As proud official media partners of The Holland Festival, we speak to the renowned American choreographer about his artistic journey and up-and-coming projects.

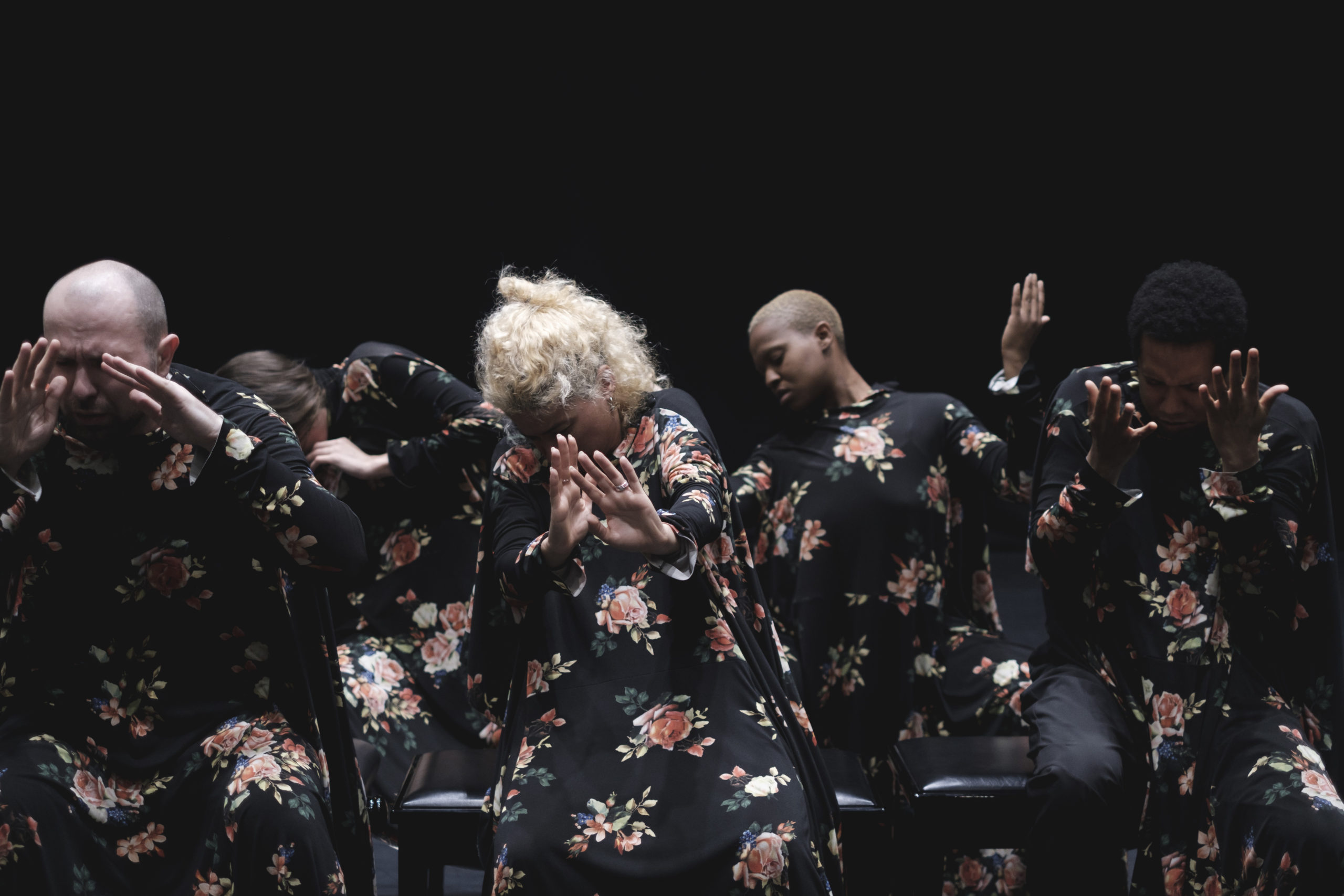

If there’s one thing that American choreographer Trajal Harrell makes us feel with immediacy, it has to be a sense of togetherness. The Douglas-born, Athens-based artist, is one of his generation’s most renowned choreographers, with an extensive, decades-spanning, career and an unparalleled devotion to finding revelatory abundance in seemingly opposing forces.

This summer, Harrell will premiere a new trilogy, Porca Miseria, at Amsterdam’s Holland Festival. The work is based on three different, but equally compelling, women: Maggie, from Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof; the African-American choreographer and activist Katherine Dunham; and the Greek mythological figure, Medea. True to Harrell’s vision, Porca Miseria promises to develop his practice of redefining established barriers between the disciplines of dance, theatre and performance art. Or, in his own words: “I always try and apply to my work something that Toni Morrison once said: If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

How has your dance language evolved throughout the years?

I think that when I first started out, I was very naïve, I really thought that I would develop my own style and dance language. I went for it all the way, and I mean, it kind of happened, which is sort of strange. At first, I was working on post-modern minimalism and its ideas, but trying to work through them in my own way. Then I got introduced to voguing! It showed me a world where fashion language could be utilised as a dance, and that was very big for me. The first piece I did at the Judson Church explored what would happen if voguing was minimalist. Of course, voguing is not a minimalist procedure, so for me, that spurred a new way of thinking and developing performance, the language of dance and the history of dance. I think the thing I developed and contributed most extensively to the history of dance was evolving runway-language into its own dance-language and formalism, which has been the basis of my work for 21 years. However, since 2013 I’ve been on another long-term search, and that’s looking at Japanese butoh dance. I look at this avant-garde dance practice through the theoretical lens of voguing, but I’m also looking at modern dance through the theoretical lens of butoh. The runway, though, is always there.

You incorporate a lot of dance history into the process of making your work. How do you translate that to the general public?

I try to guide the public in the work. If I feel that it’s really important, we give the history. I have the guide, who can be someone that speaks or hands out information; it’s quite similar to the way museums function. However, if I think this information is unnecessary and gets in the way, I also take that into consideration.

You will present three works as a trilogy, Porca Miseria, this summer. Two works premiered last year—O Medea at Onassis Stegi in Athens and Maggie the Cat at Manchester International Festival—and The Deathbed of Katherine Dunham will be presented in April at Schauspielhaus in Zürich. Yet, the three see their premiere as one at Amsterdam’s Holland Festival. Is there a reason you’ve chosen these particular works?

I was interested in rethinking the notion of the bitch. Of course, in ballroom culture, the term “bitch” is an honorific title, but we know this term is also often used to degrade or disempower women. I wanted to look at that, so I chose three female characters that might have been associated with that word, and rethink it. The first was Maggie from Tennessee Williams’ Cat on the Hot Tin Roof. The second one is the deceased choreographer and African-American activist, Katherine Dunham. The third person is Medea, from ancient Greek mythology, who was, and still is, known as the ultimate bitch for killing her children. I’ve made the trilogy in a way that it’s not a durational work; you don’t have to watch all three. You can choose to watch work 1, 2 or 3; together, or on different nights, and in whatever order you wish. Like my earlier work with series, it’s very option-based.

Was the process of making these works similar in approach for all three of them?

It’s been a very different process for each one of them. The first one I made was Maggie The Cat. During my two-year residency at MoMA, I started looking at the differences between the performance in theatre and the museum, and then at the relationship of installation practice and sculpture practice in the museum. I started with a lot of those ideas while making the work, especially Maggie The Cat, as I tried to bring them into the theatre space

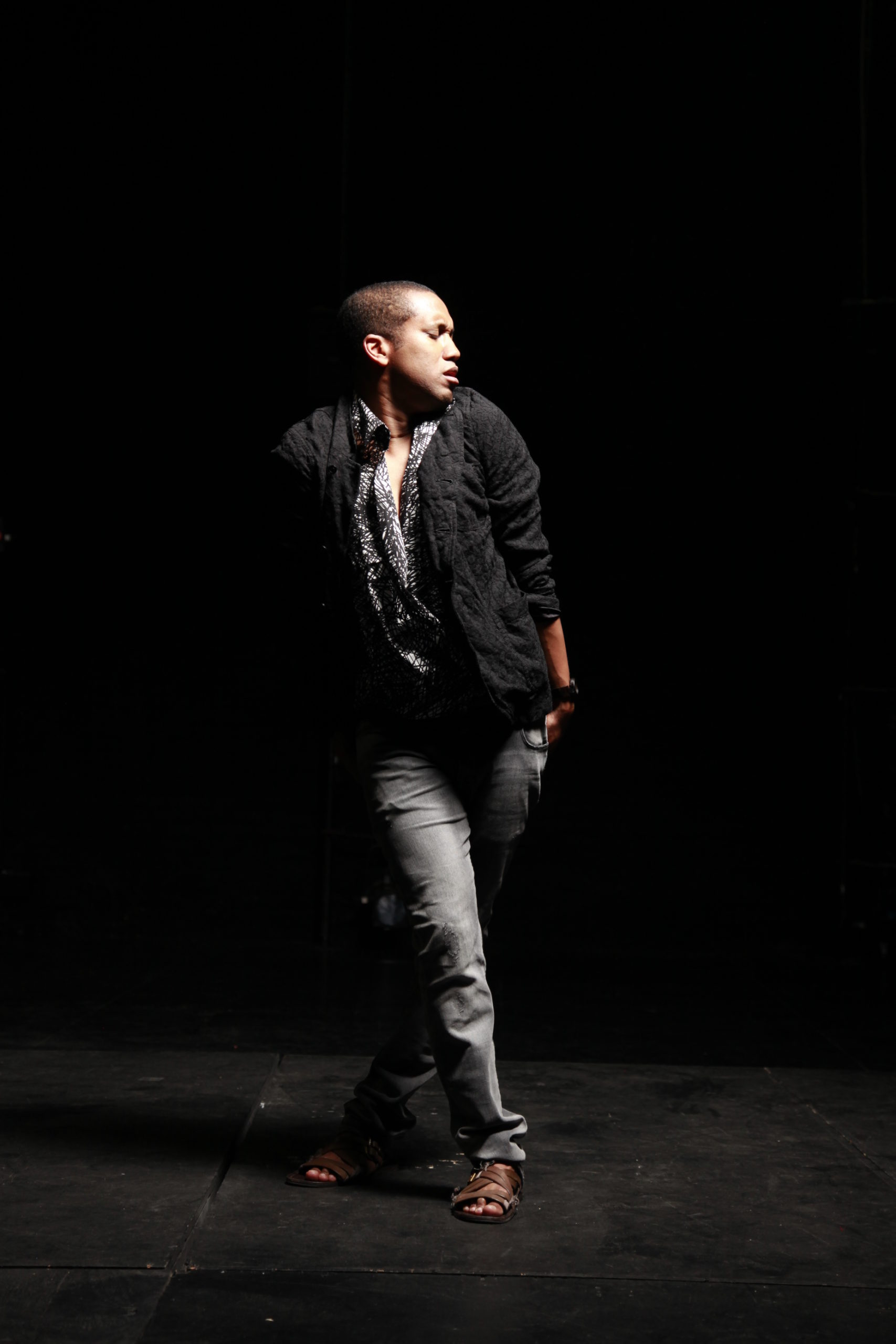

Photographer: Waleed Shah

Do you consciously think of the spaces where your work is shown? What’s the conversation that the spatial realities of theatre and the museum have within your work?

With this piece [Porca Miseria] in particular, I was thinking about how work transfers, and during the MoMA residency I was trying to make a circle of influence between the museum and theatre work. I wanted to refresh the work, but also create new possibilities. Museums were opening up to dance in large, as previously it was mostly seen [as belonging] exclusively to the theatre. This transferring is the exact thing I’m working on in a lot of the work. There’s this piece I made in 2017, Juliet and Romeo, in which I tried to make an installation in the theatre that operated in theatre time. So, by focusing on those kinds of thoughts and tensions, it’s a completely conscious process.

Alongside this consciousness, how important is intuition in your work?

I work like an “action painter”, perhaps. When I work, I try to trust myself in the process and be very present in the moment with the work, the materials, and performers. I always try and apply to my work something that Tony Morrison once said: “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” I often think about that in terms of dance. I make the kind of dances I want to see. I trust that there are people out there, similar to myself, who also want to see these dances.

Very much so! Being a dancer myself, I must say it’s a pleasure to see a person of colour in these spaces, making avant-garde and conceptual works, and being recognised and awarded for them.

Thank you! I’m glad you mention that because it’s something that I think about as I get older. I think that on a certain level I’m just doing my work, but I do realise that it’s special and there aren’t many people that look like me and have had the visibility that I’ve had. I’m honoured, and I only hope that it opens up more doors for people.

Do you think there’s a difference in the way audiences perceive your work in, let’s say, Europe as compared to other parts of the world?

In the beginning, yes. Now people know my work, so that difference is maybe not as evident. Of course, in every culture, there’s going to be a lot of differences. For example, a big difference was that most people in the US were familiar with voguing. So they got some of the references much more easily as compared to people in Europe, where they saw something they didn’t know and yet were perhaps very excited about. But now, I think it’s not so much of a difference, other than the differences you would normally have between different localities and cultures.

Speaking of voguing, I’m part of the ballroom scene here in Europe, which is still pretty new. I’m curious to know what your experience has been with ballroom culture?

I went to my first ball in 1998, so that’s 22 years of research and following ballroom culture. I have the deepest respect for ballroom culture. It goes without saying, I am not a voguer and I do not vogue. It’s very important to maintain this distance. Also, I think the biggest thing that ballroom gave to me was a particular way of dealing with performance. The audience at balls is completely different than the one in the theatre. You don’t have this perspective of the centre, I think ballroom performance just has its own logic, which is primarily based on social performance and how people communicate in the room at that very moment. This urgency and immediateness is something that I’ve really brought to my work; a result of going to so many balls and seeing that energy.

Indeed, there’s definitely a sense of immediacy—from the person walking a ball to the audience in that space… For this issue, Glamcult just so happens to be exploring urgency. How would you relate that to your own work?

I had an acting teacher, who used to say to us, “If you don’t have anything to say in the theatre today, don’t come.” That made a big impression on me because what I’m speaking about and trying to express in my work today has to have immediacy. I have to have a need, and I also want this need I have to be shared together, between us, in a moment that only exists here and now. I hope I make people feel that they want to be present for it in that very moment.

There also seems to be a sense of reimagining realities, would you agree? What would a reimagined future look like from Trajal’s perspective?

You know, I try not to go too far into the future. I’m very excited about the now; the present looks a lot better than I thought it would. I think the work that we’ve all done with gender and sexuality—although we are still facing problems—has opened the possibilities of who we can be in terms of our identities. We have a group of people who will not necessarily know of the huge struggle and the fight; they’ll grow up thinking that all these possibilities just exist. On the one hand, that’s something that I think is completely wonderful. As a young boy growing up in Douglas, Georgia, I assumed we would have a little bit of change, but the changes we’re starting to see are remarkable and I didn’t think I would see this in my lifetime. Of course, we have opposition to those changes as well, that’s for sure.

Is there a particular feeling you want your audience to walk away with after experiencing your work?

A person is going to come with their very own set of expectations and depending on who they are in that very moment, that will affect their perception. But the one thing I say I always work on is that I want us to feel [a sense of] togetherness. We are together in a room, and this is something we can only experience at this moment. The togetherness we share is part of the subject. This is very important to me.

This interview was conducted and printed before the corona crisis started. For any updates, check Holland Festival online.

Porca Miseria 26-27 June

International Theatre Amsterdam

Photography by: Nick Knight, Waleed Shah, Orpheas Emirzas, Tristram Kenton

Words by Arnold Arakaza

Notifications