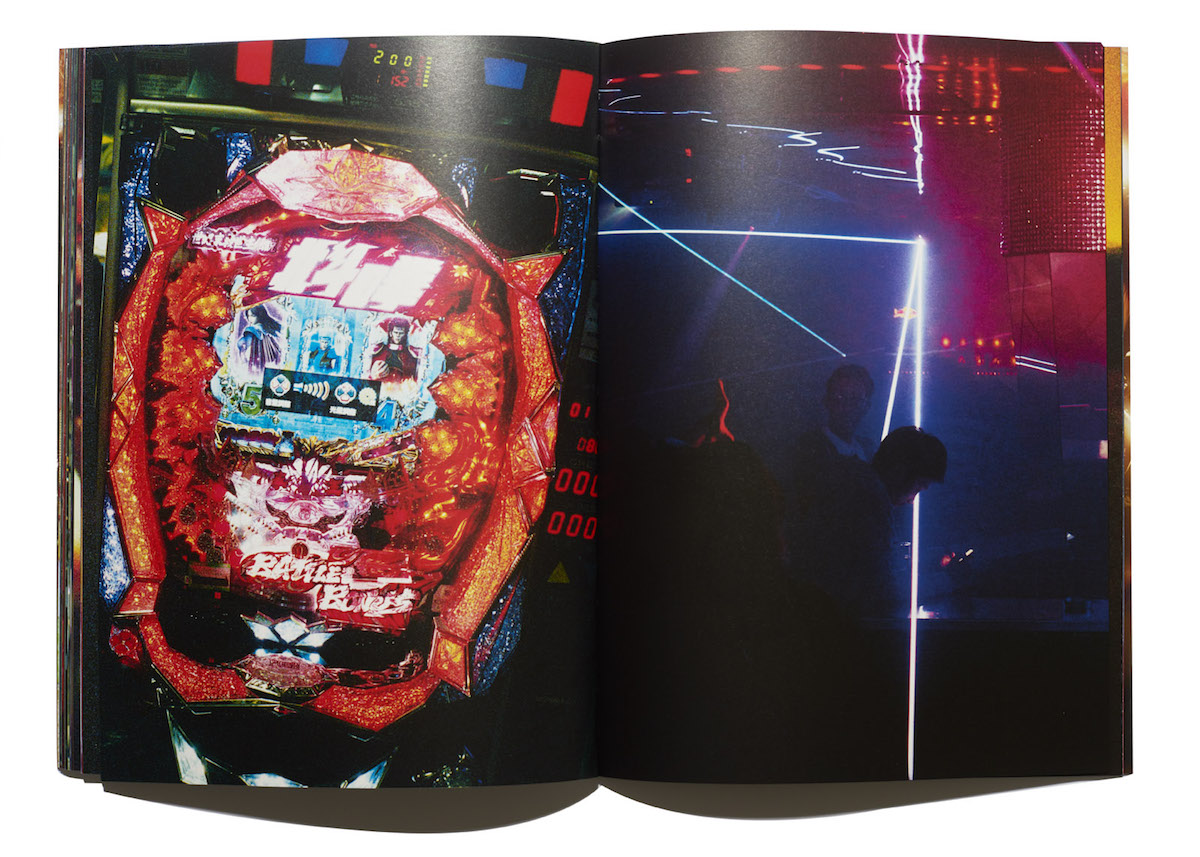

Immerse yourself in the pulsating chaos of the photographer’s images.

In Bloom

Wanderings through Tokyo nights, a rave in a forest, and countless mistakes eventually add up to emerge as Jean-Vincent Simonet’s captivating photographs, if you can still really call them that. Simonet is someone who lets his images speak for themselves, and you may have all kinds of preconceptions about his photographic reworks of reality. One thing is apparent: the (almost) living entities that arise after a heavy process of post-production seem to call for your attention. The colours and shapes that bleed into each other look like they want to escape the frame that encloses them and claim their own right of existence. But that’s still just an interpretation.

How did you become interested in photography?

I’ve always been—since I was 12, I’ve had a camcorder and I used to film my sister. I’ve always liked illustrations, photography, and graffiti; just graphics in general. I was very bad at drawing and painting, so at a certain point I stopped and picked up a camera, because I got more pleasure out of it.

Then, later on in your process, you made your photography more graphic with retouching it in any way possible.

I started doing classic photography, but I was dissatisfied with the presentation. At a certain point during university I realized I was doing the same thing over and over. So, I looked at how I could change the way I worked. I started to play with different physical tools, like printing machines, glue and chemicals, to develop my own technique.

Fotomuseum Winterthur, 2019

When did you discover your signature technique of using plastic in combination with chemicals?

So, basically, when I had this idea, I had made a mistake—in fact, all these techniques are build on mistakes. It took me two years to develop it, after doing things wrong again and again. The first step was when I wanted to print a regular picture with an inkjet printer, but I used the wrong side of the paper. So, instead of using the printable side, I used the backside, which is made out of plastic. It didn’t look good, it was all drippy, but it inspired me to look for a different type of material, which would achieve a similar effect, something that would mimic this.

Why are you so driven to push the photographic medium to the limits of its possibilities?

Today, everyone’s a photographer with an iPhone. Of course there are people, who can use the traditional medium to their advantages, but that’s not the case for me. I want to escape from it, to have my own writing when I use this tool. For me, photography is the first step of production, similarly to, lets say, a pencil when you draw. You have the initial materials, but if you keep it like this, you keep it simple. When you try to expand it, to push it into some other medium, like sculpture or painting, it’ll become more hybrid. Nowadays, you have to work with hybridity, and for me it makes sense to go into this direction. I also like the fact that you lose reproducibility in my practice, which is something inherent to photography. Each piece is unique; so, in that aspect, it’s similar to paintings. But, in another way, you can grasp a piece of reality, because you use a sensor, a shutter, lenses, it’s in a blurry in-between zone.

What’s your favourite memory from your Japan trip, which is also behind your series “In Bloom”?

I once ended up at a crazy party in a forest nearby Osaka, which was really fun. It was huge, while these types of communities in Japan are normally really small, not like in Europe, so I was really surprised. All the installations, the music; they’re really creative with their hands and build these constructions for one night. Everything’s simultaneously really organized but also improvised. I was the only foreigner in this big crowd, so it was a really special moment.

Sounds really cool! Your work has a psychedelic aesthetic, but what are the deeper connotations regarding some kind of psychedelic reality?

I think [the experience of] Japan itself is psychedelic, without taking any drugs. It’s like Disneyland, in a way. That was the point of making this book and not just snapshots. The city is itself psychedelic and organic, even though it’s made out of concrete. There’s a weird “micro” and “macro”, it’s like a cell of the human body. A kind of mysticism—also present in my work—that gives off an organic feeling and can be found in psychedelics.

In Bloom

Your work is pretty surreal, do you personally feel the need to escape reality in some way?

For sure, for sure… I’m a documentary photographer. [Chuckles] Although, there’s no hidden meaning behind escaping something. I’m just making visuals. Of course, as it’s based in photography, there’s a glimpse of reality. But the idea is just to produce stuff that relates to what I feel and what interests me. I want to explore areas for some subconscious reason and then I find solutions to how I want to materialize my experience, with my tool being extended to photography. It’s a translation of what I want to say visually. There’s not any kind of “actual” escaping from reality.

That’s interesting. I’ve read that others refer to your work as trying to escape reality.

It’s difficult to write about my work, it’s easy to make some quick conclusion about something I don’t mean. Only a few people understand what I do. In a way, my work is charming, it’s aesthetically beautiful, but that’s something that occasionally makes it simpler than it actually is.

Your work can also be pretty chaotic, how does it relate to society?

My work does have something to do with chaos. You lose a traditional point of view; there’s a kind of mess and destruction. Chaos is part of nature, that’s how everything works—without rules. We humans try to have control, but it should not be controlled, it’s almost a mystic question within photography.

Notifications