“We’re reclaiming the right to softness, to intimacy, to love that doesn’t require justification or performance. Queer romanticism is no longer a contradiction — it’s a form of resistance.”

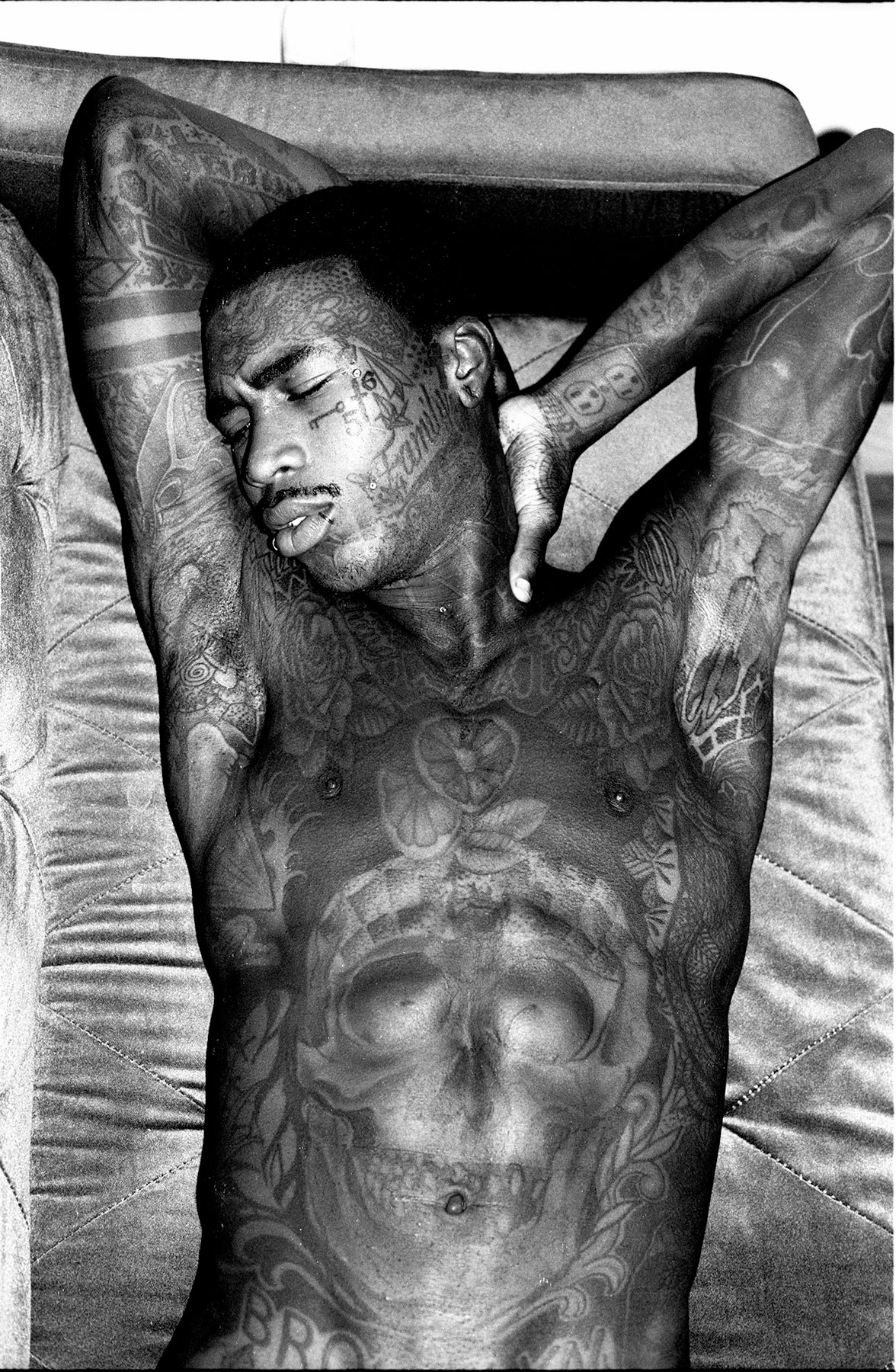

Image by Slava Mogutin

Do you ever fall into a rabbit hole when reading someone’s biography online and think to yourself, how the fuck are they so cool? Slava Mogutin and his life story pertain exactly to that kind of encounter. Russian-born & an ace of all trades, he did it all before we could even gather our thoughts around what it may even be. Starting off as an agitator of the post-Soviet somber stance on queerness, his courageous existence did not fail to draw the “malicious hooliganism with exceptional cynicism and extreme insolence” claims from prohibitive media outlets – attracting not only severe scrutiny, but legal charges and a close call to imprisonment. Soon after the environment started feeling too stifling, his subsequent exile in New York propelled his high-yielding body of work. From his acclaimed words, poetry, and Russian translations of Dennis Cooper and other cult classics, the drastic change drove Mogutin toward the visual. Be it the flippant imagery of Lost Boys or the hidden underworld of NYC Go-Go, his photography beckons us into a world we feel both prohibited from and viscerally curious about. His newest project – My Romantic Ideal – does not stray from the magic, but changes its angle as Mogutin ascends from the role of its sheer creator into its curator – comprising 28 queer artists folding across 3 generations and 14 countries. So instead of entering his own world, we are guided into it with him on our side, like following a leader on a pilgrimage.

We caught up with our kingpin for a dissection into what the elusive romantic ideal even is – commencing into a world of lust, the politics woven into it, and the sacredness of the queer body.

It’s becoming less so now, but romanticism used to be quite a controversial topic within queer communities – I’m talking about endless discourse against hetero performativity, or at the end of the spectrum, the full rejection of romanticism as a form in itself. How do you feel about its evolution?

I don’t think there’s anything controversial about queer romanticism, but perhaps it has been trivialised — either as heteronormative fantasy or nostalgic kitsch. For many queer people, especially those of us who came of age in hostile environments, romantic longing was inseparable from danger, rejection, or exile. But I think there’s a powerful shift happening now. We’re reclaiming the right to softness, to intimacy, to love that doesn’t require justification or performance. Queer romanticism is no longer a contradiction — it’s a form of resistance. The queer body is both a site of desire and protest.

How do you see (queer) love in relation to lust?

For me, they’re inseparable — twin flames that feed each other. Lust is often the spark, but love gives it meaning, depth, duration. In queer experience, especially for those of us from marginalised or criminalized backgrounds, desire has always been political. It’s about visibility, dignity, survival. Queer love contains multitudes — it can be carnal and cerebral, fleeting or eternal. It’s not bound by societal rules, which is what makes it so transformative.

What was your favourite part of this project?

The most satisfying part was bringing all these artists together. Conversations between three generations of queer creatives from different backgrounds and walks of life. The energy that builds when artists come together and realize they’re not alone in their obsessions, desires, and wounds. Seeing these works in dialogue — across languages, cultures, and generations — was like watching a constellation form. There’s magic in that.

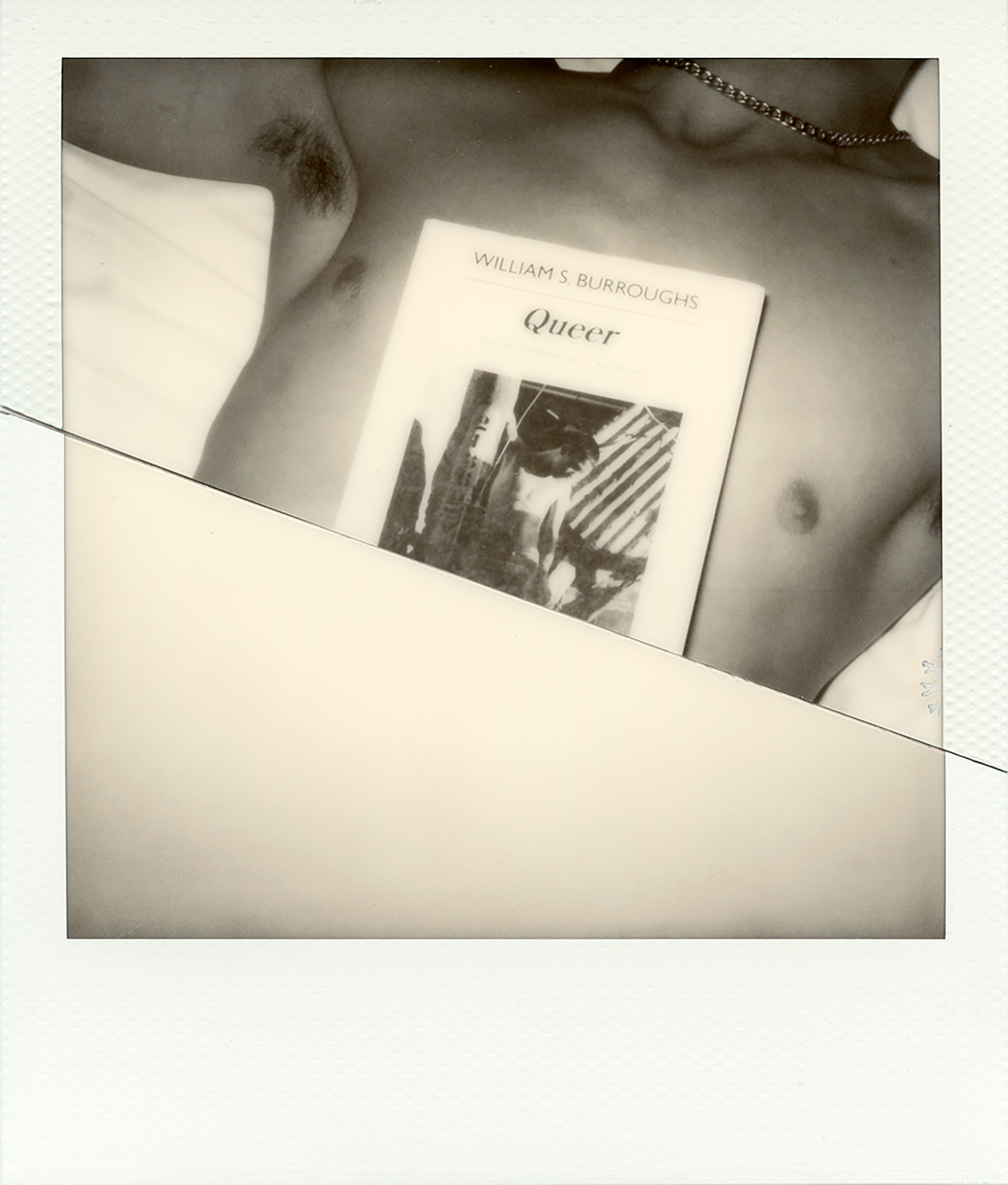

Image by Paul Mpagi Sepuya

Do you have a favourite piece?

That’s a very tricky question for a curator. It’s like asking a parent to choose a favorite child. Each piece carries a story, a soul, a unique voice. Stanley Stellar’s beautiful vintage print of a couple kissing in the sand on Fire Island. Tom Bianchi’s recent handmade objects are very interesting in terms of blending mediums, including photography, painting, collage and sculpture. He’s one of the pioneers of gay photography, and it was an honor to have his new work in the show. Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s pieces are stunning in composition, lighting and execution. Robert Flynt’s unique prints on found maps are very intricate and complex in deconstructing male archetypes. Miguel Villalobos’ striking black-and-white nudes. Raw punk photos from Gio Black Peter. I could go on about every artist and work in the show. There are so many fantastic contributions—I’m considering turning it into a big sexy book!

Sweet! What were some things you were confronted with that maybe you didn’t expect?

I came up with the title and idea for this show a while ago, but it took over a year to realize it. It was my most ambitious curatorial project to date, following the success of the shows I previously curated in New York, Mexico City and Berlin. The project I envisioned was more poetic and introspective than transgressive and confrontational. I’m not a stranger to transgression and controversy, but I think we’re all fatigued from identity politics, wokeness and cancel culture. Romanticism is often dismissed as “too soft,” especially now, when we’re being constantly bombarded by images of shameless exhibitionism and narcissism, violence and gore. Rejecting aggression and confrontation is a way of finding peace in the dystopian, fractured and divided world we live in. In this context, queer romance is not a luxury—it’s revolutionary. It wasn’t my goal to curate another all-inclusive queer show that wouldn’t satisfy anyone in the end. So, naturally, I got a backlash from artists who weren’t included, or those who criticized me for not including lesbians, trans and nonbinary artists, as well as bears and plus-size models. Of course, they’re missing the point…

Image by Ross Collab

So what is the point then?

My Romantic Ideal was never about ticking boxes or trying to please every demographic. It was about curating a cohesive, personal vision — an emotional landscape that reflects the ways queer desire, intimacy, and vulnerability manifest beyond the surface of identity markers. The premise was not to represent every letter of the acronym, but to open a window into how different artists reimagine romance through their lens—honestly, poetically, unapologetically. What surprised me most was how polarizing that felt to some people. There’s this expectation now that every queer project must function like a committee, a census, a representation report. But art isn’t bureaucracy. It doesn’t work like that. And if it does, it fails. The power of this exhibition came from its refusal to cater to those pressures. I chose artists whose work spoke to me on a visceral level—people I trust, whose vision has integrity, who’ve lived through real love and real loss. That kind of work doesn’t ask permission to exist, it commands presence. At the same time, the show had an incredibly warm and emotional response from the public. People told me they saw themselves in the work—not as slogans or symbols, but as lovers, loners, dreamers. That’s the magic of queer romance—it doesn’t conform, it transforms. It’s messy, it’s nostalgic, it’s full of contradictions. And in today’s climate, choosing tenderness over outrage is itself a radical gesture.

What are some of your hopes for the future of queer romanticism?

It’s time to move beyond binary thinking — that romanticism has to be apolitical, or that queerness must always be defensive and militant. There’s radical power in softness, in mutual care, in eroticism that isn’t performative but profoundly human. I want to see more space for complexity — for love that’s flawed, defiant, sacred, and yes, deeply queer. And I hope the next generation feels more free to create without having to explain, justify, or dilute their truth.

Image by Miguel Villalobos

Image by Stuart Sandford

Image by Slava Mogutin

Image by Alejandro Ruiz

Image by Cameron Lee Phan

The show is on view at the The Bureau of General Services – Queer Division in NYC through August 31 – more details here

Images courtesy of the artists

Words by Luna Sferdianu

Notifications