Image by Tobias Wendt

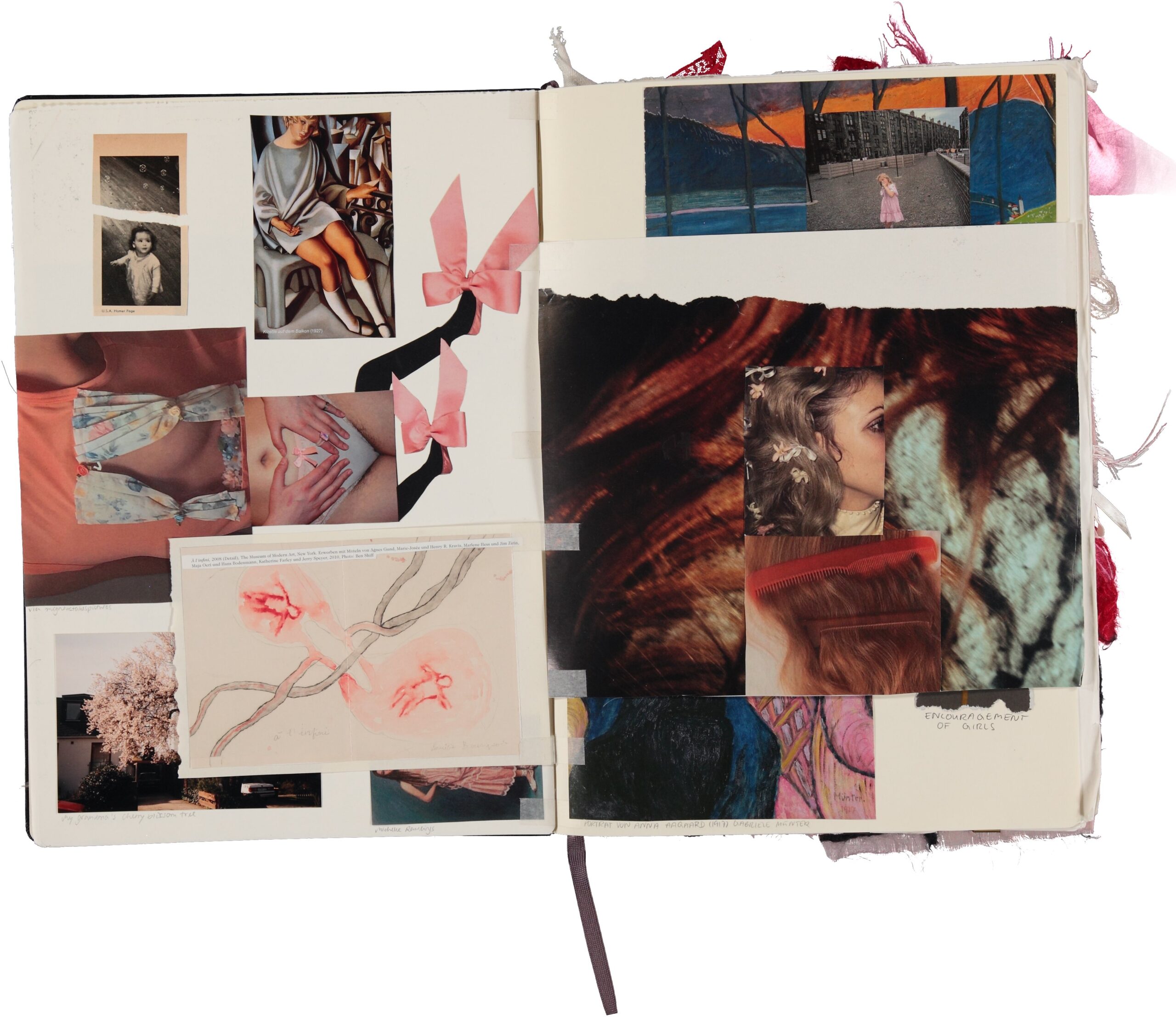

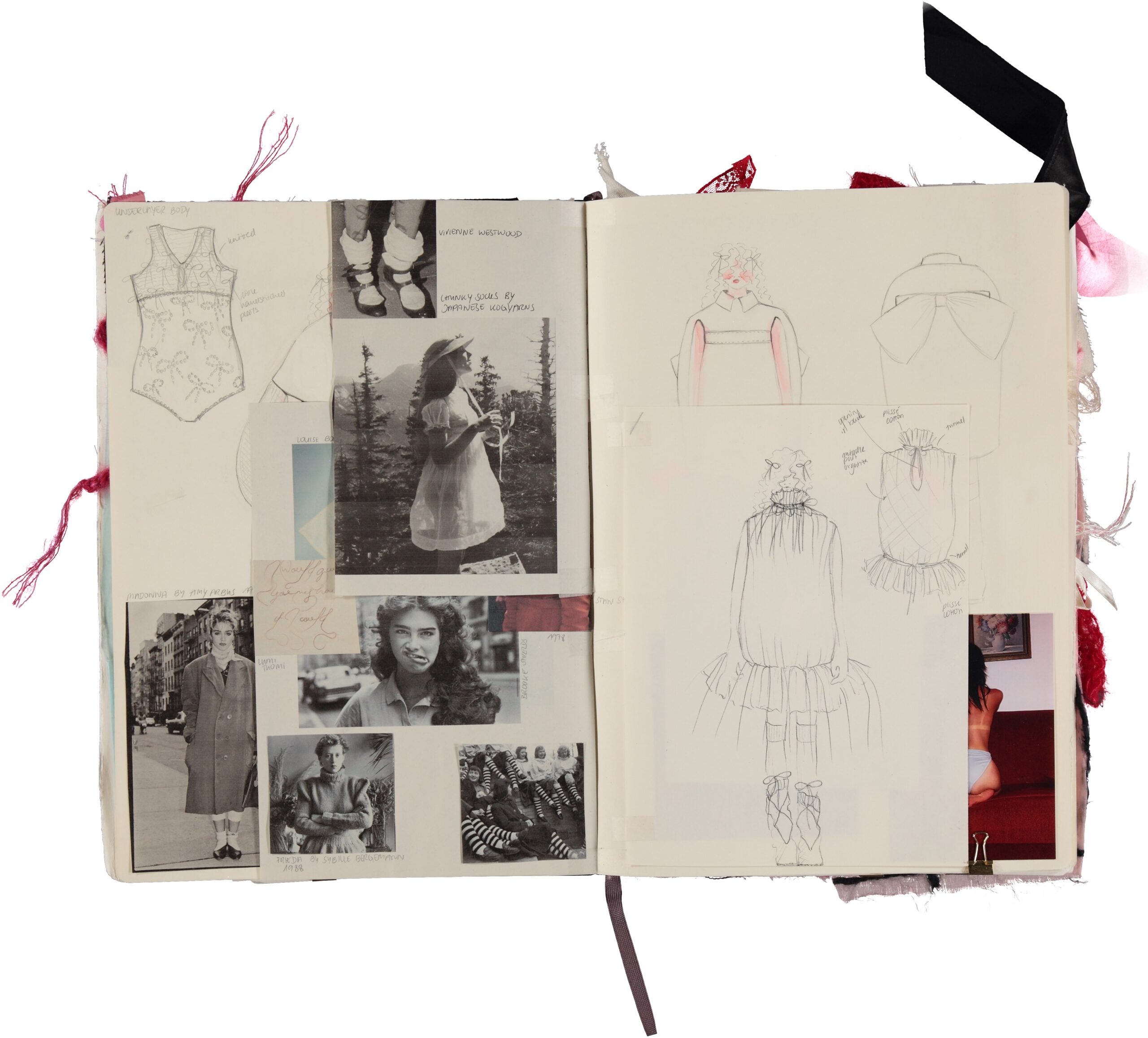

Just last month, she dazzled us with a graduation collection that captures the essence of girlhood in every stitch – Sofia Hermens Fernandez’ designs are as playful and girly as they are deeply theoretical and subversive. With inspirations from Girlhood Studies and Sofia Coppola movies, Hermens Fernandez’ creations are a perfect blend of handcraft and intellect. Sofia uses elements like bows, knitting, and felting to craft pieces that are both girly and strong, unified by shades of pink. The aim is to create garments that challenge traditional notions of femininity while celebrating its joy. Her approach is all about storytelling through rich textures and detailed textiles, aiming to make powerful statements on identity and femininity.

Hi Sofia! Congrats on your graduation collection! Loved seeing your looks during the show and the expo. Can you tell me everything about ‘Semiotics of Girlhood’?

I’ve always been very fascinated with the concept of girlhood and the aesthetics around it. We all seem to have these images around what girlhood looks like. The signs around girlhood are fun to play with. On top of that they are very much tied to fashion and textiles and handcraft.

During the year between BA and MA I thought, why not write a thesis at the Academy and dive really deep into this topic so that I really have this theoretical research background? And then I could give my own take on the things I have discovered, with my collection afterwards. Once I started designing I really had the feeling that I had constructed this own world , backed up with so much research. It was quite clear from the beginning that bows would play an important part in the collection. I wanted them to actually create the silhouettes because I didn’t want to use them too much in a decorative way. In fact, they’re just knots if you think about it – but we have this immense world of semiotics around bows, which is very fascinating.

And how did you put that into your collection visually?

I think my general approach for the collection was to have nice big silhouettes of garments that represent archetypal clothes, like a shirt or a coat. They were big enough so that there was enough volume to then drape with the bows. I would place ribbons on different parts of the garments and then start connecting them and making the bows, and by that, shaping the silhouette. There was a lot of hand knitting involved, which also made a lot of sense with my research around the education of girlhood. Becoming a girl, at least until the 1950s, was very much connected to learning handcraft techniques. I also used other handcraft techniques such as hand felting and appliqué. I created a lot of fabrics with checks, imitating the Vichy kind, which is a very typical pattern in children’s clothing. I used it mainly in my menswear. The way the lines are felted makes them look a bit hand-drawn, they look a little crooked, as if a child would have drawn them on. I loved playing with these elements.

You said that girlhood is attractive for different types of identities, can you elaborate?

I called my collection Semiotics of Girlhood because I really just picked out these images and signs of girlhood. For a long time, these signs have been quite marginalised, but there is a certain attractiveness to them that we can’t deny. I would say that all kinds of gender identities can like them. I remember still in my school sometimes if a boy would wear pink, people would talk about it. I always wondered, ‘how can it be that it has this immense connotation in people’s heads?’ But then, I did all my research, and I actually understood why. I think right now all these immensely charged elements around girlhood are actually very powerful tools to subvert these ideas.

What was the first time you became aware of the implications of girlhood yourself?

Growing up in general I think we all, as children growing into teenagers, like certain things and reject certain things we liked before. I know from a lot of pictures my mom took that I was this very girly girl. I loved Disney princesses and everything to do with these things. Around the age of 10 to 12, I had this feeling that these girly things I was into were weak and I had to change my style to be taken seriously. And I couldn’t really place where it was coming from because it wasn’t necessarily from my friends or my classmates in school. I started to go more into this soft grunge, dark style. I was painting my nails black. I just had this urge. I had to do something about my appearance to be taken seriously.

Do you feel like being girly wasn’t fashionable at the time?

Of course there were girly elements in the 2010s, but not like the way it is now with this coquette style and other hyper feminine trends. These aesthetics are seen as more interesting in fashion than before, I believe. The 2000s/2010s were all about girls being super skinny. There was and still is all this pressure on girls. I also had a little bit of struggles with eating disorders in my teenage years, even though I came from a very protected household. I didn’t have a big trauma or anything from home. So I was a bit like, where did all these toxic ideas around girls and femininity come from? Looking back now, my fascination with the construction of femininity has drawn me into fashion. Fashion is such a powerful tool in any construction of identity. I am fascinated with femininity, how it changes, and how it gets perceived differently throughout time. And, of course, where women and girls themselves are positioned in the construction of it. Are they active in constructing it themselves, or is it something inflicted upon them? That’s the core question I’ve been concerned with.

Yeah, it’s interesting because the way you’re telling about your childhood, it feels a bit too relatable. I think we might have had the exact same childhood in that sense, haha.

I think these experiences, somehow, can be quite universal. That’s why I was a bit surprised at how little research there is around this, I mean there is this whole field of Girlhood Studies but it has only really started in the 70’s, 80’s… so there is still so much work to do.

And what do you aim for with your collection and how do we see that back in the pieces?

I think for me fashion should also just be about joy. I want the textures to be rich and the textiles to really tell stories, and I hope that the concept of subverting those semiotics comes across. Maybe certain people that are not within this bubble will still think “Okay this is just a girly collection, period.” And maybe that’s okay too.

I understand the pressure, but at the same time I feel like if people like your collection for the visuals without even understanding the concept – you’ve pretty much already won. What were the challenges you faced while working on your collection?

Where to start… in general, you have this very limited time frame to create everything from scratch. This is already a challenge on its own. Then I had a lot of theoretical research which has helped me a lot – but sometimes I felt like I had to prove that I’m intelligent. It’s hard because people will only see the collection for three minutes on a runway. So I sometimes felt like, wow, is it even good enough? Will people see that it’s actually well thought through? I had a lot of doubts around that. I wanted to embrace a lot of different handcraft techniques and with the help of my friends I managed to do everything I wished for. I had the greatest collaborations with fellow creatives and I was working with my mom the whole year, mainly on the hand knitting. Those were also the most fun times because you could just sit there, handcrafting, talking, and being together. So that was really nice this year.

What’s the most important thing that you learned during your four years at the Royal Academy?

I think the most important thing is to trust myself and my intuition, and that difficult situations are always dealt best with humour. But at the moment I’m really still in the process of really processing the whole four years. I still have these weird flashbacks of moments in first year, haha.

Has the school been any different with Walter stepping down?

I still had Walter as a teacher in my third year, and Brandon’s first year was during my gap year. I was in Dirk’s last year in the masters, so I’ve only witnessed Brandon’s influence indirectly, but I’ve known him quite well from before. I do think that the atmosphere has changed a little bit just because he’s way younger and more relatable for students. He’s also still quite close to a lot of students, also some he was teaching. I think that was a little bit difficult, but I guess it’s just a generational thing that will get better just once the years pass. From what people have told me his style of teaching is definitely very different from Walter’s. I know he’s working on a lot of things, changing them more for the current times and with more of an eye for younger generations.

What kind of things were outdated do you think?

I mean, there’s been very big communication issues in the academy. With all these international students, I think it was a little tricky that all the teaching staff were Flemish. Brandon is from a more multicultural background, which draws a very big contrast from the other teachers, some of whom have been teaching for up to 30 years. I believe that his multicultural background helps to understand international students better, especially those who come from far away and had to leave their whole lives behind. For me, moving here from Germany wasn’t a very big deal, but imagine coming from the other side of the world and then being expected to perform extraordinarily in school. Some teachers can lose touch with the reality of what it means for students to be here. Especially in the first year, the teachers have been seeing the same projects over and over again and want to be surprised and see something mind blowing.

I hope students feel more heard now?

Just from what people told me about the atmosphere it generally feels like there is a shift happening. I definitely think it will go in the right direction, but it’s just the beginning, so I don’t really know yet.

Image by Tobias Wendt

Time will tell. Can you tell me a bit about your internship?

Yes, I interned at the Fashion Museum (MoMu). I was in the exhibition and collection department, which was really great for me because I was not directly creating anything myself. I really, really enjoyed it, and it gave me new energy to come back and do this collection, actually.

It’s so important to take a step back to be able to see what’s in front of you sometimes. Who is the designer or brand that inspires you the most and why?

Simone Rocha. She manages to have this very recognisable, signature style. And she manages to have this approach to femininity that is quite subversive. I love her storytelling, which is also very personal since she works a lot with her own cultural heritage. In terms of storytelling I have always loved the work of Alexander McQueen, but I feel like every fashion student says this, haha.

I guess he’s just too good not to mention. Same for Simone Rocha of course – she’s the best. If you had any advice for a younger designer, what would your advice be?

Don’t give up and trust your gut feeling. I know it sounds quite cheesy, but I think it’s so important because we all have doubts about what we’re doing. Also, try to reach out to people you admire. Because in my experience, people are very open to talking to you. You can learn so much from other people’s experiences.

So real! It’s easy to forget that people you look up to are, in the end, just people too.

Editorial images by Tobias Wendt

Portfolio images courtesy of Sofia Hermens Fernandez

Words by Pykel van Latum