The artist talks queerness, literature, visibility and his new show at Foam Amsterdam.

There is something so raw and honest yet deeply perplexing about Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s work that it quite literally electrifies you. From the moment I enter Foam a day before his Double Enclosure exhibition opens to the public, I sense an invigorating excitement in the air. Foam curator Mirjam Kooiman and I are having a chat over tea about the instant connection she felt with his work when she first saw it shown in NYC a while back, and as she informs me on details around her work on curating Paul’s first solo exhibition in Europe, I can’t help but notice the flame and spark in her eyes as she talks about the artist’s work. Highly abstracted yet personal, Paul Mpagi Sepuya turns traditional portraiture on its head through ingenious and fragmented compositions of subjects, the studio, his camera and mirror, and himself. The artist plays a self-assured game of exposure and concealment, lens and mirror, enthusing a dialogue between identity, sexuality, desire and longing. Eager to know more, Glamcult sat down with Paul for a casual talk on not-so-casual matters.

Mirror Study, 2016, Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Your first solo exhibition in Europe! What’s going through your mind?

It’s really exciting and it’s been such a great experience working with Foam’s team. It’s an interesting experience to do a project like this one that brings together works made over a period of time as opposed to making work for a show. Normally, you spend so much time on projects, thinking if they make sense to you as an artist, while with this exhibition it’s also about someone else’s angle and view on it. It’s not about editing work that is yet to be seen, but working with things that are already there to bring together a concise proposition.

You were born in California, but you’ve been moving quite a bit between LA and NYC. Does the place where you find yourself living at a certain moment in time influence your work or style in any way?

I once had a curator telling me that they’re opening a space in Malibu, or somewhere, and that were looking for ‘California-looking’ things. I was like, There’s nothing I make that looks like California, or like anywhere else for that matter. Visually and stylistically, there’s nothing of the city that I’m in that you can trace in my work. If you know the people in the image, you may be able to say, Oh, these are people I know from a certain scene in New York, for instance. If anything, the portraits are about making sense of a lot of emergent friendships and relationships that were made in spaces, which are unique to New York’s social and spatial structure. A lot of the context for understanding the work relies on recognition—on a subway platform, catching a glimpse of someone whom you might recognize from that 4 AM moment in the club.

Study for an Exchange, J.O. with Four Figures (2203), 2015, © Paul Mpagi Sepuya

So, in a way, not the physical city itsself but rather the way of fragmented living in that particular environment?

Yes, and that does play in some of the current work that’s fragmented. But that’s not where the fragmentation comes from or what it’s all about. Sometimes it can be read that way, but it’s more about me having my first studio after moving back to LA in 2009. I was able to have a space that could accumulate unfinished material and fragments of things—test prints, notebooks, things I was reading or an object that a friend brought to the studio and left behind. What does it mean to make work in a space that changes constantly? For the work in this particular show, the fragmentation started with me trying to use the studio as a recurrent backdrop, which gradually transforms yet holds on to information. I’d layer prints on the wall, forming unformal collages, and also blow up and crop things to then reconstitute elements relating to a person or space by pulling parts together on the mirror sufrace. Then I’d photograph myself through the gaps within those fragmented parts—not with the intention to further hide or obscure, but to bring something I had related to, that was dispersed throughout all that material, to one whole piece again.

This makes me think of your outspoken interest in literature, especially Richard Bruce Nugent and the significance his modernist, stream-of-consciousness style has for your own work. And when I look at your photographs, I do sense a stream of images within images within images. In what ways has literature informed your work?

I think there’s just lack of good writing in the photography medium that’s on portraiture for the sake of portraiture. Of course, there’s lots of great stuff on documentary or activist portraiture, but not on why we take portraits as a way of understanding ourselves. I was frustrated by that lack. So, I found better writing on portraiture in and through literature, particularly queer modernist writing—from Woolf to Baldwin and Capote.

Draping (1_959639), 2016, © Paul Mpagi Sepuya

On the topic of portraiture, I know you’re interested in exploring the dynamic between the conditions of making a portrait and the content depicted. Can you tell me more?

One thing is the fact that I don’t photograph models or people that I don’t know. It always needs to build off of something. I have friends whom I’ve photographed continously over different projects for more than thirteen years now. So, each portrait will respond to what was happening at a particular moment in the studio but it’ll also play off of previous images. There’s two images in this exhibition that are a back and forth collaboration with a friend of mine who’s a writer. One is an image alongside a cover I did for him, and the other is something I assembled from a correspondence with him in which I’d send him pictures of him sending me pictures. There’s also an image with another friend of mine—a portrait in the darkroom in front of a mirror, with him standing behind of me. But the conditions preceding this are the extensive collaborations we’ve had. You can look at the work and bring any interpretation you want to it, but it’s all gossip and things an academic can never put in writing. I’m interested in making pictures that are formally strong and can stand for themselves, but in order to actually understand the work, you have to set aside medium or discipline-specific things and go to the bucket of stuff that you don’t know what to do with.

Mirror Study, (OX5A1317), 2017 © Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Another thing that intrigues me is how your portraits relate to selfie culture, where capturing your best, entire self is seen as necessary for a perfect outcome. You somehow capture less yet reveal more?

I still make very straightforward portraits—it’s where and how it all starts. There’s no one who appears in my works as partially concealed that is also not fully revealed somewhere else. Also, constructing backdrops and using drapery in my photographs has been an exploration of delineation of the spaces that are meant to be seen as contrasted to those whose implication is to remain hidden, with me moving the subject between those spaces. It’s kind of where you choose to look as well.

This makes me think of queer identity and the queer body that your images construct too. Am I right in thinking that your art is, so to say, a free and wilful example of queer identity liberated from the expectancy of being boxed and defined. In a way, with queerness, there’s more patchwork that goes into building an identity.

Well, the collage aspect is less about assembling a queer body or identity, so to speak. It’s more about each element of the fragments or the backdrop trying to work out the language of a photographer’s darkroom, where work is developed in complete darkness, for if brought to light, it’ll be destroyed. How do we connect this to the history of non-white spaces, literally in the back of a bar, for example, where queer folks can hang out? I was thinking about the social encounters happening in the dark that have to be negotioated in the light at the front. Also, those moments when you encounter someone or you get a glimpse of something, and you think, Do I know this fragment of a body from this other experience? Here again, the dynamic between the conditions of making a portrait and its content plays off, but also the information that is left as traces here and there, like fingerprints on the mirror in some of my images—the type of information that literally requires a body so that blackness can be seen, and what that suggests.

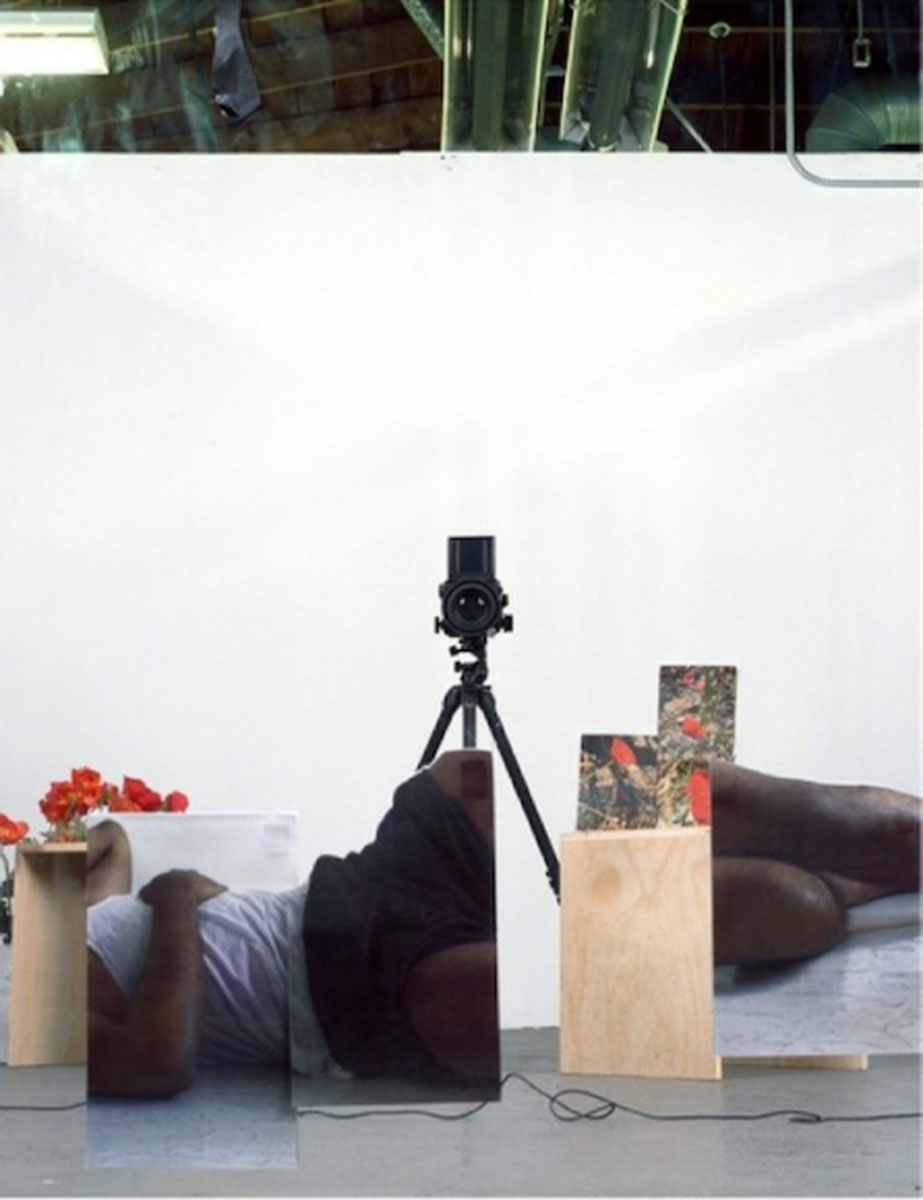

Figure with poppies after RBN (2604), 2015, © Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Speaking of the queer body, the presence of the camera in some of your image as a subject also adds a queerness and uncanniness to the image.

The camera is placed at the centre of the images, because they’re not supposed to be tricks. The camera adds honesty, making the image give itself away. The photographs are not pretending to be something that they’re not, and it’s important that their physical construction is made visible. I want you to look at the camera that’s making that image, and if you spend enough time looking at it, everything that’s there reveals everything about itself. And that’s why the mirror is also not clean—I could have easily removed all the finger traces and the smudge someone’s arm had left. Yet, I wanted, as you looked at it, for the space to not disappear into nothingness and for it to also be a loop that reflects where you, as a viewer, want to position yourself.

It is also a stripped down, raw and minimalist queerness that you portray. What are the roots for this stylistic choice of yours?

Yes, when I take portraits of people, I’d always tell them to wear the most simple, plain thing. I don’t want them to be contemporary looking, or historically looking. Once you strip everything down, or simply wear jeans and a t-shirt, it just all easily falls out—whatever that may be.

We’ve talked heavy stuff for an hour, I do want us to finish off on a lighthearted note. You don’t photograph strangers, but what’s a figure from history you’d love to do a portrait of?

Well, maybe I’d like to think I can be friends with someone from history. Could be Virginia Woolf, could be Richard Bruce Nugent. I can pull so many different figures in, I think any of them I’d love to make a portrait of…

Mirror Study (Self Portrait) (Q5A2059), 2015 © Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Double Enclosure

14 September – 18 November

Foam Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam

Words by Valkan Dechev

All photos courtesy of Paul Mpagi Sepuya

www.paulsepuya.com

Notifications