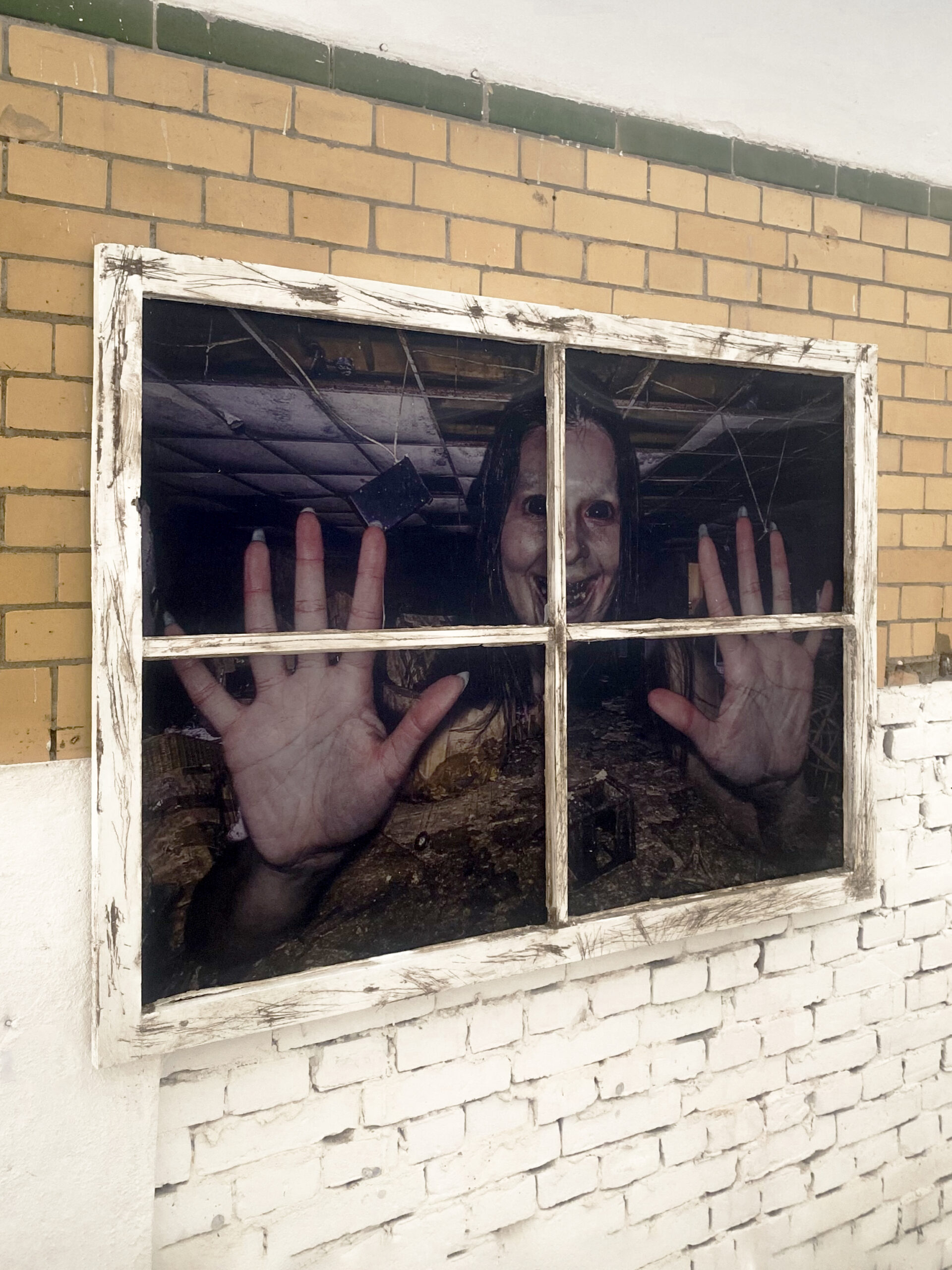

Lily Bloom — Washington, enticular print, wood, lacquer, 89 x 125

Unveiling a chilling exploration of the human fascination with violence and its interaction with modern technology, the group exhibition “Bloodsport” captivated audiences and artists alike in Amsterdam. Curated by the artistic duo Isabelle van Manen and Doron Beuns, known as Sodom & Gomorrah, this thought-provoking display was the second edition of their joint exhibitions, showcasing the works of thirteen emerging artists from around the globe. The exhibition, held under the auspices of Pim Lamme from Semester 9, a burgeoning contemporary art agency, delved into the delicate balance between our biological vulnerability and the perceived detachment from violence facilitated by technology. In an era where graphic images of brutality inundate our screens through news outlets and social media, one cannot help but wonder about the allure of these macabre depictions. Is it a morbid curiosity, a fascination with the limits of human endurance, or something more primal that draws us in? Through the compelling contributions of artists such as Bianca Hlywa, Dae Uk Kim, Harry Hugo Little,Ilse Kind,K.T. Kobel, Lily Bloom, Maggie Dunlap,Max Otis King, Melle Nieling, Thieu Kessels, Vera Kersting and Ton Damen, “Bloodsport” invited viewers to critically engage with these questions, offering a space for introspection and dialogue.

Tell me about the concept behind Bloodsport!

Doron: It was a group exhibition that delved into the encounter with gruesome images, particularly in an age where one lives within a relative peace bubble. We witnessed young artists from various cities responding to this prevalent cultural phenomenon, and we wanted to bring them together. The artists we encountered were mostly people who were already our friends or individuals we had previously worked with in previous editions. As a result, it came together very quickly.

Isabelle: Within Bloodsport, we talked about how the screen, as a buffer between us and the real world affects our perception of gruesome images. Furthermore how becoming desensitised to such images adds even more layers.

Totally, you’re always one hashtag away from something horrific on a platform like TikTok.

Doron: Exactly. For the exhibition, I knew many artists who within their independent practices responded to that reality. So, it all kind of happened quite naturally, we were following artists touching the same themes and exchanging messages with them

MELLE NIELING, Artemis, Looped video, flatscreen, hardware, cardboard, steel, 150 x 250

It’s so nice to hear that it came through this way. What do you believe that our underlying fascination is with gruesome images? Even though we are exposed to them all the time, I would argue that we are all drawn to gore in some way. Whether we’re exposed or not, It seems that people always lead their own way there…

Isabelle: I think that you just need your dopamine receptors to be active all the time. The algorithm gets more extreme by the minute. The same could be said about rich people and their hobbies, which are becoming more gruesome the more money they make.

You get bored of what you had before, you want something better every time.

Isabelle: Yeah. So, I think that’s where it comes from. It is also about watching something very personal and intimate. Also in porn, we see things we would never do in real life. You just keep watching it because you are curious. And then there is also an artistic side to watching gruesome images; people that look at these images for finding particular aesthetic qualities. But overall it is very much about keeping your dopamine receptors triggered.

Doron: But I think I think that’s only possible because the glass screen provides a buffer. If somebody were to be hit by a car on the street, you’d probably try to help. But you wouldn’t go closer to the body and look at the flesh of the open wound. It is the buffer that provides us with a safe boundary. Although, then there is Jordan Wolfson, an artist from New York,who did this piece titled ‘Real Violence’ where you would wear VR goggles and look at somebody murdering another person. You cannot say that it is real violence, but it kind of is despite the buffer.

Where is the line of violence? Is ideation of violence enough?

Doron: I think we’ll find out in the near future. You do hear things such as school shooters being inspired by video games. So, there’s always an analogue-digital bridge going on. But I guess, like in American culture, people take that to extremes.

Can desensitisation ever be a good thing? It seems to allow people to read the news every day, for example.

Isabelle: Good question. Maybe it helps you filter the world a bit more?

Doron: Last week, we received this question from Maria who is running Zgriptor in London. And she said, “What if you get an entire generation of people that is desensitised?” Usually, the way it works in evolutionary biology is that you lose a certain trait, and you obtain something new for it in return. So, the question is, what do we obtain in return?

Coinciding with global desensitisation, there has been an increase in people suffering from anxiety disorders. Some theorise it to be because we’re no longer (generally speaking) afraid that we can survive the night. Is there a correlation here?

Isabelle: Feelings nowadays emerge within us at such a fast pace. That’s why we’re all depressed. A friend of mine moved to a farm because she felt the need to be in the fields, run, and care for animals, children etc. This box we hold in our hands all the time is just driving us mad.

The internet makes things go fucking lightspeed. Yeah, there’s no time to process anything.

Isabelle: And that’s why people now have to meditate twice a week and go touch grass on the weekends…

Doron: We have to overcompensate by lifting a lot of weights or running marathons

Trying to become a warrior.

Doron: Well, more in a sense that you have to do things to get back into your body, to be aware of the fact that you have a body. Being on your device for like 14 hours a day makes you forget that your body exists. You have to find a remedy – running around the fields, foraging, hunting etc.

I think I’d like to go back to foraging.

Doron: But another thing we might be looking for is spiritual sensation. I think because most of us are spiritually void. We probably loved the sensations we used to get from religious experiences, so we now are looking for them in a secular realm. And it’s really hard to find something similar.

MAGGIE DUNLAP, Dead Body Found in Warehouse, laserjet print on alu-dibond, 140 x 100 x 0,5

DAE UK KIM, ELEKTRA, Tires, High heels, Silicone, PU, Metal tube, 75 x 43 x 65

MAX OTIS KING, I fed myself chocolate, then a string cheese and then a red pepper, 3D printed filament, wood, steel, lacquer, graphite, 85 x 85 x 75

THIEU KESSELS, HUMAN MASK SERIES, Glass, uv print, 50cm x 50

DORON BEUNS, SURGICAL MOSAIC SERIES, Plastic rhinestones on canvas and perspex, 40 x 32

I also think, briefly talking about myth and conspiracy, people are searching for that same feeling online. And that usually ends up within the conspiracy narrative.

Doron: They’re just looking for meaning. Because sometimes even if you’re presented with facts, they don’t make sense to you within your symbolic superstructure.

Isabelle: Yeah. It’s scary.

So, going back to the exhibition, was there one motif that you saw running through each of the artists’ works? Like one particular narrative, or maybe tell me about different narratives that each of them explored, that you thought were particularly interesting.

Doron: It was very scattered – a lot of different approaches to the same subject.

Isabelle: That’s also what we wanted – to do an exhibition that showed different angles on suffering and pleasure in this technologically advanced society. I think that all of the artists in the show had that thematic arch in common, although the way they translated that into their work was very different. For example, There was a sculpture by Dae Uk Kim made from tires that looked like a human body with both very masculine and very feminine features. A totally different example would be Maggie Dunlap. She has been exhibiting fictional images of crime scenes that she would then distribute online. This is on one hand a social experiment, but also an investigation into the aesthetics of crime scenes.

Doron: She makes these very convincing fictional crime scenes with female corpses, but they are actually just models with special effects makeup. But she certainly convinced some people on Reddit.

Also, the fetishization of female pain is huge

Doron: Yes, I think Maggie Dunlap calls it the Death Girl Industrial Complex. She apparently listened to a lot of crime mystery podcasts, and then she became aware that something like 70% of all serial killer victims were women. And then 70% of all people that listen to these podcasts were also women. Not sure if these numbers are exactly right, but there is certainly an entire industry of women consuming the pain of other women.

Isabelle: I feel like women love to exhibit their own pain. And I think that femme men also like to do that.

I think particularly when it comes to the crime podcast, it’s almost like a community itself with people mourning the women’s pain, but then also taking pleasure (or entertainment) from it.

Isabelle: Also, because there’s not enough happening in their own lives. People are always looking for danger. Maybe that’s it?

Doron: It grinds your gears. You have to challenge yourself to overcome your limitations. Overcoming limitations has been on the human agenda for the past couple thousand of years. It is hard to stop doing that all of a sudden. We have always bargained with the present to then move into the future.

And in curating the exhibition, was there a goal that you wanted the audience to take away and a feeling that you felt you wanted the audience to be impacted by and then walk away from?

Doron: I think that the responses were varied in the sense that probably a lot of people were confused and disturbed by what they were seeing. And then there were people, probably the ones that stayed longer, that appreciated the aesthetic nuances in the work. So, all of a sudden one could see all of the beautiful colours contained within the human body. Or how Max Otis King, who upscaled a brain chip into a medieval torture device achieved a beautifully sculptural form.

Isabelle: I think the exhibition also shows how everything comes together in this crazy world of ours- humans, machines, animals. Also isn’t it crazy how we can literally sell body parts these days? You can really have it all.

Doron: Yeah, like dirty panties.

Isabelle: Everything you put online gets a life of its own.

Doron: Yeah. And then it starts interacting with non-human elements like algorithms, which then decide how the content develops online.

Isabelle: I think that the place that we are in has its origin in the commodification of new technology.

This is interesting because the technology itself is commodified, the gruesome image itself is commodified, and the pain is commodified. And then you buy interactions with it. Watching a podcast or a movie or viewing art – we’re also commodified.

Doron: I think we sold one little drawing, but technically everything was for sale. It was a different audience.

Isabelle: We really wanted to stage an experience with this exhibition, and we really felt the need for it here in Amsterdam. And yeah, it was actually really satisfying.

Doron: The dear sales agent that we worked with was probably a bit less pleased with the theme and selection of works because it is exceptionally difficult to sell this work to a private collector. It is very charged work. This is typically not the kind of art people would place in their home.

People probably don’t want to admit that they are drawn to gruesome images. And by buying something, then you’re completely admitting that you’re finding pleasure in such images.

Doron: But then I wondered what’s the difference between that and a horror movie? Well, I guess I can turn a horror movie on and I can also turn it off again. But if I had an artwork up in my house, I can go to the other room, but it will still be there.

And also, what will other people think of you? Would people think you’re a psychopath?

Doron: There are obviously characters that love to play with the cliches and expectations that come with this work. I personally wouldn’t mind any of that stuff in my house.

I also think maybe it’s very different for a man to have an image of a dead female body in the house than for a woman.

Doron: Probably. I could easily imagine it in Patrick Bateman’s apartment from American Psycho.

Isabelle: Yes. And it’s a female director, by the way, haha!

HARRY HUGO LITTLE, Filth, Oil on board, 18,5 x 24

Do you have a hypothesis for the future when it comes to things like gore and technology? Do you have a feeling as to where we’re heading with it?

Isabelle: I think that technology makes me less scared to grow older. I can just operate everything with a brain chip. I can still talk to everybody through my devices. And when it comes to art and gore, I think it is going to become more extreme. It’s either that or everything goes back to basics.

Doron: I believe that this shift towards gore is a direct response to the sterility and apathy prevalent in modernism and abstract painting. When you think about it, these artists who work with gruesome images are essentially reconnecting with reality—the reality that exists beyond our peaceful bubble. Perhaps we will become completely desensitized to this type of art. However, through that process, we may also become less fearful of physical decay and death. It is possible that we can develop a healthier perspective on physical fragility and mortality. Yeah, I mean, that’s a bit of a hopeful take on it.

Isabelle: I also think because we are coming out of this age of extreme minimalism – everything is white and clean and bare. Every millennial home looks like a dental clinic.

Doron: And our artists came through with the patients

Isabelle: We are basically responding to a collective trauma, the Corona pandemic. Everybody is so keen on making either a dystopic or a utopic version of the world through tech. People live for it.

Doron: Yeah, on one side, there is this new world-building narrative with a very moralistic stance. And then there is this other black-pilled dystopic and arguably more realistic take on our contemporary circumstances.

And do you have any plans for a third edition?

Isabelle: Not really, at least not anything concrete yet. I think we’re still waiting for the spark. I think we’re staying in this corner of investigating tech and culture, but maybe there are some other things we can tap into. Who knows?

Doron: I mean, we could potentially make a move to the opposite end. Maybe with the next exhibition, we could explore and attain utopia.

Isabelle: I like the idea of Coachella on steroids.

At Glamcult, we have Utopia, Dystopia, Pain and Pleasure. You could always do the same! Also focusing on pleasure. It could be on pornography but not necessarily. I just wrote an article on hentai and the censorship of the genre. Even though it’s a cartoon, they censor out the dick but not the vagina.

Isabelle: I’ve heard a lot of men say that they don’t want to see a dick, that they only watch lesbian porn. Maybe the anime makers are also grossed out about it.

I think censoring makes it more real.

Isabelle: This also seems to apply to the whole Balenciaga scandal, with the kids and the kinky toys. They censored the kids’ faces, which for me, made it actually uncomfortable. Otherwise, I’d just think it’s a kid with a weird toy.

It questions what’s happening underneath the pixels.

Doron: This definitely drew a particular kind of attention to it.

Isabelle: The mystery makes it more exciting or scary, I guess.

Doron: I had similar thoughts about the recent coronation in the UK. To me, it felt a bit stale and boring because it was so HD. I’d prefer a more vintage and grainy version, it would’ve given it more mystique.

Isabelle: Monarchy has historically been about mystique, but now it’s just so accessible.

I mean, fuck the monarchy, but yes, for so many years they battled with this idea of keeping secrets, and not breaking this barrier (which a live broadcast naturally does).

Isabelle: Yeah, I think they’re breaking it now. I don’t think they should, like, stop flaunting money in people’s faces!

When people can’t afford to turn on the lights at home…

Isabelle: That’s also the thing, people are fed up with the Kardashians flaunting their money and first-world problems. It was nice in the beginning, but it’s really getting out of hand.

Doron: Like with old movie stars, you’d only see them in films and red carpets. Now we see them walking down the street with a coffee.

Maybe it’s the same as with the dick in hentai – if you see too much of it, it ruins the magic.

Isabelle: Yeah, image fatigue.

Doron: To circle back to what we were talking about what’s next, we’re trying to continue the conversation by opening up many other conversations

Your work is also based on research heavily, so you can’t just go on to the next, it takes time.

Isabelle: Maybe we are also taking a lot more time this time around. Really going in-depth and learning from the past.

Doron: On a practical level, we’re really out of money. All we can do now is talk, ha-ha. We’re looking for sponsors now, and I can envision the next exhibition being outside of Amsterdam, at least partially. We will however always try to maintain the part of facilitating a dialogue between emerging artists from different cities. This last exhibition for example was very much a conversation between Amsterdam and London.

I can see why regarding the subject, and our crime rate in England in comparison to Amsterdam.

Isabelle: But also here in Amsterdam, there are shootings every day.

Doron: Yeah, but mostly on the periphery of the city, in the more economically struggling areas?

I guess that’s the difference, there isn’t as much geographical separation in England. Estates and the unimaginably rich can live on one another’s doorstep.

Isabelle: I think Amsterdam is quite comfortable, there aren’t that many visible crimes or wealth gaps. People are not really pushed to work extraordinarily hard or make art.

Doron: There is less of a deep need for art to console you. When I went to New York for the first time, I really noticed that music played such a different role in society than it did here. People had this existential need for music.

Totally, I mean genres like drum and bass, jungle, and punk all come from this existential need for relief, and I think there hasn’t been a new, revolutionising sound, here for a while.

Doron: It makes you a bit less vulnerable. For example, in the UK it is extremely expensive to study after high school, it is really not for everyone. Here, it’s 4 years of fun, and back in the day, you could even get a part of the money back when you graduated.

Isabelle: If I graduate this year, I get a small discount, but I’m still 20k in depth.

And 20 is really not a lot these days ha-ha!

Isabelle: Yeah, but with these rising living costs we still need to think of a way to get rich.

Let me know if you come up with an idea!

Words by Grace Powell

Images courtesy of the artists via Bloodsport

Notifications