Visualising a better future

Arca, Nonbinary, 2020

When visualizing a better future—one that contains neither a fear of technology nor of what society will produce from it—resisting the temptation to bite the apple is near impossible. Frederik Heyman has spent his whole career envisioning such a world. The 3D artist, whose work intersects the disciplines of art, fashion, music and culture, has drawn curious eyes since the very beginning. Having worked with some of the most seminal creatives of our time (think: Y/PROJECT’s Glenn Martens, Burberry, Thierry Mugler, Michèle Lamy, ARCA and Lady Gaga, among others), Heyman has established himself as a go-to collaborator in the digital sphere. We first encountered him back in 2011, and there’s an inescapable air of nostalgia as we feature the renowned artist once again. Join us in musing over a brave new world…

Ceremonial Formality, 2020

Does your work simulating an alternate world or a more critically aware version of the one we already live in?

I’ve never been interested in actively depicting a present or future vision, nor being a strong critic of our society. I’m more interested in a rearrangement of our reality, through a filter of observation via fantasies and desires—into what I call ‘a speculative present’. A photo-real or virtual suggestion towards an altered dimension. What I like about 3D scanning and digital alterations is that I can literally copy elements from our present world and paste them into this alternative reality. This reality depicts a detailed narrative that I’ve created out of the desire to overcome humanity. This doesn’t mean it has to be sci-fi, or a robotised representation of the human body; rather, it’s an exploration of the human body under the influence of, and in interaction with, technology.

Your work, though beautiful, seems designed to invoke distress in the viewer. Where does this come from?

I don’t intentionally want to invoke distress, or offend—though I often get that feedback, which is a sort of twisted compliment. It’s a strong emotion, which makes you respond. Whether the spectator likes it or not, it makes you question. I don’t see the use in creating imagery just for the sake of pleasing the eye. It can only survive through strong statements and vision.

Though the message behind each piece differs, there seems to be a common narrative to your work. How would you articulate this?

That’s a good question. I ask myself this on a daily basis, which speaks to the core of my practice. It’s an internal research project that perpetually goes on. In general, I’m interested in the trans-human approach of how life and memories are preserved, and henceforth pursued. The decay of the human body and the desire to overcome humanity. How this affects our body and desires… the emotional side.

Y/Project accessories campaign, 2019

Y/Project accessories campaign, 2019

High fashion is integrated within most (if not all) of your pieces. Why do you think the fashion world gels so well with yours?

We live in a visually oversaturated world. Our sensory input is reaching a climax. Everyone is screaming very loud to stand out in this climate. I think the advertising world is always looking for new, appealing media to reach its audience. The virtual world—now even more so with the pandemic—is a new, attractive platform with endless possibilities to reach people and spread their message. I feel many clients want to explore this. However, I do feel slightly reluctant. I strongly believe the digital world needs to be used for its purpose as an alternative reality and not as a marketing strategy. My work is graphic, streamlined and highly detailed, which goes

hand-in-hand with the representation of fashion. I love to work with fashion houses, as long as we elevate one another. Creating a visual is a merging of many factors, and fashion is one of them.

The work you did for Y/PROJECT was truly dystopian…

I didn’t intend to make the disconnected body parts look like a freak show, but more of an abstraction of essential, performative body parts, one which the accessories are presented in. Eliminate what isn’t required for the act…

Within this you create a level of almost purity—purity through elimination—which is particularly gripping within the narrative of sexuality.

When starting a dialogue with an artist, I love to dive into their world, get a grip on their inspiration and story. From there on I start to build a world. Glenn Martens from Y/PROJECT said the main inspiration for the collection came from the Kamasutra. I was already playing with the idea of making large-scale abstract mechanised love scenes. This fitted perfectly with the subject of the collection. I created two main scenes, in which clouds of mechanised bodies are sexually interacting with each other (without making it too explicit).

Dust Magazine issue #13, 2018

This creates a kind of external illusion—one with an almost higher power.

Yes. I wanted to add an extra layer by having an external character in each scene that seems to guide the movement of the bodies with a controller, presenting it as his/her/their desire or fantasy being performed. I balanced the cold mechanics by adding nature, a fertile environment.

Within this illusion you’re creating ‘alternate beauty,’ right? This is especially present in the Gentle Monster series—or is it more a reflection on the rising freedom of beauty?

Beauty is obviously a relative subject, and I believe the new generation perceives beauty from a much wider spectrum of references. Mainstream beauty standards aren’t the same as a few decades ago. With the rise of social media (sub)cultures blend, visual boundaries fade and people are now in charge of choosing their own framework to draw references from. Here, the very definition of beauty is redefined.

Do you consider your work to be beautiful?

I don’t consider my work as beautiful. That’s just one simplistic layer on the outside, a shallow coating. We’re living in exciting times, where brands are starting to think outside the box. It’s no longer about just a simple, beautiful image; it’s the bigger story—the artist, the story and the scenes, who the model/performer is and what story they bring to the table…

Ceremonial Formality, 2020

It feels as though there’s a true integration of who you are as well as the energy the artist brings in your work. How do you go about creating these collaborative visions?

When collaborating with other artists, finding a merge, a beautiful fusion of different worlds that blend together in a new language is the most important thing. Usually, I start by creating a rough blueprint for the project, a Google Doc in which all ideas are imported: no limits, no restrictions. I love to make diagrams, connect, freely associate and overlap ideas together, with the collaborator. In the next stage, I make detailed sketches of the set-ups, a storyboard. This isn’t always an easy process, as they are shaped organically in my head most of the time as what makes sense to me isn’t always understandable for another person. Then, the production lifts off and we start with the 3D scanning or filming. I build a digital world around the characters. I love to get lost in details. Nothing is left to chance.

This detail and sense of fusion was certainly clear within the ARCA piece as Botticelli’s Venus!

Working with Arca was very wonderful, we had a unique artistic and intellectual connection on the approach of the imagery, one that I deeply cherish.

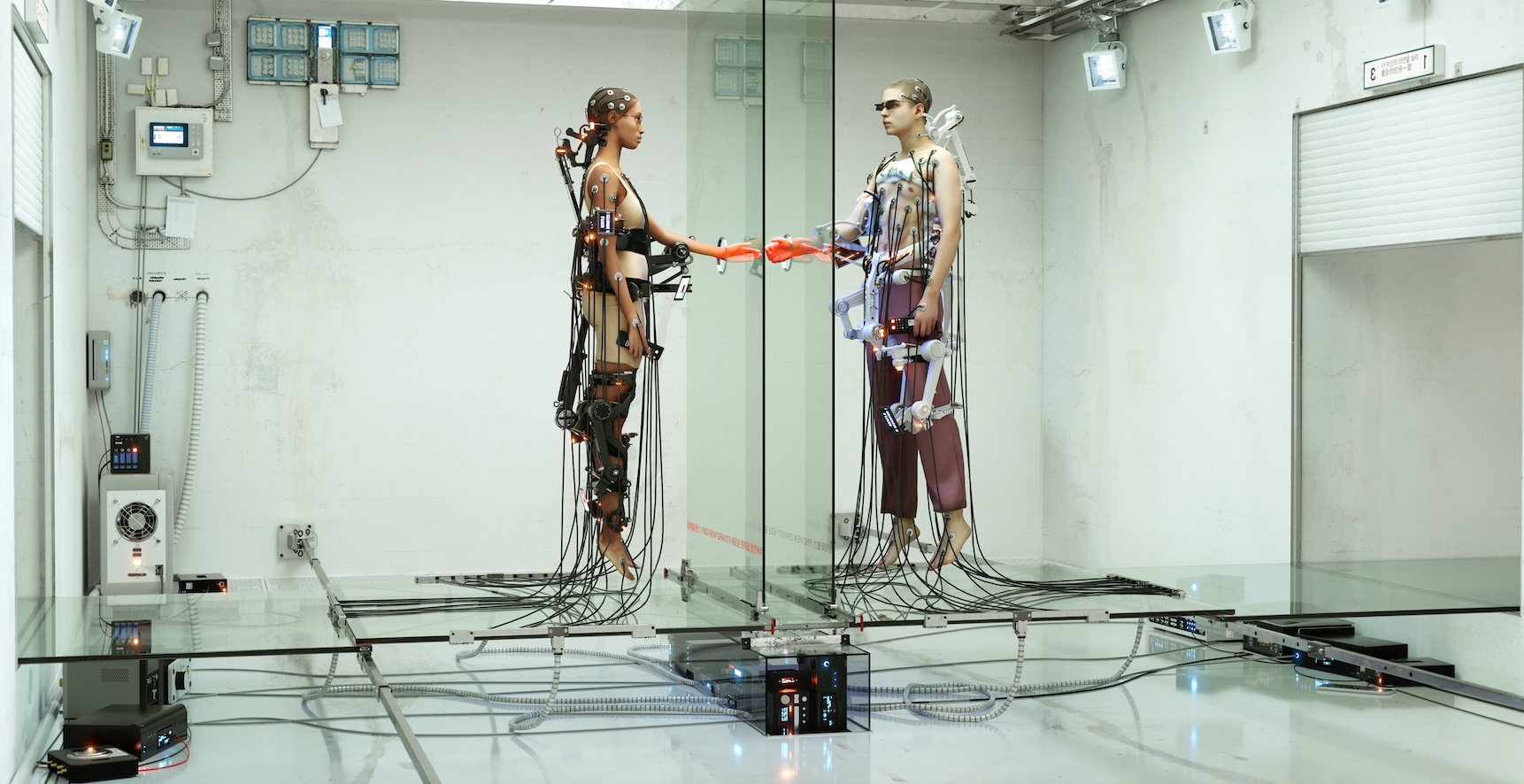

Alongside the human form, the industrial and technological take centre stage in your work. Do you find these aspects are becoming synonymous these days?

The human body and the technology we have in today’s society are growing inevitably towards each other. The human body gets enhanced and extended by technology, and vice versa: technology is inspired by the organic world. They complement each other. We’re already in the middle of it, without very well realising it. The next evolutionary step of mankind. It doesn’t have to be a scary dystopian scene from a blockbuster, but a bionic upgrade of nature’s masterpiece, reaching our full potential and hopefully exceeding far beyond this.

How does this human-to-technological interaction manifest?

In my work, I’m intrigued by the human body under the influence of these mechanics. The enhancements, alterations and interactions with it.

Arca, Nonbinary, 2020

Gentle Monster eyewear campaign, 2019

This influence speaks to the notion of a higher power, right?

I see a surrender to an external control, a higher force—or, rather, humans taking control via mechanics to reach an emotional state of empowerment. It almost becomes religious.

The DUST series honestly blew my mind. Could you tell me about the intention behind the Salomon piece in particular?

DUST was crazy. I still can’t believe we pulled that off! I think I was on a creative high during this period. Each scene was a portrait of a Belgian artist/creative, up-and-coming or established. The creative team from DUST and myself drew some loose references from cinema and art history. The Salomon piece was based on BDSM, the power [gained] through surrender. The male bodies, in the action of being suspended, in separate booths next to each other. The booths can be read as a sequence, a progression of a love story from left to right. The suggestion of voyeurism in the background where the eye peeks through the wall, a suppressed sexual desire. I wanted to introduce the softness of the male romance in contrast with the ropes and chains.

Your references are always so striking, particularly when you refer back to iconic moments within art.

I never hide the references. Like with the Inge Grognard piece, we did a retake of a scene of the iconic work of Pasolini. When reworking iconic pieces, I do a contemporary take on them, creating a tribute or homage.

I fell in love with the Glenn Martens piece because of this contemporary take. Revisiting it in 2020, it felt like a commentary on societal imprisonment.

Glenn Martens wanted to enter into dialogue with himself multiple times (and of course, dressed in Y/ PROJECT). Each Glenn has a mirrored copy of him on the other side. They aren’t speaking, but non-verbally staring at each other. In between there is a glass layer with a hand-written text on it referring to time. “Time continues to pass. Night turning to day…” The bodies are locked together by the knees, a confrontation that can’t be avoided or escaped. The almost prophetic social distancing element is a funny side note indeed. The feet are submerged in an elevated pool filled with an oily liquid, connecting all the bodies.

Gentle Monster eyewear campaign, 2019

Similarly, the piece Ceremonial Formality had this feeling of entrapment but within a factory-based system.

I created Ceremonial Formality for SHOWstudio. I wanted to create ceremonial settings in domestic environments. Living altars, with performers centre stage. The elevated altars refer to the divine status of the post-human body. A mechanised incense system attached on the table. I wanted the performers to explore the limits of the human body. This can easily be done in CGI; you can position a virtual model in any pose you want. But I wanted to 3D-scan the rawness of the real human body in action. We worked with a contortionist who was cast for her specific poses she performs. In this shot you mention, she was balancing her whole body weight on her mouth piece. I love the oral focus, and connected it to the spectator next to the table on the chair. A personal, intimate oral connection between them via air flow. I digitally added the bendable cage, following the dynamic outline of her body. More like a caged armour. I too ask myself, “Is she locked in, or is she in charge and steering the ritual?” The soundscape includes a metallic voiceover, saying: “Transcending the limitations of our natural condition,” and, “A consciousness untethered to any physical thing.”

How does such an abstract concept come to life?

These images grow organically in my head. I do love to have a starting point to set a base from, but then add layer upon layer towards a bigger story. “Less is more” was never my thing, even though I try sometimes. As a student, I studied to be an illustrator before studying photography. I feel my creative process still goes back to how I approached images back then.

In today’s rapidly changing world, where do you hope the RISE to change will take us?

A drastic change in thinking, being in charge of your own story and deciding what you take in; no longer being guided by established patterns. People are still too easily offended by whatever is deviating from their path, and that is predetermined in our outdated systems.

…And if this change is reached, where do you hope to be in the new world?

Still creating. I hope new media will arise. I want to explore many more things … with my husband and my dog. They keep me sane and grounded.

Dust Magazine issue #13, 2018

Photography by Frederik Heymans

Words by Grace Powell