In a world saturated with imagery, can art survive as a reflection of one’s own meaning?

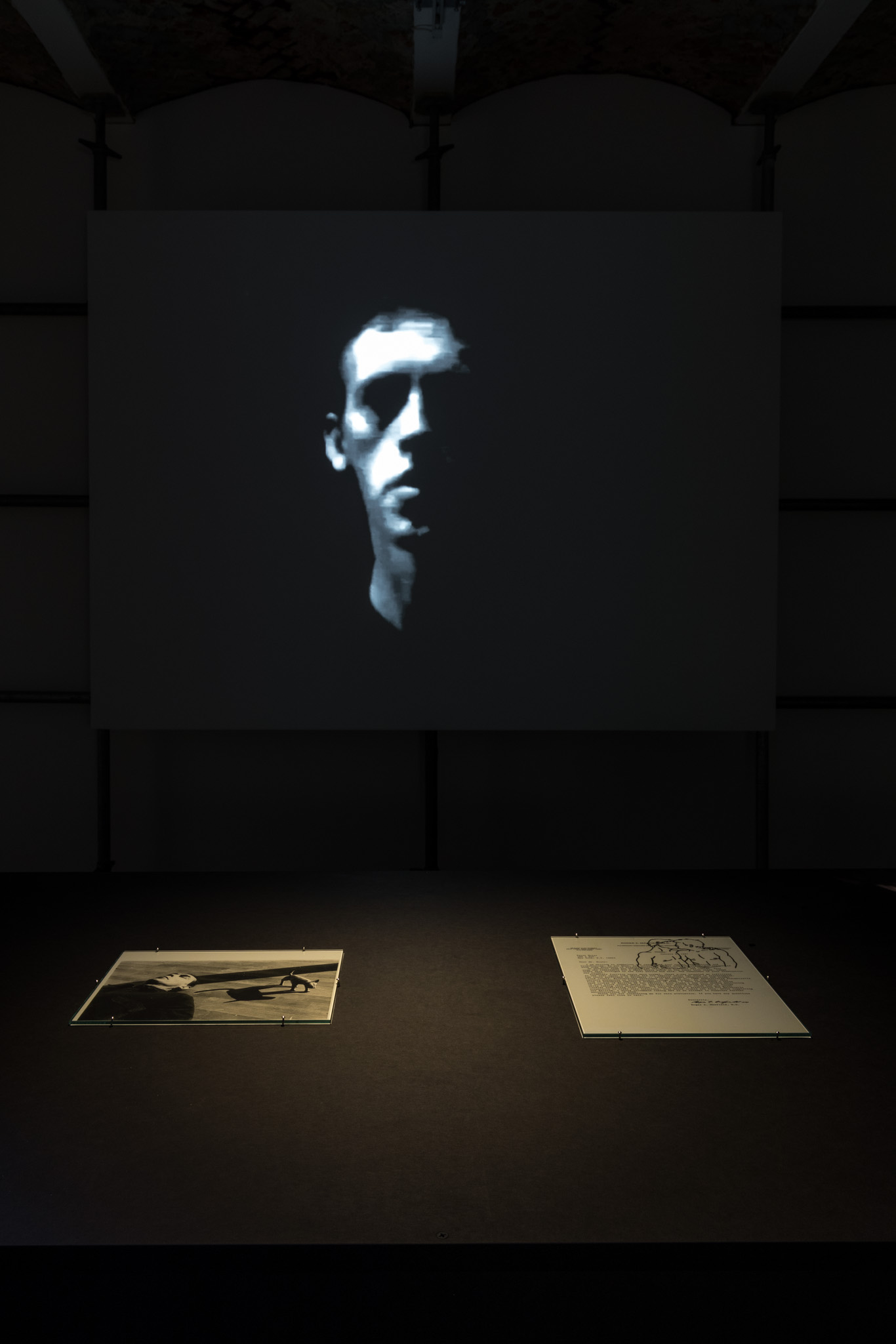

David Wojnarowicz tested life. He didn’t trust it, nor its power structures and the institutions that now pay homage to his life as an artist. As a viewer at the recent retrospective of the artist’s oeuvre at KW, Berlin, I walked through Wojnarowicz’s life. At times, as if I were in a trance, I got completely lost inside his work. Especially when watching the live multimedia performance of his work ITSOFOMO (In the Shadow of Forward Motion), which was performed by Ben Neill and Don Yallech inside the KW exhibition hall over Gallery Weekend. At other times, as I walked from image to image, I questioned: Why does this man, whose life had some similarities to my own yet occupied more spaces of the “Other”, touches me more than my own contemporaries can at late. I came to some semi-conscious conclusion through one of Wojnarowicz’s films, Inside this little house, 1989.

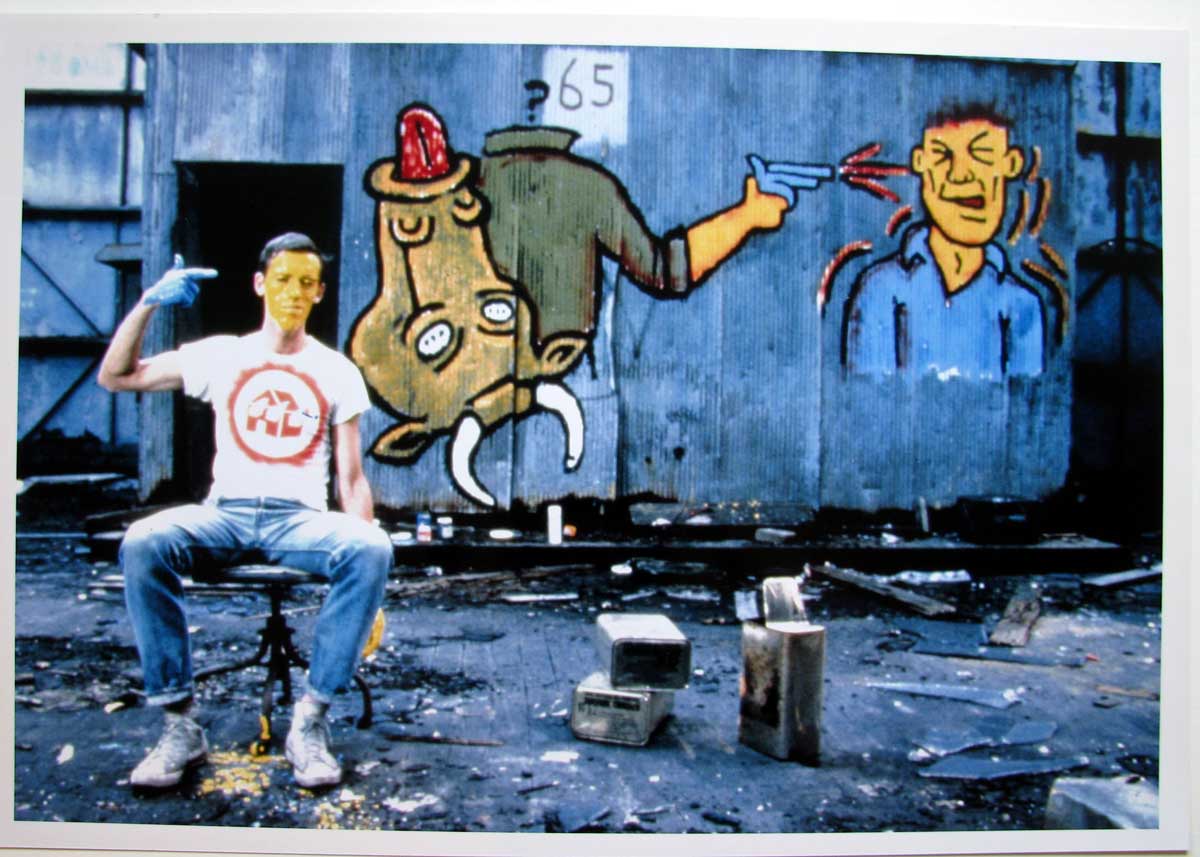

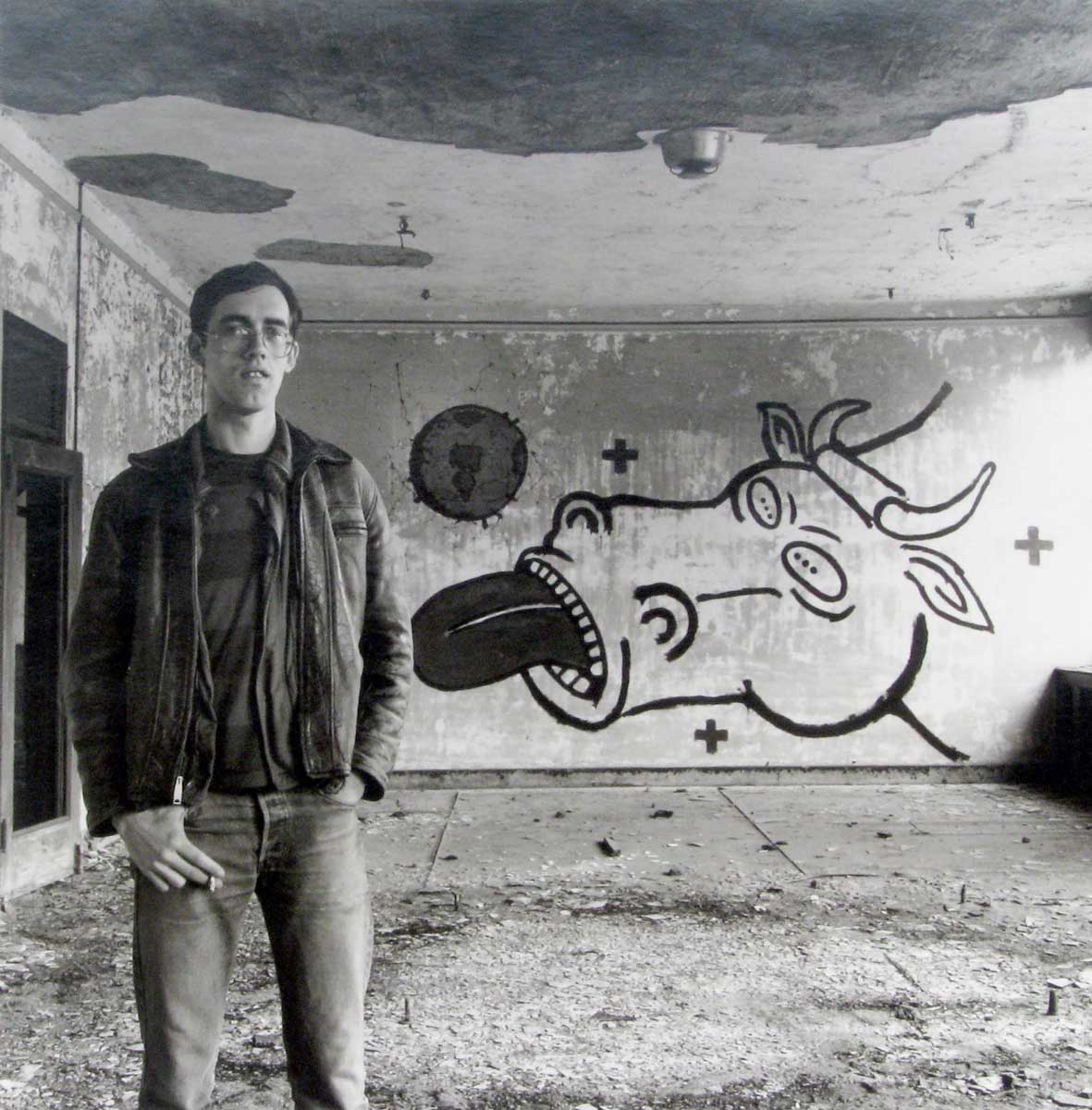

This particular video is situated in the corner of the exhibition, subtly withdrawn and depicting a cardboard house on grass, smoke pouring out of the windows. As Wojnarowicz supplicates the moving image with spoken word formations, lead stones appear in my stomach. “Sometimes the interior of this house is the universe” he announces. This is the third time I’ve been inside this exhibition and, at times, I still feel like I’m the only person inside the room. This little house on fire that he speaks of is an understated recurring motif that the viewer frequently finds throughout the 150 works on display at KW. It appears on Wojnarowicz’s chest via his iconic DIY stencilled t-shirts or on broken and forgotten walls that were his version of white cubes, on which he imprinted this motif. And it is this little burning house that keeps drawing me to Wojnarowicz’s work, while flashes of a half-forgotten quote trail through me; something about the fact you only notice the limitations of a house’s design when it’s on fire. Is the reason why art touches us less and less a result of its wish to be accepted into this burning house, to be immortalised inside this tomb?

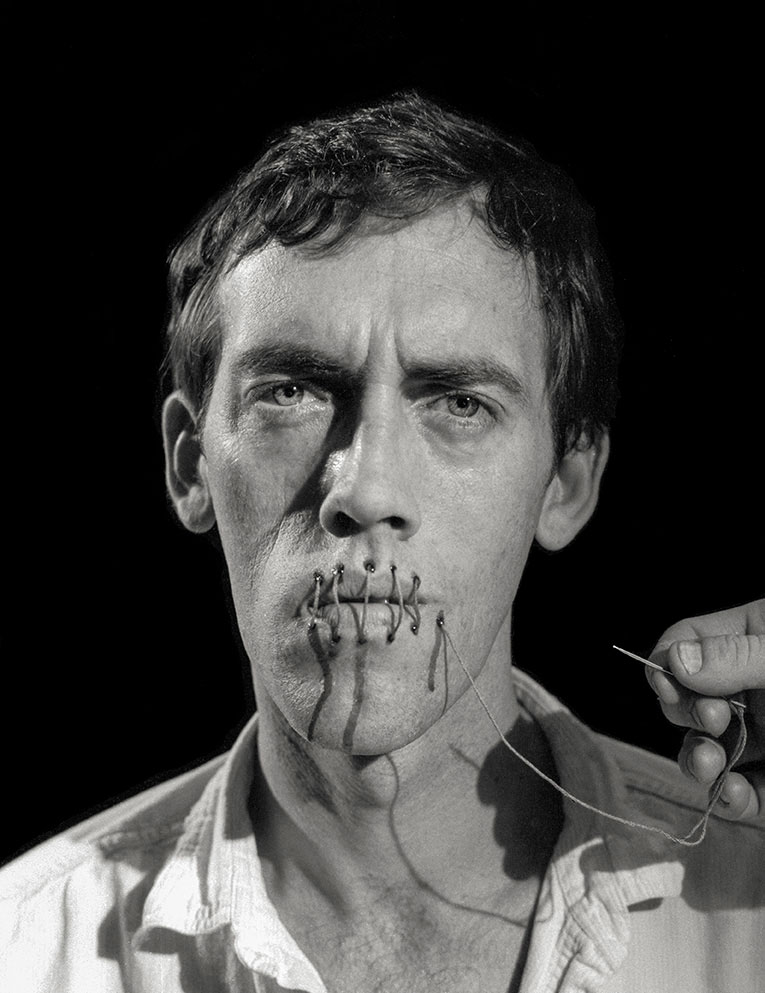

To grasp the magnitude of this question, let’s briefly go back in time. Wojnarowicz emerged as a multi-media artist in the ’80s in the East Village. He was a relative outsider to the traditionally schooled art careerist and instead found his artistic form with his peers. Collaborators and friends such as Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Peter Hujar and Ben Neill, amongst others, play strong roles in his practice. Wojnarowicz was as much a writer as a visual artist, and, in a way, the visuals he creates and the words he speaks open up his work to the viewer in generous floods, which are not easily digested. In fact, they’re deeply personal but, in some respect, seem to apply to all. His metaphors are lucid and domestic. When his half-flickering face delivers a monologue to you, it feels as if he’s speaking both to you and for you. He unpicks all the thoughts you have wrapped up in your mind-tongue and explores them as succinct vectors and pathways. In one of his most iconic images, blood runs down his chin like ice cream or cum. Titled (silence = death), 1989, it was created with Andreas Sterzing and was also one of the famed slogans of the ACT UPmovement battling AIDS. The image portrays the artist with his mouth sewn up, another hand appears to be holding the needle as Wojnarowicz stares out at you from the frame. At first, it appears as if someone else, Sterzing perhaps, threaded this needle through his flesh, but David’s eyes don’t allow you to be certain. This is the position I admire in Wojnarowicz’s work the most—the fact that nothing is binary, that blood could drip like cum. The fact that we should be suspicious and not accept anything, not even a photograph of the artist himself as something that’s blatantly obvious. From him and his work, we learn to question everything, especially our own eyes.

Various citations in art history declare that Wojnarowicz became political after the death of his former lover, friend and mentor—the renowned photographer Peter Hujar, who lost his life to the AIDS crisis in 1987. This led to a majority of Wojnarowicz’s work to be read through this lens of history, especially as he was himself diagnosed with HIV and later died of AIDS in 1992. Yet, this was not the only fight the artist had in his life. He also fought various legal suits that declared his works to be sacrilegious, pornographic and depicting hate speech. Over the course of his life, Wojnarowicz fought for, and with, words and images from a personal and political space of uncertainty. His works are often hostile and harrowing, he uses anger and fetid hope just like other artists pick up ready-made materials. He’s undoubtedly a unique voice, but also one that could translate the noxious aspects of living into art. This is a rare feat and, seemingly, one that’s becoming rarer and rarer inside the gallery space.

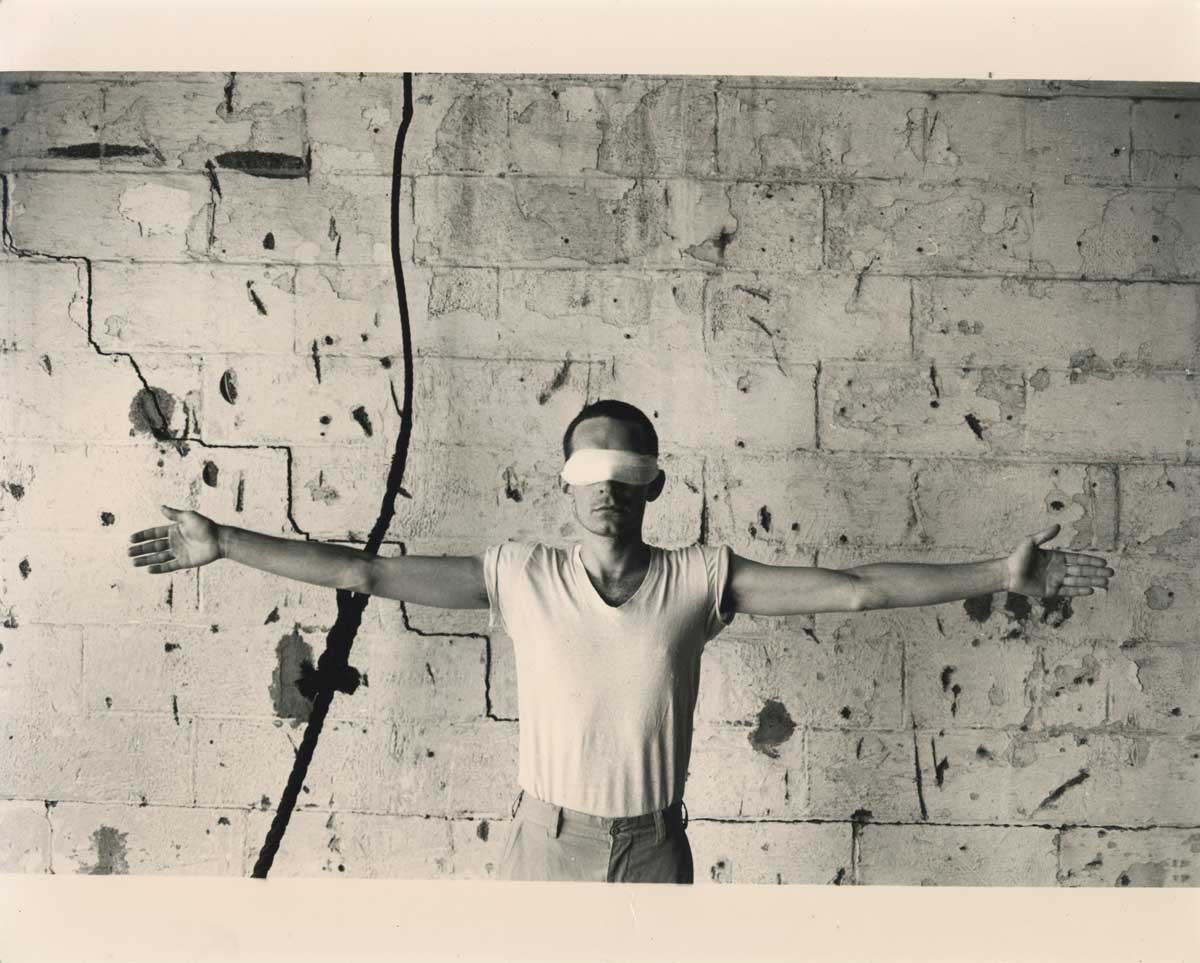

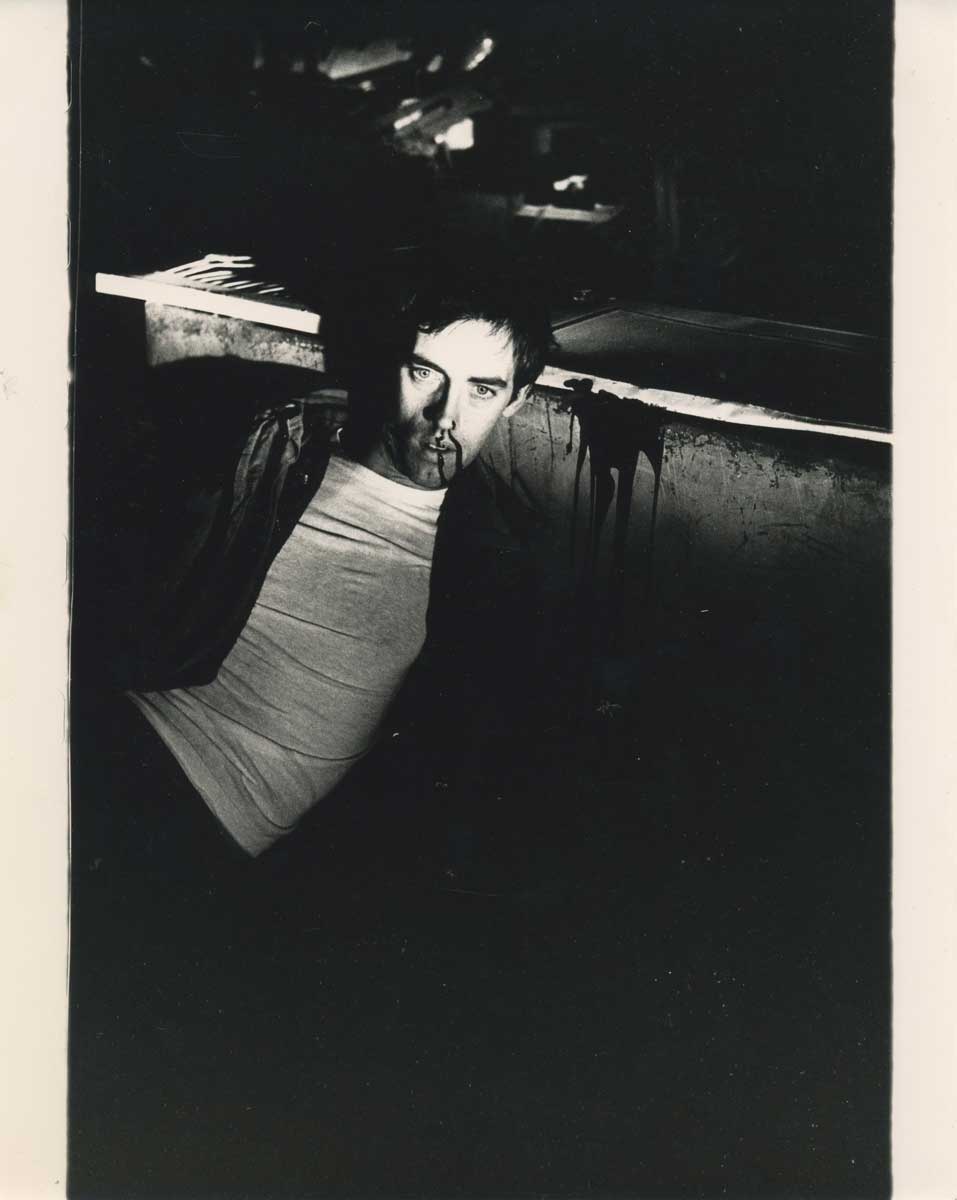

In a world so saturated with imagery, can art survive as a reflection of one’s own meaning? I believe it can, but not by cold-calling on itself. To make effective art, one needs to know their own subject matter. This, I think, is one of the greatest downfalls of contemporary art. Most artists today know more about the systems of the art world than they do about the world itself. Wojnarowicz’s little house that burns is both our prison and our world; this little house that burns is the art world itself, and if we look through the windows, all we see is the rapid oxidation of the world alight. But what lies beyond those flames is life. As I watched Wojnarowicz use his body as a vessel for life, and not as a subjective tool to view life, it seemed more than apparent that hell, as much as heaven, is a place on earth, and both should be tools of art-making. By accepting both heaven and hell, Wojnarowicz transgressed the body of the artist, moving it between the shadows of the every day and the ideas of an art form. One never sees the physical manifestation of “him getting rid of himself”; we only come across his corpse—shed like a snakeskin. The artist leaves ghostly traces roaming the sphere of the earth in the form of texts, photographs and moving images. His phantasms scratch our retinas. Abstract and disruptive, these narratives both confuse and intrigue the observer, hypnotising through the flickering images.

What’s novel about Wojnarowicz’s work is that, as a viewer, you don’t think about the word “Art” necessarily, but instead, you succumb to its energies. You’re possessed by it unknowingly, and it’s like a freakish occurrence, similar to a rainbow in both hail and sunbeams. Wojnarowicz captures the viewpoint of unsuspecting viewers and makes them stare. This emotional infrastructure cannot be so easily detached from its environment if it is to continue living. Wojnarowicz seemed to know this, and we need to realise that the art world almost immediately causes art to perish unless we care more about life than art, or that the art that is produced is stronger than the art world itself. Wojnarowicz’s work signals that we must become the apparatus that reforms itself if we hope for change.

Whilst watching Wojnarowicz’s work, I think of how we watch fires. Watching flames lick up walls, we become a viewer in limbo, both horror and peace oscillate the eyes. I think back to watching things burn—buildings, bonfires, matchboxes. I always felt it was very quiet when things burn, like the first snow on a winter’s morning. This potential for silence panics me. I don’t want to watch Wojnarowicz as a passive pair of eyes. “…things just touch me less and less” his words reverberate from another video.

“I will wake you up and tell you a story about how when I was ten years old and walking around Times Square, looking for the weight of some man to lie across me to replace the nonexistent hugs and kisses from my mom and dad, I got picked up by some guy, who took me to a remote area of the waterfront in his car and proceeded to beat me up, because he was so afraid of the impulses of heat stirring in his belly and how I would have strangled him, but my hands were too small to fit around his neck; and I will wake you up and welcome you to your bad dream.”

Looking back at Wojnarowicz’s body of work, I grasp his assertion that trauma and pain are not simple spaces, and that we’re all—with or without our consent—complicit and coerced inside them. We live in a society of trauma, we’re both the victim and the abuser. Nobody’s innocent and everything’s rhizomatic, be it in the past, present or future.

I start to understand, after hours inside Wojnarowicz’s work, that I’m stood in that burning house and that this is what keeps me here, what keeps drawing me to him. I’m as much a burning house as the joy-riding arsonists that built the foundations to let it burn. This house was burning before I was born and will continue to burn after I’m dead. We can see the house as a metaphor for us, for humanity, society and the world; for our soul and our psyche. But what if we don’t just watch the house burn? What if we pour petrol onto the house, or try to put it out?

Words by Penny Rafferty

Photography by David Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar, Ivan Dallatana, Marion Scemama, Andreas Sterzing, and Frank Sperling