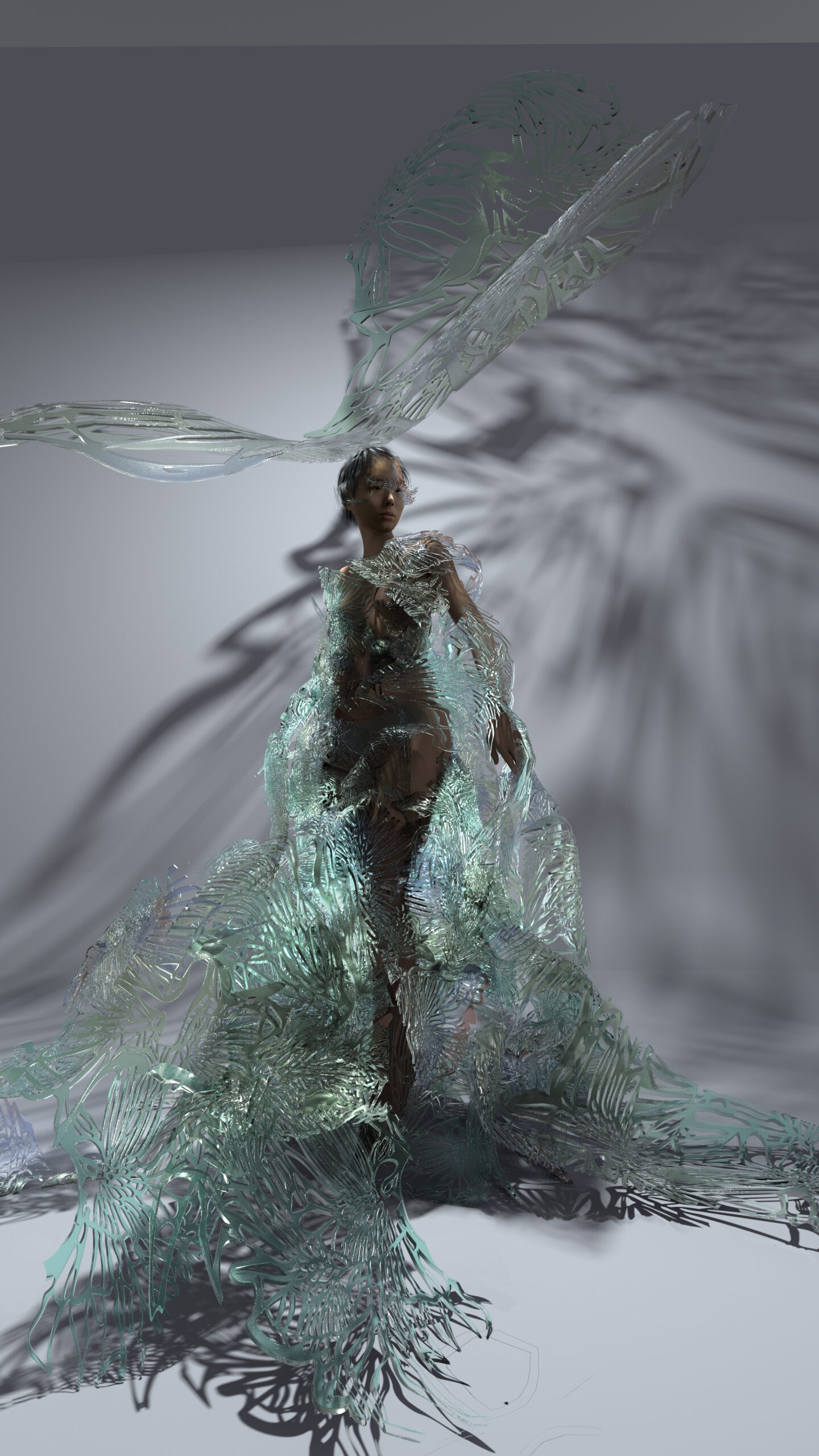

Decomposition of materialities and identities

Scarlett Yang gives us a glimpse into the future, where nature, art and technology all co-exist in harmony. From big fashion houses to car industry giants and bio labs, Yang has done it all. Incorporating her extensive expertise from all things fashion, design and technology, Yang’s practice epitomises innovation – both conceptual and material. Her work now lands at Tropenmuseum as part of Plastic Crush, an exhibition exploring the local and global influence of plastic, looking specifically at the relationship between humans and materials. The centrepiece – a completely biodegradable dress in ‘bio serpentine lace’, a glass-like medium created from algae extract and silk cocoon waste. Ethereal and elusive, Yang’s work is a study into the material and immaterial, in which natural forces come into play with design engineering – all visually stunning, of course. On display until May, the audience is invited to witness the dress disintegrate in front of their eyes, in all of its beauty and grace.

I was very excited to see your work at Plastic Crush! Could you talk me through how this opportunity came by?

It was basically connected by the New Order of Fashion organisation in Eindhoven. The curators of Tropenmuseum were looking for a wide range of artists, and we had quite a specific proposal to echo the theme of the exhibition.

They do feature a lot of artists from different disciplines across fashion, but you come from a very cross-disciplinary background. How does that help your artistic practice?

It’s definitely the key to my work. I do have a background in fashion from Central Saint Martins, design research from the Royal College of Arts and Design Engineering from Imperial College in the academic part, and also working across different disciplines all around, from bio labs to car industries. It allowed me to put on a different hat for each project, I would be able to jump across different roles. And also, to explore different questions, like how industrial design can help fashion to achieve a more circular supply chain through the optimisation of certain parts of that project. Or vice versa, with a 3D design I could also put on my visual design fashion hat. It also helps to communicate with other people within the team. It’s never a one-man job. I think that’s how the future of design will be.

It’s creating a discussion between different disciplines. ‘Plastic Crush’ engages in the conversation about the global history of plastic and how it impacts our daily lives. How is this dialogue important to you and your artistic practice?

I’ve been engaging with the theme of material circularity for quite a while now. I’ve experimented with biodegradable materials, recycled materials, digital fabrication, generative design, system-led thinking and so forth. I think for me, it’s just everything that revolves around striving to improve for the better.

It’s a central idea, not an additional thought.

It’s not additional for sure. Some of my projects involved collaborating with big brands and tech companies to find solutions and bringing their resources into my creative vision. I’m still exploring, it’s not an endpoint.

It’s a journey. You’ve been described as a conceptual designer. What role would you say conceptual fashion plays in the current industry dominated by overconsumption?

I wouldn’t actually agree fully agree with that title. I think of myself as more of an innovation designer, and my studio also takes a broader stance of design thinking into outcomes and processes.

Do you reject ‘conceptual’ and prefer ‘innovative’?

No, no, the ‘concept’ is still there. It’s regarding the title – it’s not about rejecting anything, it’s how we describe ourselves. I envision, imagine and strategise my role to be in here – I work on a broader facet of this topic. For me, thinking systems are really important. Sometimes, concepts really help to get a vision of how we can crystallise and execute. Everything evolves from a concept, and then production comes in to scale the entire mission. I just feel like it’s more than just being a conceptual fashion designer

Conceptual often implies not getting into the physical, which is not the case.

Not necessarily, I think it’s just a label. We could elaborate a bit more – it doesn’t have to be like that. I’m sure there are many artists, designers, studios, and start-ups that approach ‘conceptual’ from different angles. For me, with everything I do, there is an execution that comes after it. For example, if I conceptualise a new material or a way of making a garment or mobility or anything, I always think through the manufacturing process. I think it’s very important together with the vision of the concept. It’s for communication because if you don’t have that clear visual concept to explain to your team, public and stakeholders, then you have a problem.

Can you tell me about the piece you’re exhibiting?

It’s a step further from my previous work where I combine temporal materials with digital interference. It’s really about playing with time. This cultural piece is designed to have a performative quality. What is displayed is not the piece itself – it’s how it is changing. The process is what is on show. It’s the first time I’ve done anything like this, and it’s an honour that the museum let me. It’s risky.

I imagine it must’ve been quite nerve-wracking for you too, if it’s the first time.

It was an idea I’ve wanted to do for a long time – having something live under our control to a certain extent as it’s engineered. The piece is engineered by the biological processes of degrading and the structural engineering behind it. So really, it’s a combination between science and design but still allowing a bit of randomness. We respect the rule of nature.

How do you hope art instructions and exhibitions like this can act as agency change in fighting the climate crisis?

For the general public, we make them question how they see plastic, to look at it from an angle they maybe hadn’t considered before. For other industries, we have these discussions all the time as so many new products constantly come out. But for the public, I think it’s making a statement at this time in history. Collaborative exhibitions like this show so many different methodologies around how different disciplines can tackle the same issue. It’s a possibility to see all of these interpretations of how we can improve in one go. It’s also showing scientific research in a very creative way.

And an accessible way.

For sure.

What do you hope the future will look like? Either within your practice or in general, relating to the climate crisis and art?

We’re in very turbulent times right now, so I can’t predict the future too much. What I do, is almost a reflection of what I hope the future to be. I combine the physical and digital, and I don’t think it will go either way – I think it will be combined… with a positive impact. We’re already seeing explosive opportunities in the technological which includes biotechnology. To give a few concrete examples, recently I’ve been collaborating with brands like Rolls Royce, Vogue, and SHOWstudio, as well as museums. All of these different stakeholders are coming together to work with artists like me and showcase our research, and our reinterpretations of the future. I think the way of letting it out and displaying it inclusively is showing more and more, which is very exciting.

For sure! And this exhibition only adds to this new narrative.

Notifications