About Respublika, his utopian world crafted at Holland festival

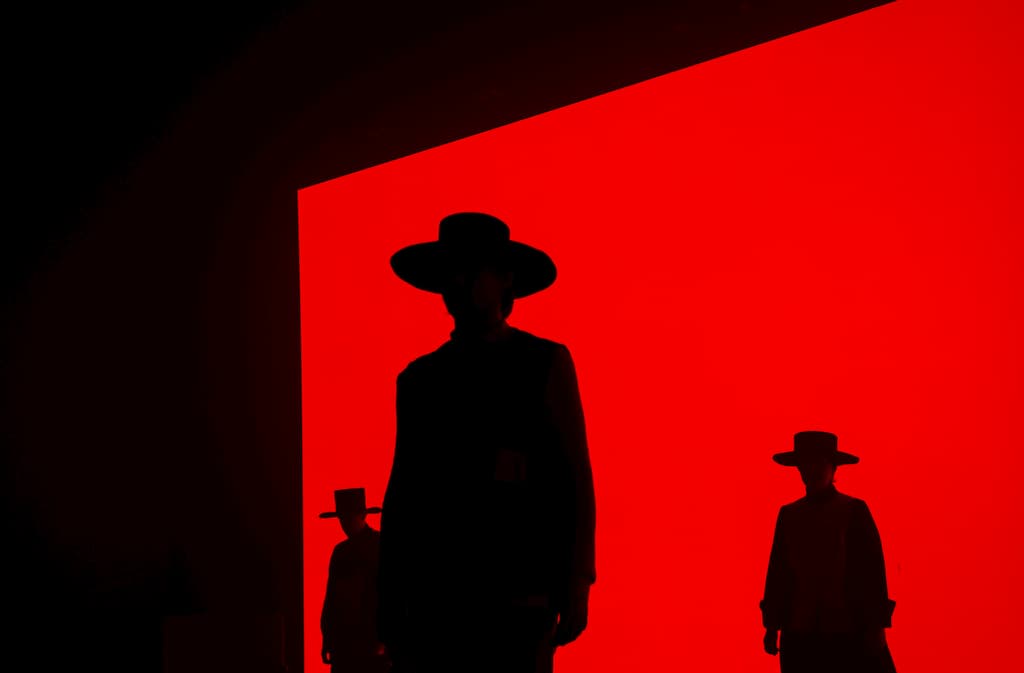

At the crossroads of film, rave, visual arts, and theatre lies a sweet spot where Lukasz Twarkowski establishes his own alternate world – and we are invited to join. His performance for Holland festival takes us to the Lithuanian woods to follow a journey of a community that abandons their mundane concerns to find refuge in living together and surrendering to dance. In a space where it’s allowed to indulge in the “unproductive”, the audience is welcomed to follow the internal conflicts and desires that start to bubble up once the weight of efficiency and performance is taken off. Towards the end, spectators become a part of the show, merging with the theatrical stage as it morphs into a dancefloor. Respublika is a utopian, yet not sugar-coated, exploration of what could be – it doesn’t aim to teach, but rather to immerse and question. Eager to learn more, we caught up with the mind behind it to talk about everything from his inspirations, to the rise of mockumentaries, and rave as a political act.

Hey, great to speak to you! How are you today?

I’d say it’s a perfect day so far. I’m in Greece with my friends and co-creators, working on an upcoming project.

What else can you ask for? Don’t want to take you away from the sun, so let’s get right to it. Tell me – how did Respublika come to life?

I was a very long preparatory process – the idea was completely crazy. The beginning of it stemmed from a real Republic, Republic of Paulava, which existed not far from Vilnius at the end of the 18th century. It was created by a Polish priest, who bought land with 800 peasants. They created an independent state which had its own army, money, some kind of healthcare system, a theatre, schools, etc. It was known as the peasant’s paradise. In the end, it wasn’t that perfect socialist state they promised, but it inspired us to search for that moment when you can really feel free in today’s world. Somehow, for me, it instantaneously connected to rave and creating temporary autonomous zones – probably the only possible zones full of complete freedom. The next question was about what would the next biggest social change be. The first answer that we found was related to labour and work, and that we have to face the idea of basic income if we want to continue living in some kind of harmony. So, these concepts were at the beginning of this experiment – because we started it as one. We left with all creators and actors to the woods, trying to see what it would be like if we didn’t need to work or to perform. It was complete freedom.

Peasant’s paradise indeed. How did this manifest in the performance?

From our side, we were trying to give everyone the spark of the raving culture as we know it – we were showing them a lot of movies about raving, teaching how to DJ, how to build up the new place. And pretty soon it became kind of a rule that we were supposed to do a new rave every single day. In my mind, I had the idea of what the storyline of the performance would be – one that speaks about the society who spent whole year in the woods, trying to check out the basic income idea, but with every week, they became more and more possessed by electronic music and dance. That’s what they finally do: they start raving every single day. And after that year, they decided it was kind of a failure because they didn’t find any social answers that they were searching for. They just had a very good time. They then split up and go back to their ‘normal’ lives. Eventually, after 5 years their reality becomes so unbearable that they decide to reunite again – they realise that what they experienced during this one year of raving may be the only answer. We wanted to create this experience for the audience. Being together and dancing together may be absurd, but at the same time, finding this deep emotional connection is the most valuable thing that we can do right now.

I love the circularity of it. Would you say that freedom is always bound to be temporary, then?

We very quickly realised that our simple experiment on basic income is absolutely nothing compared to the complexity of all the overarching systems. We’re living in times where we are unable to understand what is really going on. And everything is tempered with in every area. Take raving culture – it’s being so heavily commercialised. At the heart of it, raving is inherently anti-capitalistic – it’s built on pleasure, togetherness and community. That’s why it used to be so under the radar, and why governments were fighting against it so heavily. You can see it throughout the history of rave and how it was being banned as it travelled from the UK to France to Italy…

Rave is central to your work, but Respublika is also a theatrical piece. How do you nurture these two elements and how do they interact within your work?

I can’t spoil too much about it, but I would say that it is divided in three parts. The first part re-enacts the architecture of some places from the past, which is being transplanted from the Lithuanian woods to Amsterdam this time. Then, there is a more narration-focused part. We use live montage and double channel video, so it’s possible to follow the performance in two ways – you can watch it completely as a movie, or be a part of the events. A lot of material was shot in the woods. We first went in the summer, which was really fun. In winter, temperatures would go below zero, which made it so hard to film and enjoy ourselves. It was harsh and wet. The third part is where all acting is slowly stopping, and we transition to a rave.

Looking at the stills, you create a very strong post-Soviet atmosphere, like the scene at the table. Is that a conscious choice?

Of course, we were taking inspiration from the place itself, given that so much of the foundation of this project is connected with Lithuanian soil. A lot of elements, like the sauna, were already there at the place where we were staying, so it was also about embracing the architecture we were placed in. At the same time, when it came to casting, we really wanted to portray this very heterogenous group to capture something more universal than just a generational experience. The youngest actress we had was around 28 years old, and the oldest one was over 70! We also wanted to mix, for example, more Berlin-style contemporary youngsters with older Slavic characters with a more post-Soviet style. And we’re so happy that it works. I think it’s so uniting – you have generations that revelled in the dream about freedom in the past, and are now trying to do it again, and then you have young people who have their journey ahead. Seeing people with an age difference of over 50 years, and all ages in between, dancing together united by the same collective freedom is the most beautiful experience to me.

The show has also been described as a mockumentary. Talk me through that notion…

I am really amazed by the development of mockumentary narrations, and I believe they are very symptomatic for nowadays. We’re in contact with hyperreality so much, that the lines are getting so blurred. In the mockumentary format, which is renegotiating the border between the real and fiction, there is some kind of very interesting tension, because you never know what really happened. Somehow it simultaneously has the form of documentary, but it’s not fully true. It makes it much more interesting – it’s like an imaginary adventure that you’re having being a part of these events. It reminds me of Simulacra and Simulation by Baudrillard, where he’s writing about Disneyland, which is needed to show that there is something less real than american life. You need to have some kind of a less real point of reference to prove that your unreal life is actually real. I feel that there is like something similar in this philosophy of mockumentary. Somehow, we believe that documentary movies tell the truth, where in fact, they can be much farther from the what we would call the truth than any fictional form.

At the same time, it feels like you’re building a utopia. So, would you say that we shouldn’t look for answers within your piece, but rather see it as more of like a thought experiment?

Yeah, we’d never provide any answers. We’re very bad at providing answers because we never searched for them. We are usually trying to test different phenomena and watch from close. I thought I came up with it, but I recently found out that it’s actually Francis Bacon’s words: “If you can talk about it, why paint it?”. So, this is how we work – we’re trying to build up a multi-sensorial experience that is impossible to grasp with words and one that is not looking for answers.

Respublika sounds like a very monumental name, but also strongly political. What does it mean to you personally?

Well, it first came from Republic of Paulava, which is the inspiration from the beginning. We wanted to show it rather as an anti-political movement, as during the show you see that they quit political issues and instead they start to work on emotions. We wanted to keep the name with political connotations that also becomes some kind of a trademark – this is Respublika, and it might as well be a name of a band or a DJ collective.

In a true mockumentary style! And my final question is, what are some of your hopes for the future for yourself and for the world?

I can go on forever! Coming from a country like Poland, we are now in the centre of the far right. I just hope that this nightmare is going to finish one day. This goes for the rest of Europe, too, as we can see the rise of the far right pretty much everywhere. In these times, it’s pretty hard to have positive kind of dreams – it’s rather hoping for the nightmare to finish. When the war in Ukraine started, and we were playing Respublika for the second or the third time, it was the question of shall we even do it. It felt wrong to rave during wartime, but then we understood that it’s a form of standing up as well. And I know that we have to keep on creating our own pleasure and joy that they’re trying to take away from us. The first goal of oppression is to castrate you from happiness and any hope that can come from it.

Within that, do you view art as a form of resistance?

Of course, but what is political is happening on many, many levels – it doesn’t have to be openly political to be political. I want to believe that Respublika itself is a deeply political act as well. However, I’m kind of pessimistic – I have a feeling that culture has somehow less and less resonance. Maybe it’s connected to my last years in Poland, where we see how many protests and strikes don’t do anything, and how culture is being killed by the far-right government. At the same time, as artists, we have to alert, we have to speak, we have to shout – and I know I will continue doing that.

On show June 22 – 23, 2023

Afterparty by RadioRadio (both days)

39 & under? Visit Respublika with HF Young discount

Get your tickets here!

Check out the full programme

Words by Evita Shrestha