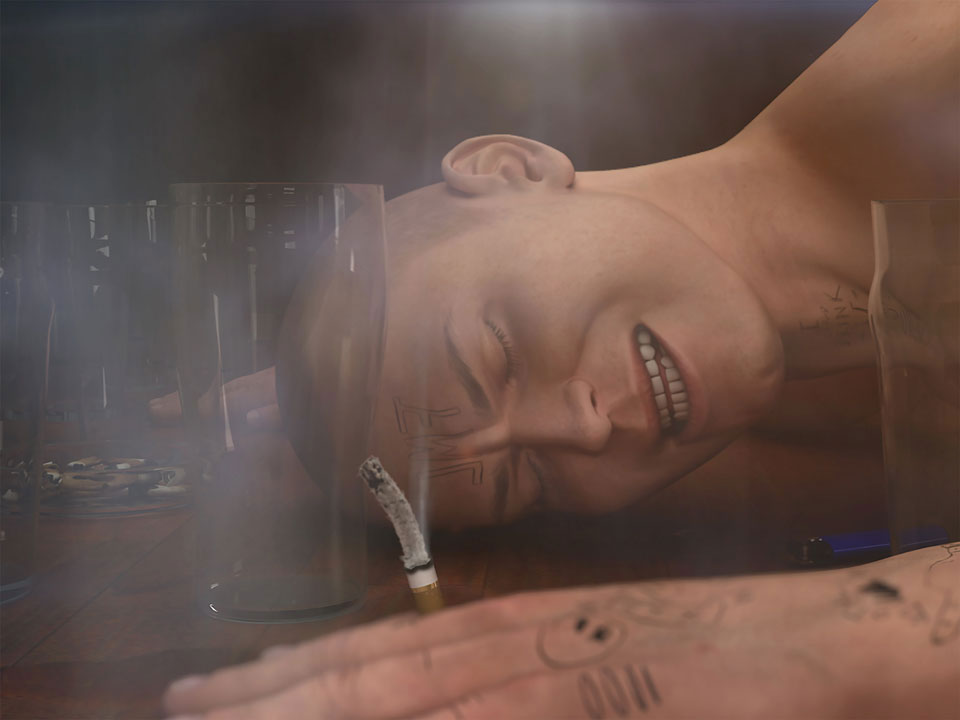

Atkins’ videos combine animated faces, body parts, animals, liquids—basically all the things that are most difficult to animate digitally—with repetitive fragments of spoken texts, poetry, music and rhythmic sound to create a grim fantasy world in which the body is a digital fantasy. Commenting on social networking and virtual societies, Atkins’ way of working connects with these worlds, in which we can play different versions of ourselves. Working predominantly on his laptop, Atkins builds avatars of himself, using his own voice and movements to animate his raw and emotional digital doppelgangers; the artist is literally acting in his videos. “I think of an expansion of the term ‘performance’, to include the processing power of a computer, the ways in which something succeeds at being ‘real’, at being convincing. In these terms, my videos pitch themselves.”

Atkins’ most remarkable CGI performance, No-one Is More ‘Work’ Than Me, lasted eight hours. “It was a little draining, but far easier that any other working day,” he quips. In it, the to-scale, shaved and tattooed 3D head makes a desperate bid for his own humanity. Observing a real-life person activating an avatar, witnessing a digital alter ego becoming a convincing person, makes the viewer all the more aware of his or her life in the physical world. And this is precisely Atkins’ intention when creating his hyper-real worlds inhabited by chain-smoking, alcohol-driven thugs, monkeys and disembodied hands.

Atkins’ newest cosmos can be entered this spring at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, which will present his first exhibition in the Netherlands, Recent Ouija. The museum’s ground-floor gallery will be transformed into an immersive environment of monumental operatic videos, collages and drawings. But what can we expect from the somewhat ominously titled Recent Ouija? “A chorus of works from the last two years, all of which speak to performance, representation, bodies and alienation. It’ll be a riot,” Atkins assures us. Of the title, he says: “I really like it! Ouija is a term for the board used, more or less jokily, to summon spirits, demons, whatever—who then communicate via a planchette that skates over letters, numbers and ‘Yes / No’. To me, it speaks of language, possession, occultism, symbolism, belief and genre: horror, a certain ambience and hauntings. Magic is a disease of language.” It’ll doubtlessly be just as deadpan cool as the original soul himself—or his dark avatars. But we’re wondering how this non-digital native thinks the digital world will develop. “I really don’t know. Mine is a responsive, discursive position—not prophesying or, indeed, particularly hopeful.” Just as we feared.

Words by Joline Platje

www.edatkins.co.uk

Notifications