In conversation with the artist, performer, DJ, writer and nightlife icon.

Triptych, 2018, photography by Maurice Haak, courtesy of Rewire Festival

On 19 March, NYC-based artist Juliana Huxtable shared Andrea Long Chu’s essay “On Liking Women” on Twitter. Written in her unmistakable style, the tweet read “@theorygurl JUST BROKE ME OPEN … ONE OF THE BEST ESSAYS IVE READ PROBABLY EVER … A MUST FOR ANYONE, BUT ESPECIALLY THOSE INTERESTED IN CONVERSATIONS REGARDING FEMINISM, TRANSNESS, DESIRE & IDENTITY (WHATEVER THAT MEANS BUT U MUST MUST READ)”. Two weeks later Huxtable presented her performance Triptych at Rewire Festival in The Hague, and spoke with me about her work. In preparation, I read Chu’s essay, and it haunted me. All the many projects Huxtable works on and the themes she addresses somehow come together in this one text that, surprisingly, is neither about her work nor written by her.

When I say “many projects”, I really do mean many projects. In 2017, Huxtable published not one but two books: a volume of her ALL CAPS poetry titled Mucus in My Pineal Gland and another story, co-written with her partner Hannah Black, called Life: A Novel. Her performances have been staged around the world and in the most prestigious art centres of her adopted hometown, including the Museum of Modern Art and the New Museum. But most of us probably know her from the space where great art often finds its origins: New York City’s Queer Nightlife. As a DJ, she’s played everywhere from Boiler Room to Berghain, and probably all of your favourite Brooklyn spots from Bossa Nova to Trans Pecos. On top of that she hosts her own party, Shock Value, where she invites artists such as Le1f, Princess Nokia, Bunny Michael and Lafawndah. As anyone in this network will tell you, Juliana Huxtable pushes an intellectual, artistic and musical culture that has a huge influence on the worldwide queer community.

@theorygurl JUST BROKE ME OPEN … ONE OF THE BEST ESSAYS IVE READ PROBABLY EVER … A MUST FOR ANYONE, BUT ESPECIALLY THOSE INTERESTED IN CONVERSATIONS REGARDING FEMINISM, TRANSNESS, DESIRE & IDENTITY (WHATEVER THAT MEANS BUT U MUST MUST READ) https://t.co/8l2vnvvxkJ

— MATURE PROFESSIONAL (@HUXTABLEJULIANA) March 19, 2018

And so, it’s not surprising to find her work well represented in an essay such as “On Liking Women”, which inverts and subverts the most current questions surrounding queerness. Chu’s text creates a fundamental debate about the connections between the personal and the political. About the connections between our deepest desires and our identities—as women who want to be women and as women who want to love women. She analyses the hottest aspects of those debates: political lesbianism, trans exclusionary radical feminism and identity politics at large, creating a mirror in which we see ourselves reflected full form. What the mirror shows most clearly is that the ways we try to understand all these aspects of our identity, how they function in the world and what they mean to us, might be more about what we want to be than about what we already are. Indeed, Chu’s approach recentralizes desire in the quest to understand identity. It makes sense that we find many parallels between the work of a politically committed, black, trans female artist like Huxtable and this essay. Even when the themes of Huxtable’s work are more explicitly described as conspiracy, paranoia and distrust, a discussion about desire always runs beneath them. For what is conspiracy, if not the desire to bring to light hidden truths? And what is distrust, if not an expression of that desire?

Triptych, 2018, photography by Pieter Kers, courtesy of Rewire Festival

Feeling absurdity

So far, Huxtable’s exhibition A Split During Laughter at the Rally, which was on show at Reena Spauling’s Fine Art in New York during the summer of 2017, explored these questions in the most explicit way. With imagery connecting online aesthetics to whatever we may understand as protest aesthetics printed on poster-sized prints and buttons, Huxtable questioned both the message and the appearance of a widespread distrust of mainstream messages. While our feeds clutter with fake news, think pieces about fake news, a reaction to the think pieces, a correction of the think pieces and an addition to the think pieces, Huxtable’s work is not so much a comment on this process (which surely we already have in abundance) as it’s an engagement with how it makes us feel. Departing from this feeling she asks what we learn when we stand still at what are, in her words, productive moments of disillusionment and absurdity.

A Split During Laughter at the Rally includes, for instance, a video of a fake rally that Huxtable set up after she attended a real one with her friend Bailey and was left feeling disillusioned with the process of it. “I felt disillusioned not just with the structures of power but also with the formats for political engagement that currently exist. I felt a little bit of absurdity. Bailey and I went to a rally together right when Trump got elected. In this time, every week a new hyper dramatic policy happened. Like, ‘This week all black babies will be grinded with a meat grinder,’ and that’s a policy so now we have to go protest that. This happened back to back to back, to the point where I felt like I was intentionally exhausted. When a protest was set up because they were banning gender non-conforming and trans people from going to the bathroom, Bailey and I figured we should probably go to the protest. But while we were doing this and holding signs and singing chants, both of us looked at each other and we burst out laughing. It felt like a really productive moment and that jadedness and tragedy, but also comic moment, was a place I wanted to work from.” The resulting exhibition conveys this feeling through a mixed-medium message. Combining the aforementioned posters and buttons with video, an assemblage of what we know as “protest” is created that both shows its urgency in the current political climate and the way this climate is making engagement with any political message impossible, exhausting or, often, absurd.

A Split During Laughter at the Rally, 2017, digital video, running time: 21:41 minutes, courtesy of Reena Spaulings Fine Art

Protest aesthetics

It seems telling for a political moment that is really showing the failure of democracy in the American context to find a nation that desires to engage more deeply with modes of protest—whether that’s going out to a rally or posting a political message on a social media feed. What the methods and approaches to this should be, however, is increasingly hard to tell. Protests and posts feel hollow when the majority of votes still couldn’t put a woman who was ten times her male opponent’s superior into office. But there are other levels on which disillusionment with the methods of political engagement is playing out. What about an H&M tee with a feminist slogan? What about the (white) Women’s March posing for the ’gram? What about a $500 Prada top with a picture of Angela Davis on it?

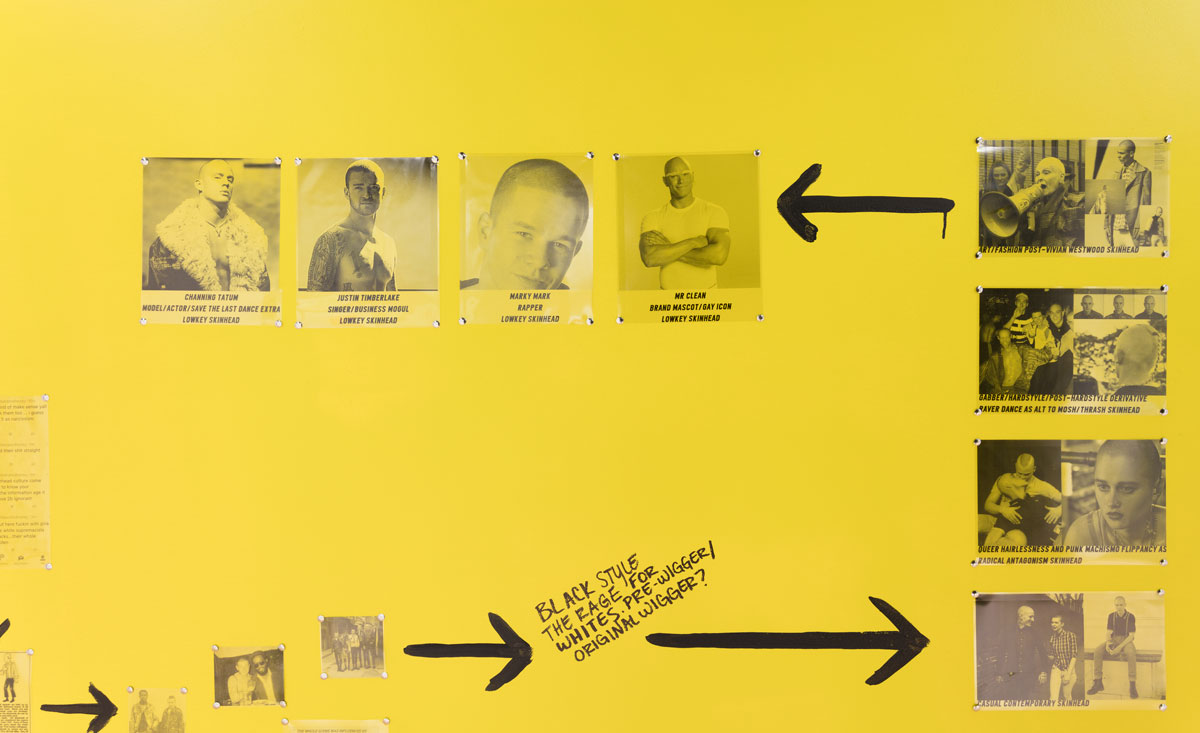

On these mixed messages, Huxtable says: “I think one of the alarming and difficult things about the contemporary moment is the inability to identify what a leftist aesthetic looks like. What a radical aesthetic looks like. Because at a certain moment you could look at people, and look at something they are wearing, and think, ‘Okay, they’re probably not voting for Trump.’ There are certain markers that you accumulate through navigating life and there’s an idea that there is, in fact, an aesthetic that represents what it means to be radical or leftist or Marxist. Any sort of signifiers that, at least at one point, I was searching for in the world. And then I realized that was impossible in a lot of ways. Especially in the meme-era context, aesthetics are really easily co-opted and that’s happening constantly. And so, the idea that you could identify or promote an aesthetic and assume that it carries some sort of radical message is maybe impossible. So I started thinking, What was the last time that you could look at something and identify it has a clear sort of ethical, social or political intent behind it?”

Huxtable’s questioning of the “memefacation” of a radical message can be found in her art practices beyond the galleries and festivals. Her Twitter account is a good example of the way she practices multidisciplinary art. At the time of writing she had just changed her profile name from (UN)AMERICAN BITCH to FREE THINKER—two examples of viral internet moments (one in the context of the White House’s “Muslim ban” and the other in the context of Kanye West’s public support of Trump) that deal with the questions she’s asking about the huge gap between what is said and what is intended. They’re labels used as much on the right as they are on the left, devoid of meaning while looking for the most self-righteous explanations of good politics. And—not unimportantly—they generate clicks.

Trolling the idea of trolling

In “On Liking Women” Chu extends her argument about the ways in which Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERFs) are often read as an anachronism to a commentary on the way the internet facilitates such thinking. She says the conflicts caused by TERFs have “as much to do with the ins and outs of social media—especially Tumblr, Twitter, and Reddit—as it does with any great ideological conflict. When a subculture espouses extremist politics, especially online, it is tempting but often incorrect to take those politics for that subculture’s beating heart. It’s worth considering whether TERFs, like certain strains of the alt-right, might be defined less by their political ideology (however noxious) and more by a complex, frankly fascinating relationship to trolling, on which it will be for future anthropologists, having solved the problem of digital ethnography, to elaborate.” Perhaps Huxtable is among those anthropologists, visiting us from the future to deliver an artistic engagement with the ways trolling effectively took over an entire presidential campaign.

She explains: “Generally I see my art practice as trolling. Or trolling the idea of trolling. Or utilizing the idea of trolling. Because one of the things that I find has radical potential is conspiracy. What I find really fascinating about conspiracies is that there are all these strange places where you find bridges. In the conspiracist’s mindset, the rabbit hole distrust and paranoia leads you down, but there’s more chance you will find common ground with someone than I think you will in a contemporary model of ‘I relate to other Republicans because I generally have this idea of the state relating to finances,’ or whatever. And I think a lot of people that are often written off as conspiracists are often just coming from a place of disenfranchisement.”

Such a sense of disenfranchisement is not unfamiliar to Huxtable herself., as she explains in the context of one of her earliest shows, Universal Crop Tops For All the Self Canonized Saints of Becoming(2015): “At the time I was working through the feeling of abandonment and being disenfranchised of the idea that there is an archive that I can access of the web. I wanted to go back to the websites that I would go to when I was 11 that totally radicalized my view on the world. The websites that fundamentally changed the way that I relate to my identity as part of the diaspora. I generally feel nostalgic for this time and it can be sort of toxic and stunting on evolution to be in that place. I asked myself how I can move on beyond this. I started to think about the ways in which people are dealing with a crisis of identity, because a lot of what I was dealing with as a set of desires actually related to my identity. The web was my place to go because I’m not taught anything in school that’s even vaguely affirming me as a human being.Turning to these websites was really radical, I think there’s a sort of new media in this really specific way, allowing for a more playful way of dealing with questions of history and participation or your own relationship to it.”

While the playful sides of new media are easily dismissed by an understanding of trolling that shows the ways it ridicules and oppresses people, Huxtable flips the way we generally interpret the word “troll”. What if the person on the receiving end of the trolling turns these methods around—creates a mirror? What does this mirror show? How does this reflect the desires of, for instance, an alt-right troll?

Untitled (Wall), 2017, paint and images printed on vellum, dimensions vary, courtesy of Reena Spaulings Fine Art

The war on proof

Questioning what we have access to on the web continues to be a theme in Huxtable’s work. In her 2015 performance There Are Certain Facts That Cannot Be Disputed at the Museum of Modern Art, for instance, we encounter an engagement with questions of truth in the online world that speaks to contemporary anxieties. Huxtable’s approach is, again, multidisciplinary. Spoken-word poetry meets cyber visuals, electronic sounds (by, among others, Elysia Crampton) combined with Sadaf H. Nava’s live violin and vocals. In the middle we find Huxtable herself, dressed in angelic white. Being and existing online generally brings about a set of questions about a fracture between an online and offline world, about the ways in which the online world is stored and how it’s employed to create a certain narrative, both personally and politically. Who do you desire to be online? And how can you use digital spaces to create that reality while the digital can also be used against you, to frame you as, let’s say, a terrorist if your google searches are considered suspicious?

“When it comes to discussions about larger ideas of data or the net, or how these things function, I try to challenge or undermine the idea that the internet is this monolithic space that has a dictated set of rules. Because as much as there are very valid and alarming concerns over the intrusions of privacy and the monitoring and mining of data and things like that, I also am wary of the idea that everything online actually exists. It’s almost like the question of whether or not everything that’s been documented exists is sort of secondary to how we access that. How databases are organized. How information is circulated. Because there are also a lot of things about the net that disappear.

“So, the idea that you can always know what you are seeing has really become a battle over proof. The clearest example, or the most absurd example, is when Trump was elected and he would say, ‘I had the most people that we ever had at the histories of inaugurations.’ And then someone would respond and say, ‘Well, actually we had more people at the inauguration of Obama,’ Or, ‘Actually, there were more people at the Women’s March.’ And then someone would say, ‘Well, actually this could all be Photoshopped.’ And then it just becomes this rabbit hole of people throwing images at each other—but they’re all convinced that somehow they’re going to convey an idea that you can prove what the actual inauguration population was. That was a highly symbolic moment of the failure to identify an idea of truth.”

A Split During Laughter at the Rally, 2017, digital video, running time: 21:41 minutes, courtesy of Reena Spaulings Fine Art

The desire to be

The panic over truth is showing how much of any political debate in this moment is playing out at the level of desire; the desire to see your own truth reflected, or even just the desire to see any truth reflected. By using themes such as proof, the web, paranoia, conspiracy and distrust, Huxtable is offering a profound reflection on what it means to claim, reject and shape an identity in the contemporary world. Her practice is a true engagement with the complexities of our zeitgeist, and illuminating on a level that’s not just artistically interesting, but also truly rooted in a social commitment, by showing us not only what we want for ourselves, but also from each other. Because, “What is it about Alex Jones or any right-wing conspiracist who says, ‘I want my gun,’ but not, ‘I want my gun because I’m down for the NRA,’ but, ‘I want my gun because I distrust the federal government and I think they might one day try to take my land from me’? How does that person, who also distrusts mass media and is buying organic, relate to the gay couple at the health food store who are also buying organic and also distrust the government?

“You know, there are these weird linkages and so I think framing things in terms of desire, and especially desire that is related to a set of questions, has a lot more radical potential than a sort of identity politics model, which inherently places people in these antagonistic relationships. Or relationships that have to be about opposition in order to then find resolution or something like that. I like this idea that thinking about and seeing someone’s identity and questioning where their desires are coming from—instead of questioning what is actually being espoused. Especially with TERFs, but this also goes for things like working-class white racism. This is not really about you actually hating black people or immigrants. It’s about a sense of political disenfranchisement, we actually have more in common than the people you are idolizing. And so the question is: how can you access that sense of solidarity? I feel like trolling—as a sort of playful relationship with the idea that identity ever could be presented—maybe opens up a space to work through this…”

Words by Emma van Meyeren

Follow Juliana Huxtable on

Soundcloud, Instagram and Twitter