“As a painter, if you paint flowers you’re boring, but if you paint orgies, you’re a provocative painter”

“How did you find me?” Aldo van den Broek asks as I enter his spacious, sun-kissed studio. Confusion strikes. I am pretty sure I am supposed to be here — in fact, I am even more sure that I am late. Surely, he was expecting me? I give him a puzzled look. “Bonne Suits, maybe?” he prompts, naming his latest fashion-art collaboration — and clarity washes over me. His presumption of anonymity is charming: having exhibited at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Ron Mandos and is now presenting at Gallery Vriend van Bavink, following several appearances during Berlin Art Week, Aldo van den Broek is clearly far more celebrated than he realises.

Known for his grandiose, multi-layered paintings, the Dutch-born artist — who now splits his time between Amsterdam and Berlin — creates between the chaotic bounds of fantasy and reality, exploring the human experience within the realms of punk, sex, architecture, animalism, and more. Daringly gifted, and unashamedly vulnerable, Glamcult checked in with van den Broek ahead of his upcoming show for Art Rotterdam last spring. We spoke about his creative drive, cross-cultural experiences and his triannual attempt at sobriety. Chasing him with a voice recorder around his studio, van den Broek showed me his latest works, discussing their conception and the scandalous tales surrounding them.

This studio is amazing. How are you today?

Thanks. I’m only here for a month, so I need to run with the unpredictability of it all. I’m just painting, playing, destroying and replacing to make it all happen. But yeah — I’m pretty good. I quit drinking a few weeks ago (and I had corona), so I’m feeling kind of weird… but, maybe in a good way? I’m starting to feel myself coming back, it was all getting too chaotic.

Health and productivity: they always tell us they’re synonymous… Right?! I just had this solo exhibition with a lot of “side events”, and now I have Art Rotterdam coming up, so I’m trying to get back into a normal schedule. You know, the whole “start at nine and finish at six o’clock, with no night-time work”? In this new studio, I decided not to put in any lightbulbs so when it gets dark, I have to go home. I’m forcing myself into a disciplined routine. Again, moving away from the chaos and trying to get a grip on life. This is a routine I take on three times a year or so. I need to be sober.

…which is harder than you think here in the city of hedonism.

I also have a new dog, so I walk with him every day for an hour to the studio. As I said, I’m not really a healthy person — I don’t aim to be a healthy person — but sometimes, it’s good to get back to a baseline… and then fuck yourself up again.

It’s all about the mindset, and it sounds like you’re killing it in that department. Jumping back to the start of your artistic journey (before the chaos), how did it all begin?

There has always been chaos. I’m a chaotic person, but I work very directly between both reality and fantasy. When I first started, I had way too many impulses; I was painting, doing graffiti, making photos, sculptures, music — literally, everything all at the same time. It was too hard to get a grip on any of it. How- ever, the moment I decided to focus on just painting was when I began working on clear projects, with a clear direction. For example, I made a whole exhibition in and about Belgrade. This was the start of me using divided, clear-cut themes in my work (mostly using countries as my point of inspiration). This influence also provides the body of work with the right context for it to be viewed in.

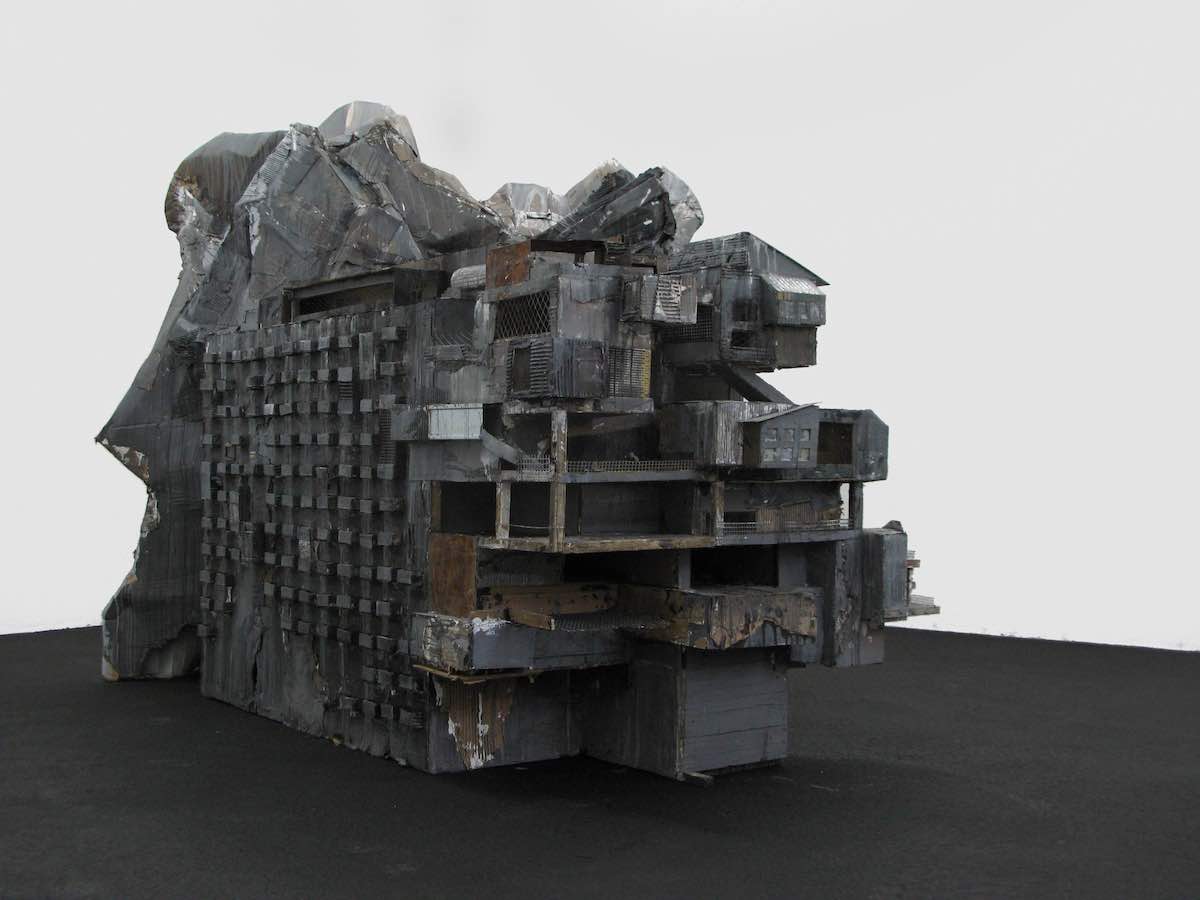

One of my all-time favourite cities. Tell us about the MADE IN BELGRADE series. The pieces are dark, dimensional and architecturally focused…

I love it there too. The project came from my fascination with both the city’s architecture and people. In the Netherlands, the last thing people want is to live in concrete highrises; however, the attitude was somewhat different in Belgrade (despite people living there based on uncontrollable circumstances). I was fascinated with not only the architecture but also the ways in which people thought about it: where to place it, at which degree the buildings should stand, how the roads are connected and so forth. Making sure it always fits. But besides this perfect planning, I realised people would always create their own walkways. The architects will put a road in the most obvious place, but the inhabitants just walked through the garage to access a new road, creating their own path. Looking on, they felt like elephant roads (because of the straight lines where people had continuously chosen to walk the shortest route). So that’s where my fascination for the MADE IN BELGRADE project began. We are all animals inside.

This immersion into a city — the culture, the people, the architecture — to create art seems to be a common practice of yours. Like the Japanese Shunga series, which documents orgy culture.

Yes — I also did the same in Georgia and Siberia, and then last year I went by horse through Mexico. When I do this, I don’t have to think about what I’m going to paint; it just happens directly. But yes, it was also the same with the Shunga series. I was fascinated by how the culture there is to never talk overtly about sex, especially between genders. They would not allow me to get into any sex-related situation, be- cause my girlfriend was with me, and that’s not allowed. They would be too ashamed because when there’s a girl present, you’re not supposed to show that you like sex. However, when there are just men together there is unlimited sexual freedom.

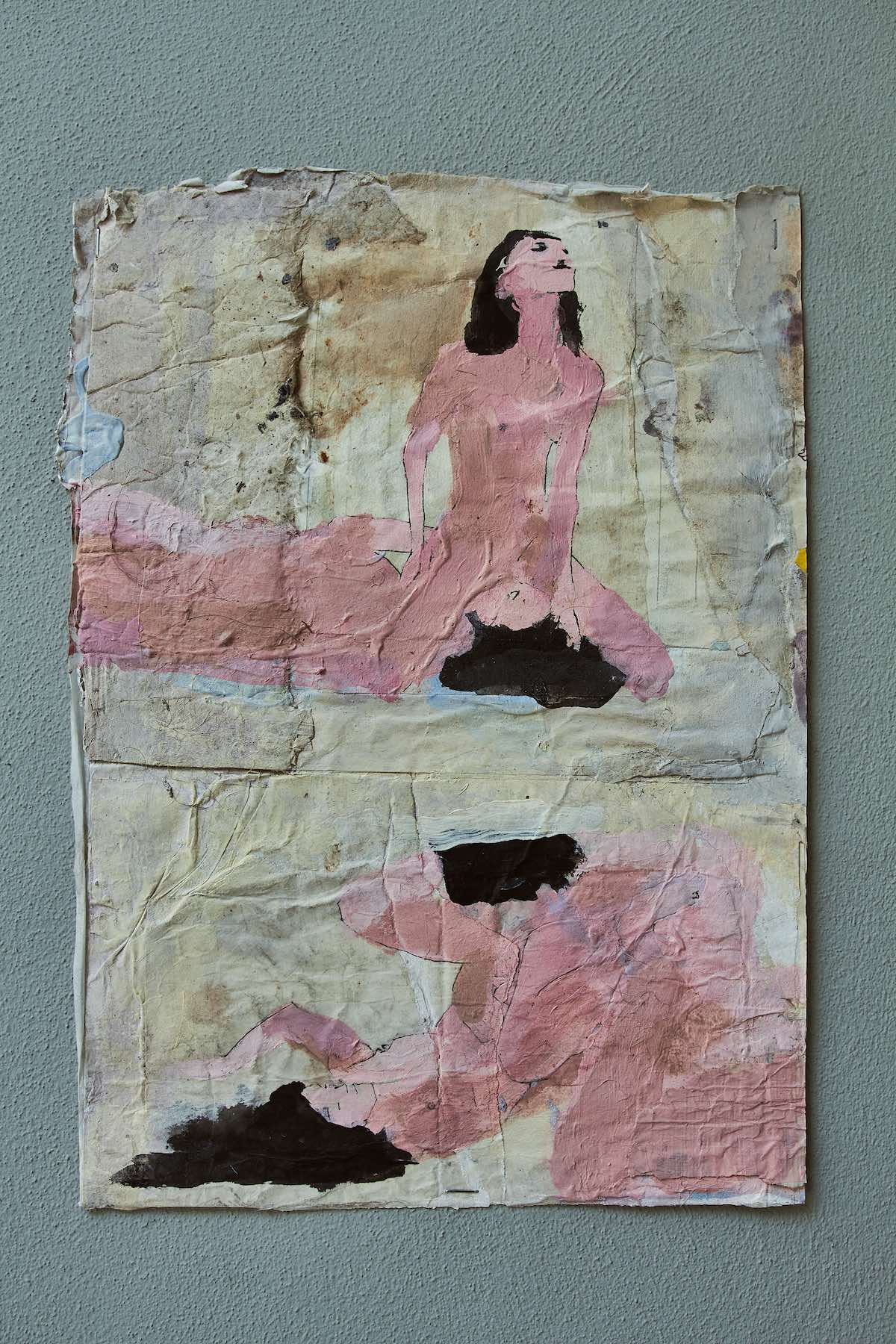

Shunga series, Work in progress, 2022

That’s fascinating. But then, why would it be the same experience as in Europe? Shunga [the Japanese tradition of erotic art] is so different to early modern European erotic art, which is elusive and, largely, modest…

In Japanese Shunga, they paint with, like, six dicks! They depict the fantasy in art, as opposed to the real… this fantasy is also visible within the linear aesthetic qualities of the tradition: leaving out shadows, for example, suggests a fantasy equal to the six dicks. This contributes to the level of freedom, where sexual themes can be discussed without necessarily being talked about openly. But totally: we have a different fantasy. For this series, I ended up using the “western fantasy”, which is more subtle, in combination with classical Shunga, making it in my own way. I also did a whole series with the blossom flower.

It’s a beautiful combination, of bodies and blossoms.

The blossom is also known as the Sakura, a tree that flowers in the spring. This combination fits for me because the cherry blossom is also representative of seeds spreading, and Shunga’s literal translation is “spring”. So, for me, Japanese spring is the blossom, which is both sexual and beautiful. As a painter, if you paint flowers, you’re boring but if you paint orgies, you’re a provocative painter.

Hence the fusion: the boring provocative painter. But this work is so different — softer than your other series. The brutalism is gone, yet the pieces are equally raw and honest.

I like the contrast. That’s how I work. But indeed, there is normally more architectural work. I’m going back to Georgia in two weeks to do a project about architecture in Tbilisi. I will be looking into these flats blocks — 20 of the same, all next to each other. They were built during the Soviet Union, so when it collapsed (and the rich and poor were still living next to each other), the rich people thought, “Okay, I’m going to make our balcony twice as big.” This made their living space bigger. Of course, the poorer guy next to it thought, “Yeah, I want that too, but I don’t have stones…” so they tried to replicate the extension using trash and wood. Consequently, these buildings have become very characteristic and therefore fascinating to me. No building is the same, no balcony is the same. It’s comparable to vertical slums; vertical frames of existence that develop over time. They call it Kamikaze Loggia because sometimes, one falls.

This is another common human reaction to forced uniformity, like the elephant roads. Identity, and modification, are inherent to our nature. It’s expressionism—whether it be an extended balcony, designer bag or tattoo. We’re all dressing up beyond our four-walled homes or our bodies’ limitations.

Exactly. It’s all about the individuals, and their individuality cohabitating in one place. And just like my paintings, it is always growing and adapting.

Can you talk us through this process of growth and adaptation?

My work has many physical layers. I extend each piece so much over time by adding and taking away parts. I do this to the point that I don’t always know what’s underneath anymore. Often, I will see a problem and have the urge to solve it. If I drink (or am drunk) I’ll make a piece bigger and then the next day I reflect and realise it still isn’t right. This leads to another correction, and so the painting becomes even bigger. I never know from the beginning where my work will end up.

How do you ever finish — or even begin?

Sometimes, aesthetically, I start with simple drawings. For example, with the Shunga series, it all began with simple lines coloured very precisely. It didn’t feel right, so I let my daughter start painting on it, and she fucked it up. She was really sad. But I explained to her that it was okay and that what she did was good; the painting needed it because, now, you don’t see a literal penetration or something like that, but you still know what’s happening. I’ve been trying to push this illusion more in the paintings so that they become abstract. In this way, if you see something dirty, then it’s your perversion. I think that’s more interesting than really seeing a penetration.

Work in progress, 2022

Work in progress, 2022

It’s like the Rorschach [inkblot] test, where you’re presented with something abstract, and a psychiatrist will ask what you see.

Yeah, exactly like that. Or like in fashion, with lingerie. The lingerie covers the “important parts”, making it more pleasing as you are left wondering what’s underneath. I realised that, with sex, this is what creates the magic. But I’m also trying to push it to the right limit. For example, in one of the Shunga pieces, you see two breasts and I was thinking this morning, “Maybe I should make them disappear?” Because it’s already clear what’s happening.

It’s like imaginative foreplay.

Yeah. And you don’t have to see if it’s a man or a woman — it’s irrelevant… But ultimately, going back to the question I never know how big the painting is going to end up, or when it’s finished, it’s totally last minute. For example, with my latest exhibition, I brought 60 paintings, but in the end, there were only 40 left to show. It’s like, kill your darlings.

Good pivot back to the question, ha-ha! And this makes perfect sense: fantasy is limitless — so inevitably, the process is too. It’s not as black and white as, say, painting a bowl of fruit or a portrait.

I do try realism sometimes, just to see if I’m able, to test if I’m a good painter or not. But I rarely show these skills in my exhibited work. But, sometimes, I will add small realist motifs into things — it’s all part of the process, and the process is the most important thing for me. I find it sad that nobody ever gets to see that part. After all, at the end of the day, I have to show a finished painting.

You could always make the process into a performance-art piece, “behind the curtain” of Aldo van den Broek.

I should! I do sometimes think about it. I do like attention, but not forced attention. I try to tell my story through layers and add-ons, but you never know if the person looking at it will get that.

But that’s also okay. It’s nice that every viewer reaches a different outcome, and has a different perspective.

Yeah. It’s okay because I know the story.

Your work spans several disciplines and contexts, from portraiture to architecture, gallery spaces to raw environments. How do you feel your aesthetic performs differently in these opposing spaces?

I think because my work is normally quite rough, there’s a contrast created in a clean gallery space, and somehow, the piece becomes bigger and the work shines more. These spaces help amplify both the work and its shape, where a raw setting will only absorb the piece into the wall. This can also be nice, but it creates references in my head that are too similar to street art, and I hate street art.

You hate street art? You used to do graffiti, no?

Graffiti is more about adrenaline, it’s more like territorial pissing. I’ve taken some elements from graffiti which you can still see in my work, also in my materials and my scaling — but not so much the skills.

A lot of the pieces in here are sort of huge. Has this always been the case? Since the graffiti — not street art — days?

I have a nice story about this, it’s not about me, it’s about my son. His school in Germany called me to tell me they thought he was autistic because he’d been playing on his own in the garden with a stick. Immediately, I thought they should be careful putting him in a box so young — he’s only three. Anyway, two months later they called me again and asked me to come to the school. This time I went in, and they took me up to the fourth floor so I could get a view of the garden from above. The teacher said, “Look outside,” and there I saw that with that stick my son had drawn a big guy with a dog with a small boy next to him…it was me, my dog and himself scaled at 20 metres. You see, my son was so used to my studio, where everything is oversized. For him, playing, painting or drawing on the ground in this way was normal (I also paint everything on the ground).

That’s amazing! What an eye-opening experience of how children learn, replicate and recreate.

Yeah, so even though I left graffiti behind, it still plays a role. I’m also 36… I can’t lie down in the bushes and wait until the police are gone anymore. This is just a different phase in my life, I don’t like street art. It’s also a teenage thing, you know? It fits when you’re rebellious and you don’t want to be loved. Rather, you want to be fighting all the time.

We spoke about the process of creating art in different places around the world. But we should also mention how the materials you use are also taken from those places, acting as a kind of love letter to the land.

Most of the time, if I’m somewhere abroad for a project, I rarely paint whilst I’m there. This is because I want to see and experience the environment first. I try to integrate myself into the community, and most of the time, the poorer community. I live there and get into a routine. I’m a part of it. Meanwhile, I collect stuff which I see on the streets (or that people give me) and then I send it to wherever my studio is at that moment. Now it’s Amsterdam, but I lived in Berlin for ten years before. I also lived in a castle for three years. I think this process of collecting and sending is really important because I don’t work with photos or anything. It’s all in my brain, like a sponge. It also becomes about how I remember it, not what is necessarily existing. For example, in Russia or bordering Russia, there’s a lot of alcohol… so remembering these places, it’s even wavier. It’s a very twisted connection still in your head, but that’s also what makes it art. Otherwise, you bring back photos and paint the photos, and that’s just reproduction, there’s no identity in it. I find this way of creating art elevating.

For sure. A lot of your work is incredibly voyeuristic. Creating a sneak peek into someone or something you maybe shouldn’t be seeing. Is this intentional?

Yes. Do you see all these cigarette packages? [points to the ground] I smoke a lot, and I wanted to get my tax back from it (it didn’t work out). But I have a whole stack of around 50 right now that I take with me on the train to Berlin. I prepare around 20 packages and then draw the faces I see on the train on them. When I come back to Amsterdam, I then begin to work them out. They never look like the person, but that’s also irrelevant. I look at the shapes and light fall, I need this sense of voyeurism because otherwise, all the people will look like me… which would be so boring. I don’t have the photo afterwards. I have nothing. I only have a few lines which I drew myself.

Shunga series, Work in progress, 2022

Is it the same process as the in your Face series?

So, these came from when I lived in a mental hospital for four months as an artist in New York. It was the only free mental hospital in New York, in Brooklyn. In 2015, I observed the patients in comparison to what is considered “normal”. I sent it by post and it disappeared. Suddenly, four months ago, my parents told me that an envelope had arrived with sketches from New York in it. So, these pieces were in the air for, like, seven years. I picked them up and now I don’t know what they look like, so I’m now trying to find the right balance.

Within this balancing process, do you feel as though you give these faces a personality? One that you create for them?

The personality is always mine. It’s always kind of cheesy to say, but it’s always a self-portrait — because it’s a reflection of my mood. I paint on them when I’m happy, when I’m sad and when I’m angry. I also allow music to influence this… altogether it creates an effect.

You, yourself — and the music you listen to — are therefore penetrating the work, not necessarily intentionally?

Sort of, but if I put on some dark classical music, then everything becomes dark.

And do you ever look back on pieces that you’ve created in one mood — for example, dark — and regret the energy you put into it? I know I often feel guilty for the work I’ve put out in vulnerable moments, whether it’s good or not.

Totally. Me too. Except, I have to say, I do take advantage of my sad periods. Like, you shouldn’t make a portrait when you’re happy. Maybe just paint architectural work instead, to try and maintain happiness. You mustn’t try to sink yourself into sadness just to create art. You need to find the right balance. There’s no trick. Depends on how much you want to control it as well.

I’m a control freak.

I try to think of it as organically existing.

PALIMPSEST TBILISI, 2022

Work in progress, 2022

Photography by Jaane

Notifications