Don’t touch my freedom, it’s for my using only

How do you write about an icon? Resisting a coherent introduction, MICHÈLE LAMY is an uncontainable force — a shapeshifter who has worn the roles of lawyer, cabaret performer, boxer, Rick Owens’ muse, cafe owner, jewellery and furniture designer with equal ease. She’s lived a thousand lives, her every reinvention marked by a singular magnetism. This rainy Paris afternoon, Lamy appears utterly unfazed by the opinions of others, her focus firmly on speaking her truth.

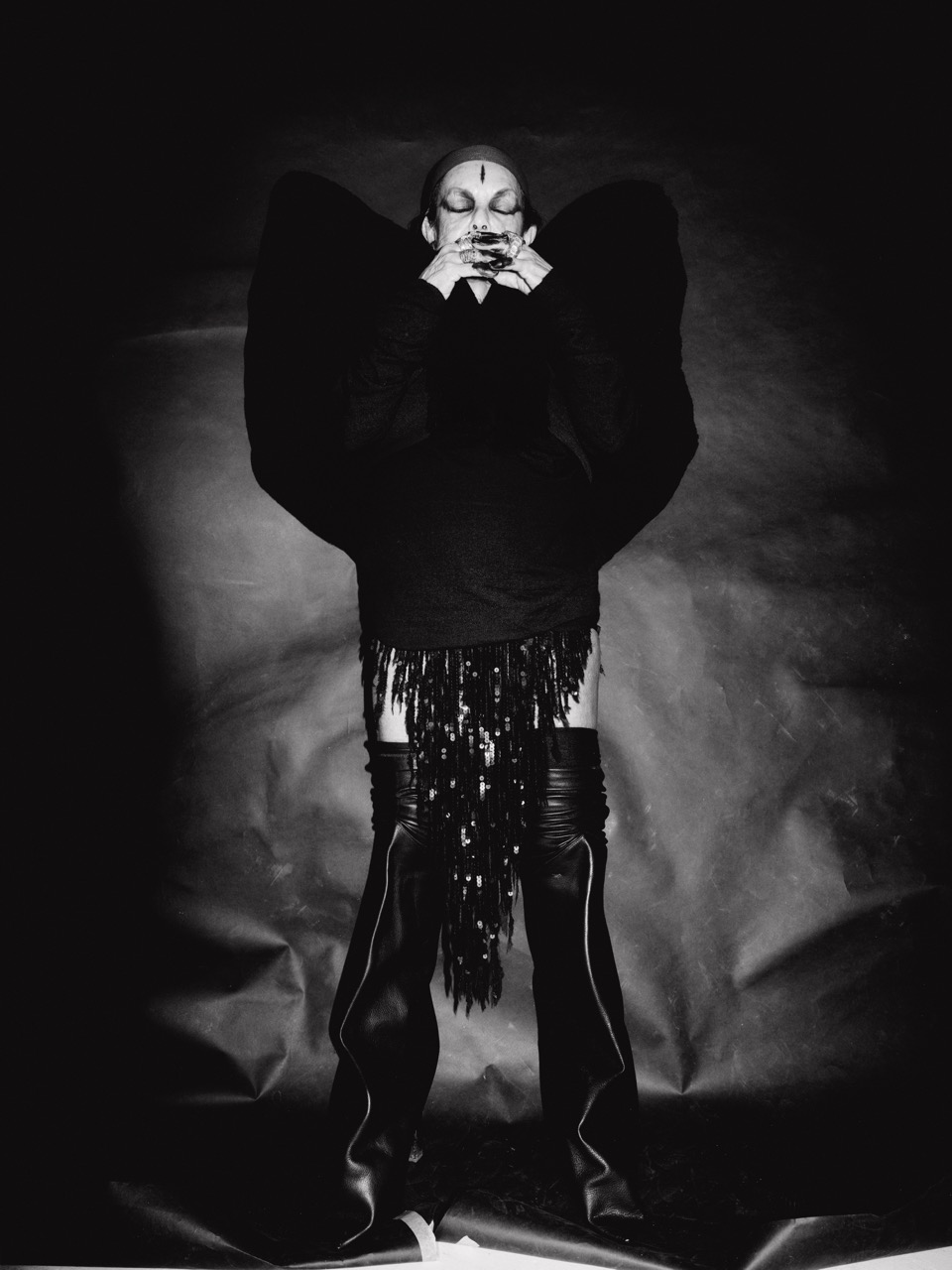

Catching up over lunch, and many cigarette breaks, Lamy talks with disarming warmth and undying curiosity for the world around her. With her stained fingers — a nod to her Algerian heritage (and not Satan-adjacent cults as many Instagram haters might suggest) — and her trademark stack of jagged silver rings, Lamy sits in front of me, embodying a paradox: a figure at once grounded and otherworldly.

You’ve been making your presence felt everywhere lately. What’s on your mind these days?

I don’t know if it’s on my mind or my voice, but lately I’ve been accepting — almost provoking — to do interviews with what is called “the fashion press.” It seems that now only this press is going to be the free press. That’s the only way I can have more of my voice heard about what’s going on in the world. Two days ago I was at the British Fashion Awards and I was giving the prize for Cultural Achievement to A$AP Rocky, who I have known for a very long time and whom I dragged into the art world in a way. In that talk at the awards, I could just speak more freely, the way I do on my Instagram. I know our voice counts. I think if we are the celebration of image and culture, why shouldn’t it also address the pressing issues of what’s happening in the world? We can do more. I didn’t think I’d be 80 at the time there is a genocide.

All art forms go hand in hand with social commentary, in a way. Seeing how restricted many media spaces have been, it’s so special to be able to say whatever you want.

But actually, how did you decide on this feature? I remember collaborating with you for the Skateroom project, but why did you invite me to work with you again? And why for this issue?

We were drawn to the idea that creative expression can serve as an armour — protecting what you believe in while amplifying your voice and those who stand alongside you. Your ethos and approach to art very much resonated with that.

Yeah, because what are we fighting for? You need one of those [she reaches for a stack of the What Are you Fighting For? rubber bracelets on her wrist, and passes me one].

Thank you!

I started this with Overthrow, this boxing gym. What Are We Fighting For? became a big event that was in 2018. It’s when Selfridges gave me the corner store they’d just rebuilt to express what we are fighting for. We turned the space into a boxing gym with a little ring and all the high-end couture houses around it. We worked with charities but the mission was still quite general. Now we have to be even more specific about what it is we’re fighting for. For Lamyland, I was interviewing people there during Covid, but now it’s the reverse – I answer questions instead of asking them.

You’ve never shied away from speaking your mind. How do you navigate institutional spaces while preserving your uncensored voice?

With many art spaces or mainstream outlets like Vogue even, some words — like “genocide” — seem unspeakable. I was at the opening of Nan Goldin’s exhibition in Berlin last week. When she came on stage, she asked everyone to turn off their phones for a minute of silence for Palestine. And then she said, “Germany, wake up!” It was so gorgeous, and everyone exploded in support. Then the director came on stage (I will not say his name) and said he disagreed. He couldn’t go further because the crowd wouldn’t have it. It was good that there were no police, no dogs, no violence — she was protected and able to talk. But can you believe it’s a time we’re surprised that there wasn’t more anti-reaction to what she said? Everything is turning. It seems that nobody wants to know the full story.

Absolutely. I imagine it was a very powerful moment.

There is always a time for a wake-up call. I was born at the end of World War II and have seen the Vietnam War as a US citizen. I come from the generation of “never again” — my parents met in the Resistance. After that, they had been bringing a lot of hope and help to others. Of course, it’s not like life is easy. But we can all help each other to be happy. So why don’t we? You ask me what is on my mind, there is a lot on my mind…

To rewind back a bit, I’m curious what initially drew you to boxing. In the spirit of resistance and action, was it something that offered an emotional release?

Boxing entered my life around 40 years ago. There is something about coordination, discipline, looking people in the eyes. It was also an inspiring time. There was a woman — from Amsterdam, in fact — Lucia Rijker. She was the first woman to compete with men. And that changed the game. To me, it was changing the world, just being a part of it. It was also a sport that got a lot of people off the street and invited the kids. Besides, there is also all that glamour and cinema in the championships. And just the way it encourages you to be confident in your own body. It’s a noble art, it says something.

And do you still practice?

Not as much. I used to box daily, but now, with all my travels, it’s less frequent. It’s also harder to find real boxing clubs in Paris where people hang out, because many have been pushed out of the city. But the essence of boxing, the connection with people, remains with me.

Speaking of your travels, you’ve been on the move a lot recently. What have you been up to?

I’ve been on tour with Travis Scott, designing his backstage space. He is very interesting, and he brings a lot of hope. Somewhere, Travis and I have the same fan. He has more than me, and they are all under 30! But I think it’s important for them, because they are not in the system, and there is a hope to build another world. Ye kind of started it, and I think all those artists found a great way to communicate. They tour with no borders, they go everywhere.

What does hope mean to you?

Deleuze was talking about the big rights of Americans, and how much strength people would have if they saw the world that is bigger than them. That’s exactly what I think hope is. We can’t explain, we can just feel. The hip-hop artists like Travis and Ye are the poets of today. They put art, music, and fashion all together. We don’t need so many museums, we need to bring culture in the arena with the public.

Couldn’t agree more. With your busy schedule throughout the many lives you’ve lived, are there any rituals or practices that ground your sense of self?

I’ve been doing this line on my forehead for at least 40 years, every day. And now I tattooed it underneath. It equilibrates my brain. I also have the rings of course. They’re not the same, but I started wearing rings when I was around 14 years old. I like to wear things that make noise — they’re my instrument. In that, there’s been some consistency in the way I am.

I imagine there’s also a constant presence of tactility and weight — objects that may be foreign, yet become an extension of your body.

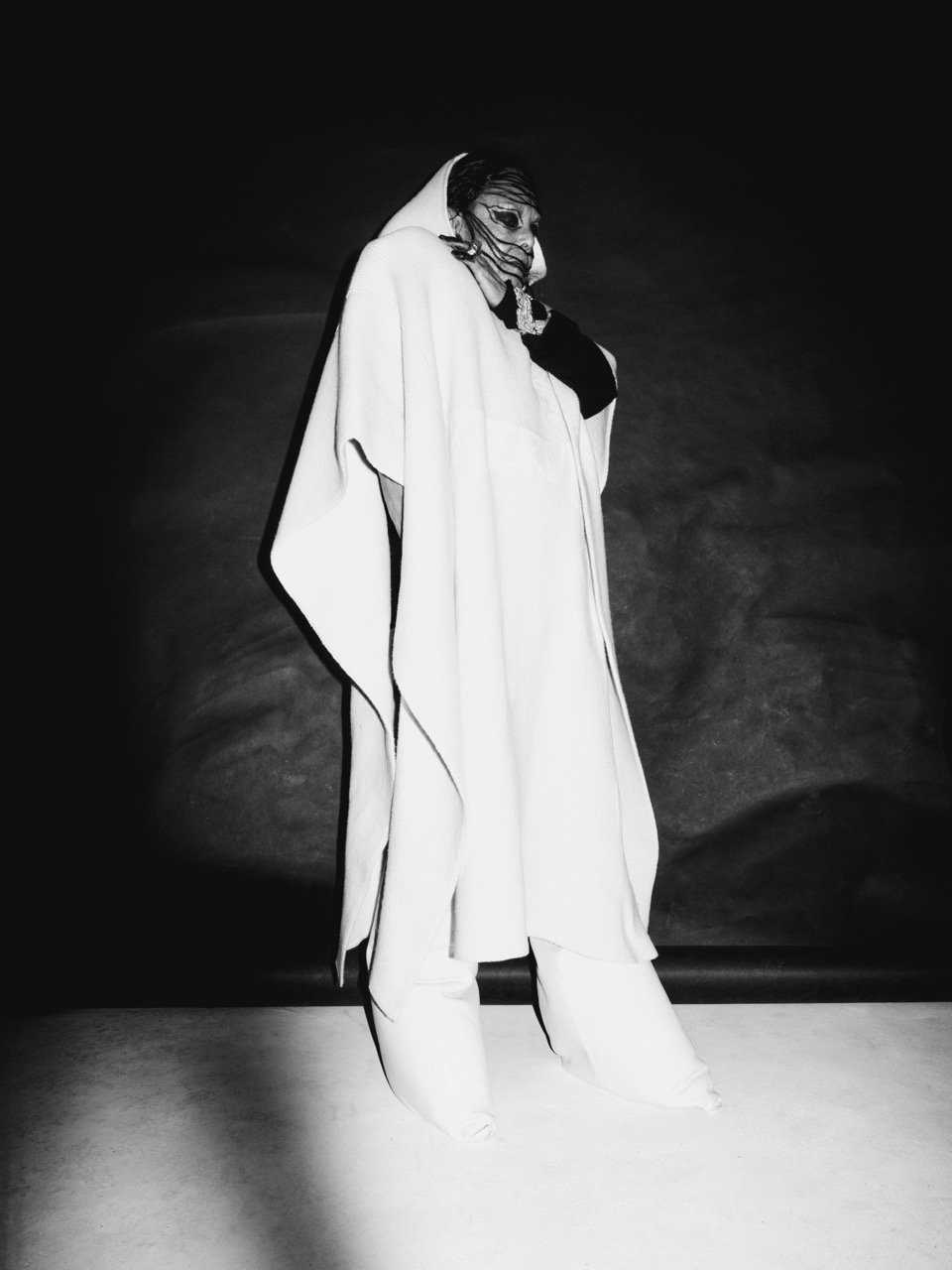

Everything is sensual and physical. I also have tattoos on my fingers because I can look at them. I couldn’t ever understand somebody with a tattoo on their back. I always create a story around what I’m wearing. I connect it to a nomadic lifestyle — nomads have everything on them. There is this romantic image that I could disappear from wherever, but still live on.

As long as you have your rings —

— I have it all. I have my home.

When it comes to your personal style, artistic practices and even furniture work, there seems to be a pull to materials that are raw, earthy, stark, almost elemental. What is the connection you feel when working with them?

This is something I have in common with Rick Owens. We started the furniture collection because we wanted to create things for our own house. We moved to Paris with nothing, really. We started with making things from plywood, which is typically used in construction sites today. But we use it like it was the 17th or 18th century — crafting pieces without nails, everything fitting together naturally. I don’t really know how to tell you. It’s just about things that are raw — finding something on the street, recycling it, and making it into something extremely beautiful.

Seeing the potential of what something can become is such an art in itself.

Exactly. We use wood dyed in the 80s, and we found places that stock a lot of the leftovers from back then. There is also understanding of the materials. For example, everybody tells me not to use wood. But no! There was this designer, Philippe Starck, who started doing all-plastic furniture in the 60s to save the forest. It’s completely wrong. The forest needs to be treated in a sustainable way. The deforestation happening in the Amazon is terrible. But there are indigenous artists and designers who make furniture with the woods from the Amazon, just to show people can live with the forest instead of irreversibly cutting it down for oil or industrial materials. There is some fight about it.

I suppose it’s about learning to live with your ecosystem, not separate from it.

Exactly! It’s so fake what people say sometimes. We could promote any narrative because of the Internet, but we all must learn our history. There has never been so much information available to us.

Yet this infinity of information often still doesn’t help.

Yeah, we also used to say that if there had been the Internet, we would never have concentration camps. But now it’s right in front of our eyes, and we wake up every morning to seeing the news and not being able to change a thing. So, figure that out. Perhaps, it’s the end of the capitalist system, I hope.

It’s about time. How do you envision the future?

We cannot go back to running in the woods, but we can look at our past civilisations. I tend to always go back to the Egyptians — the interesting thing to me is that there were a lot of gods. Everybody could have their god. And they achieved so much, not fighting between whose god is the best. For us, religion has been a big problem. Like in Catholicism, the people who wrote the thing about Jesus, they were not there.

The Bible was written a lot of time after. And the same for Allah. He was long dead before anybody wrote the Quran. But then we all relate to them, and not to the ones who wrote it. They were all a little drunk that day or something. I’m at the stage of my life where I have to know the future, because the next moment is the future. I have grandchildren. And I have the world around me that I cannot imagine. So which kind of hope are you looking for? Do something. What is great is to have love. To do things with pleasure, to express ourselves, to connect…

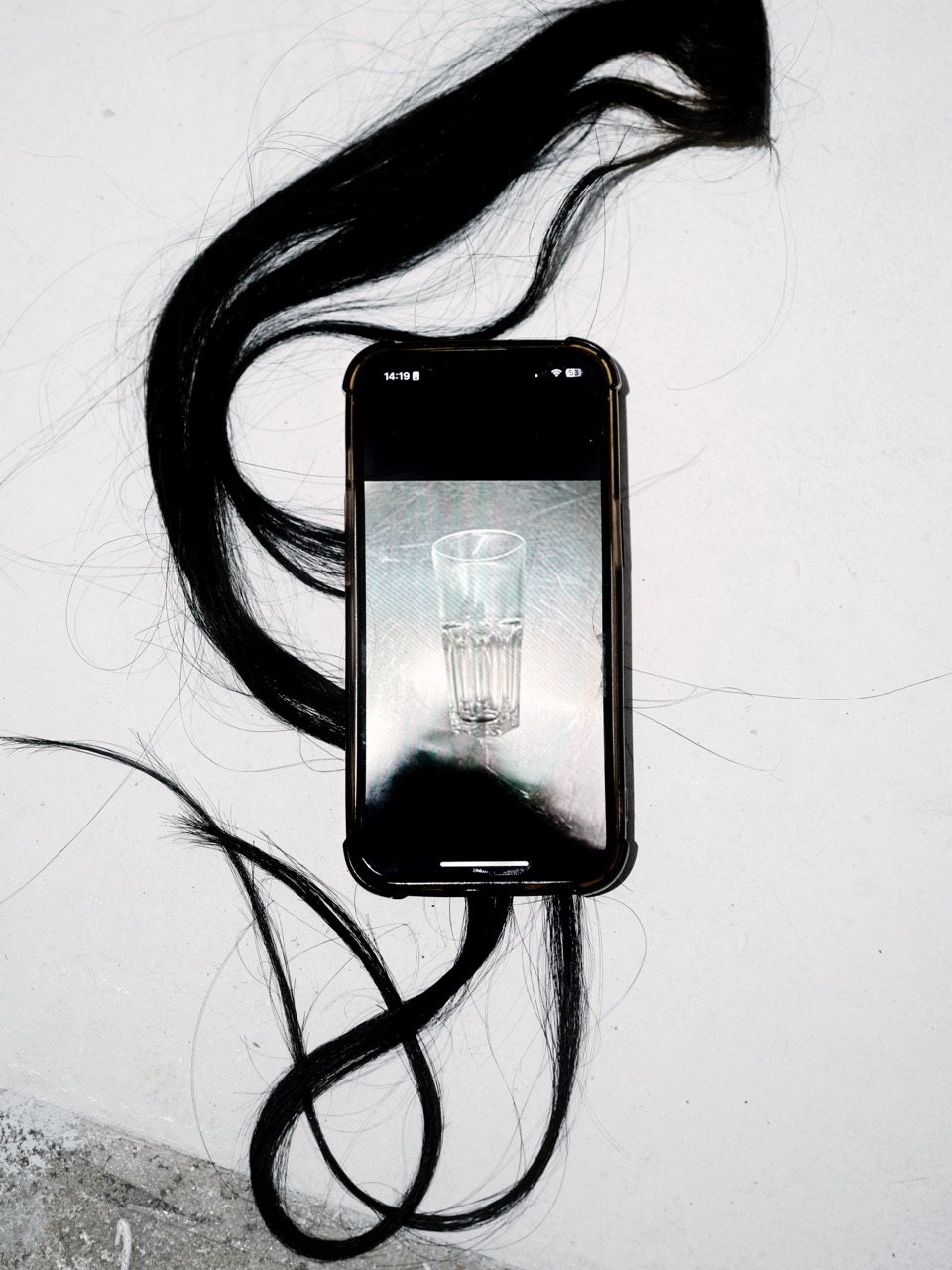

On a lighter note, I was intrigued by your rider — grapes, plain tortilla chips and a glass of water is a very humble request. What’s your favorite food?

Obviously, it’s not what I just ate now [no shade to the plate of food Michèle set aside]. I asked for snacks more for the team — I don’t go to shoots for food. But generally, I like a lot of different foods. I love Japanese food, but it’s a bit hard because Rick cannot stand it.

Oh no, I’m so disappointed in him! Do you have any guilty pleasures?

Why would I be guilty about something that is pleasurable?

Good answer. What is something you wish people asked you more?

Everything I was talking about in the beginning. I like to talk. But I’m really choosy, and I always try to find the right people to express my voice. And I don’t answer what I don’t want to answer. There are so many things to talk about, but sometimes people can send you questions in advance and it’s the same thing. You were not the case.

That’s an honour.

I think right now, we have to express ourselves in a way that will help each other, and show that we’re not alone in how we think. And that’s something we’re doing.

Words by EVITA SHRESTHA

Photography by WALTER PIERRE

Styling by MICHÈLE LAMY and REGINA NTAHOMPAGAZE

Hair by DALIBOR VRTINA

Make-up by CATALINA SARTOR

Creative production by PYKEL VAN LATUM @ Glamcult

Styling assistance by ERINE LUNA HAMOUDI and ANAÏS PANIZZI

Make-up assistance by VENUS HERMITANT

Production assistance by VERONICA TLAPANCO SZABÓ and VIKTOR DIMITROV @ Glamcult

Notifications