“Pop is political by definition — it belongs to the people”

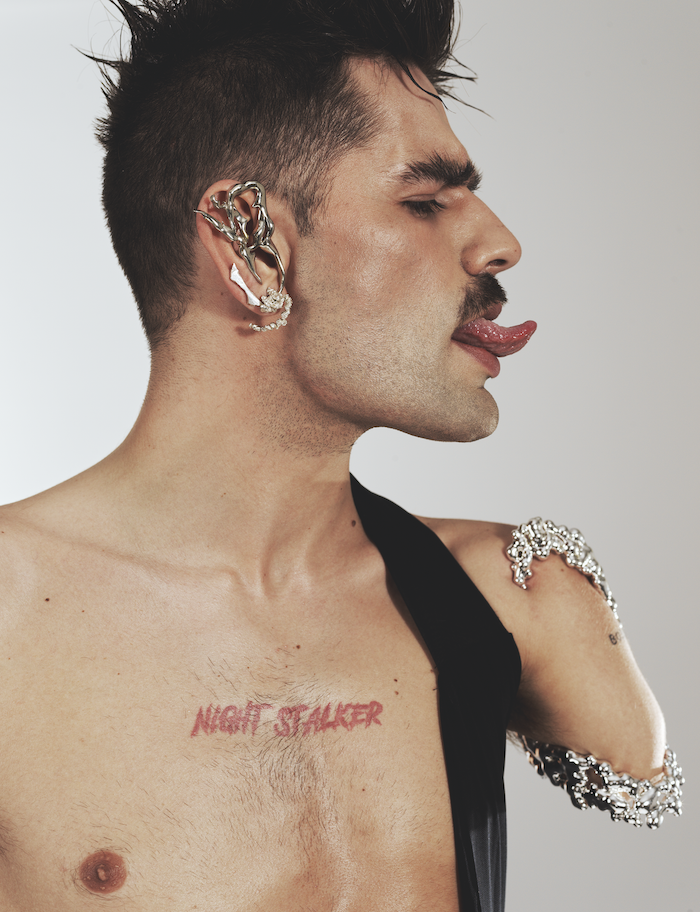

Dress LARUICCI, arm jewellery ARMOR, ear cuff AMORPHOKYRIA, earring COLOMBE D’HUMIÈRES

Love is at the epicenter of all creation for Lucky Love, a.k.a. Luc Bruyère— a poetry-ridden mischief-stirrer ready to wipe out everything we were told about manhood, Queer intimacy, and kinship. What is left following his blazing trail is a world transformed—with his music being a sanctuary for anyone who feels excluded by the dysfunctions of a rotten system. His ethereal, aching vocals are both liberated and liberating, encompassing the romantic grandeur of olden poets and the bold cheek of a modern pop star. The true fuel upon which his star burns so bright, though, is his luminous ability to transform pain into grace, reminding us of the resilience of the human condition. In light of the release of his first album, Tendresse, we felt compelled to learn more about the artist’s unstoppable vision.

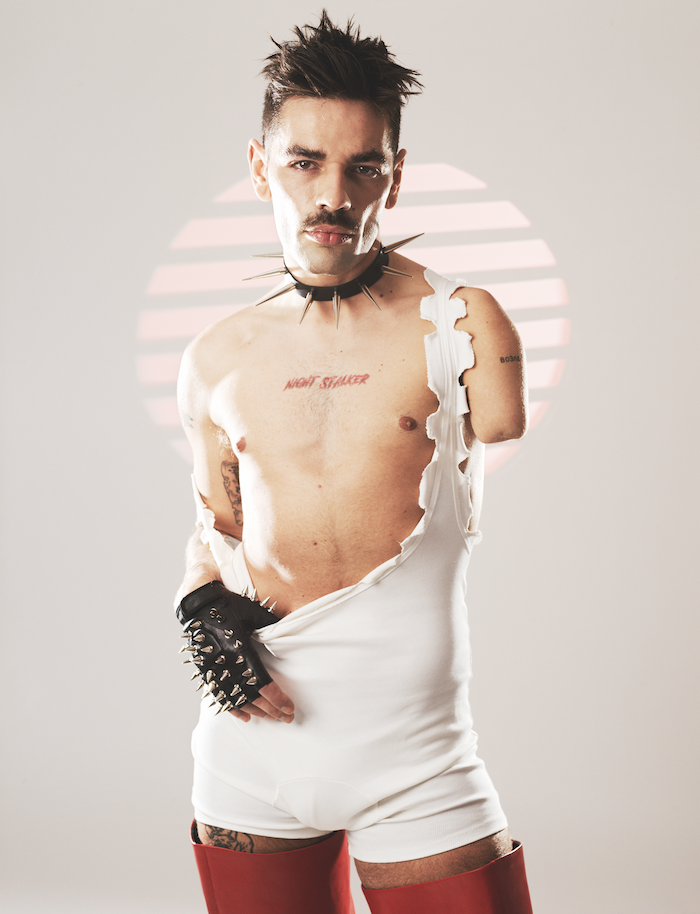

Bodysuit DE PINO, boots UNTITLAB, glove and choker MALDITO

Hey! Great to speak to you. How are you doing today?

Today I’m happy! It’s very sunny and beautiful outside, and I’m really excited— I just found out I’m doing my next show at Soho House in Paris later this month.

How exciting. Congrats! You started your career as a dancer, then as a model, actor and screenwriter, among many other things. How did you land where you are today?

My dance education was the first thing ever to come into my life—I started dancing when I was five, and it was the only thing I wanted to do as a kid. When I was about fifteen, all the trouble began. I loved dancing, but it wasn’t enough to express myself—I missed words; I missed language. I was then scouted for Blue Is the Warmest Colour. I had a small role in it, but the director was impressed and brought me to this theatre school in Paris, where I began studying acting. One night, I went to a cabaret place called Madame Arthur. The art director of the cabaret came up to me and asked, “Do you sing?”. I said “Yeah, but only in my shower.” Two days later, I was hired by the cabaret and became a transvestite actor called La Venus des Mille Hommes —which translates to The Venus of a Thousand Men.

What a beautiful name!

It’s a tradition—when you come to Madame Arthur, you need to find your own name and build a character around it. A lot of people told me I remind them of the statue La Venus de Milo, so my character was born from the wordplay.

Bodysuit DE PINO, glove and choker MALDITO

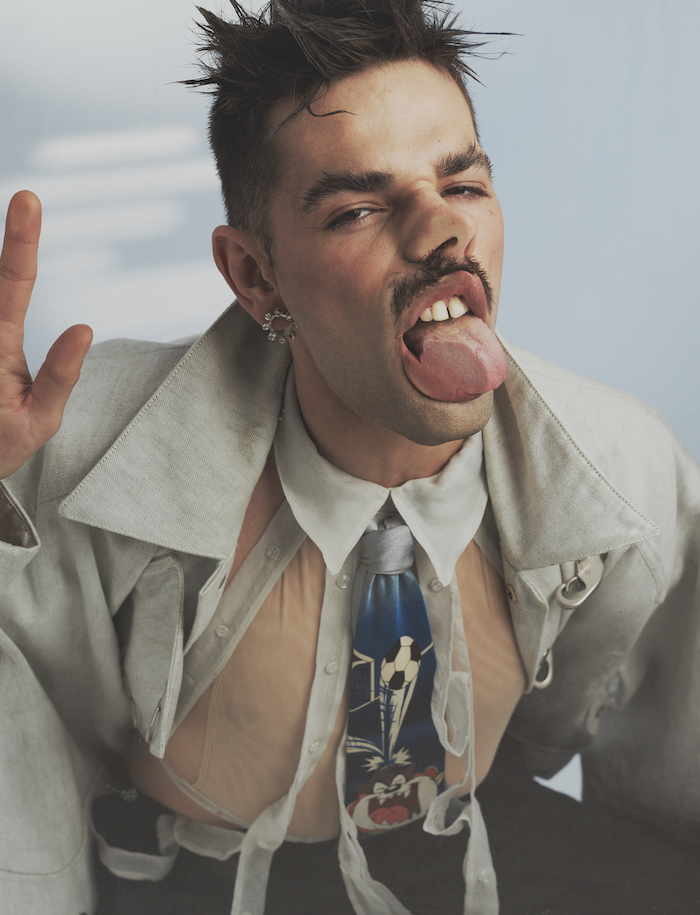

Coat ÉTUDES, shirt TRIBAL HOTEL, trousers PROTOTYPE, tie stylist’s own, earring COLOMBE D’HUMIÈRES

I’m so curious about your work in drag cabaret. I’ve read that Madame Arthur was one of the first of its kind in Paris. What was it like to perform there?

It actually started as a refuge for trans women who were working on the streets. According to legend, one night, a famous trans girl from the 50s was beaten up on the street. She came in covered in blood and bruises, but then she saw a piano and just started playing a show. That’s how Madame Arthur was born. I felt incredibly lucky to be a part of that place, and it was a huge responsibility to preserve this unapologetic way to perform a show. You don’t go to Cabaret to just be entertained. It’s also where you ask questions about yourself, acceptance, society, and your role in it—it’s a really political place. Of course, there’s fun, and I found a unique freedom of being able to give people a show but to also make them think about the wrong and the beautiful aspects of our world. It was a special time—I was super young, gay and free. I loved working at night— I loved the poetry I found in the nighttime. It was also the first time I felt like I belonged to a community, I had a chosen family. This experience has built a lot of who I am now. And, it was at Madame Arthur that a girl came up to me and asked if I wanted to make music independently, which is how it all started.

Your artistry today continues to radiate this freedom of being both visually and sonically stunning as well as politically impactful. How did you find your place within music?

The real question about my career was to find the legitimacy to do what I do. I never studied singing formally—it’s something I learned on stage directly, so it was hard for me to recognise myself as a singer. With dancing and acting, you become a tool for delivering someone else’s speech, and I loved this position of humility. But at one point, I wanted to share my own ideas. With music, there are no filters between your audience and yourself.

Often, learning how to translate someone else’s ideas also helps you refine your own.

True. The moment I stepped into a music studio, all my previous interests made sense—they prepared me for that moment. I use my acting in music videos, dancing in performances and so on—music is a complete form of art to me. Building my first album was very much like therapy. I needed to settle down and look behind me. I believe when you sing, you must have an urge to sing, an urge of delivering something to people. Fashion has played a part, too—I’ve been a model since I was sixteen. Not that you have to lie, but you have to be yourself less. With music, if I’m not entirely honest, it won’t work.

Top and jeans CONSTANCE TABOURGA & THOMAS SANTON

I love the transparency co-existing with ferocity in your work. Like in Masculinity, you’re not afraid to both open up about your own identity and to ask, “Who gives you the right to run the rules?” in response to forced patriarchal notions of what masculinity should be. Could you shine some light on how you approach songwriting/music-making?

I don’t have one process, it always depends on the song. For Masculinity, I was at home, and it was like 1 a.m… My good friend was on the train to Ukraine and created this little melody. He sent it to me, saying that it reminded him of me. I was fully naked when I heard it. I looked in the mirror, got a microphone, and the first thing that came out was the line “What about my masculinity?”. I think it’s the most vulnerable song of the entire project. I’d never felt safe to say that it’s hard to be a man. This patriarchal system is not only detrimental to women— it destroys everyone who doesn’t adhere to the idea. And I am one of them. I grew up without an arm, I was gay, I found out I’m HIV positive. This image of a strong “alpha male” is so far away from me. Even in the gay community, there is this fixation on hypermasculinity. I was twenty-seven when I wrote Masculinity, and it was the age when I thought I’d become that strong guy they all talk about. I quickly realised that it didn’t make me happy at all.

It’s such a shame that we are forced to shrink and contort ourselves to fit these two-dimensional standards of ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’. There is so much strength and nuance in both—it’s about expanding our perception of their definitions and nurturing the parts that resonate with us.

Exactly. My aim was to find different shapes of masculinity instead of having one example of it. That’s why I sing “Do I look like a boy?”. Who decided what a boy is?! I don’t want future generations to think that’s the norm. Writing it, I was thinking of young me, a fourteen-year-old Luc who comes home from school after being bullied the whole day and needs this safe space. I wanted this song to be a refuge for anyone who feels like they don’t belong. Masculinity started off as being very personal, but I soon realised that it had a very big political aspect that needed to be explored. We’re in 2023 and we need to reinvent the world because obviously, it’s not working! There are so many of us speaking up now. Also, as a model and a singer, you always have to be this seductive persona who is on top of things. You have this industry behind you that tells you that you are a product and have to fit into that box. Masculinity was a big ‘fuck you’ to anything that people were expecting from me. This was me writing my own rules.

It’s interesting how the most personal is often the most political. This ties in with your other works as well—Love, Masculinity, Paradise… All of your singles are like standalone testaments to what is important to you. Has this been a conscious process?

In the beginning, I was just writing songs, and then I understood that all of them were a step I took in my life. Paradise was telling the world that holy beauty is in humanity—a reminder to stop looking somewhere else, we are the divine thing. Love was about the values important to me. Growing up, I thought I would have to be ashamed of my love and sexuality and live it in the dark. All the references I had to Queerness were happening in the night—it was always related to AIDS because that was the reality in the 90s. Sexuality between men has always been presented as something dark and violent. But this is not my sexuality. I wanted to show young people that they don’t have to hide—you can kiss your partner anywhere because it’s love and it’s beautiful. So yeah, all my songs are always questions I’ve asked myself one day.

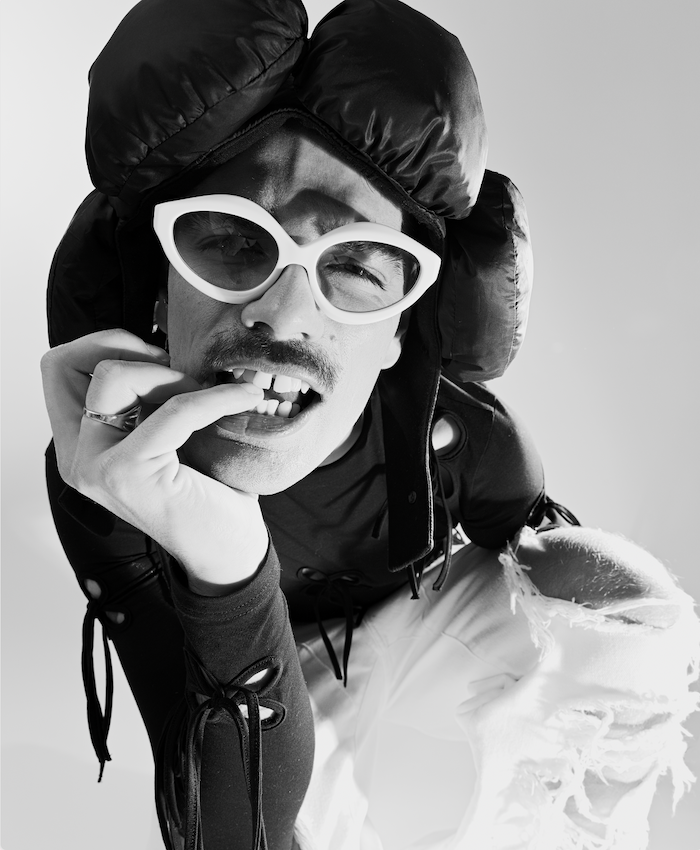

Top and hat JKIM, trousers ETUDES, sunglasses AMAURY PARIS, earring COLOMBE D’HUMIÈRES, ring model’s own

Top and hat JKIM, trousers ETUDES, sunglasses AMAURY PARIS, earring COLOMBE D’HUMIÈRES, ring model’s own

This approach builds for a very moving body of work. For your upcoming album, is there a leitmotif you’re working around, or any particular inspirations?

I’ve always been inspired by pop icons like Madonna, Lady Gaga, and Bowie—all these people who have transformed themselves to be hyperboles of a theme in society. Pop is political by definition—it belongs to the people. I love this idea of building an entire character, which is why I’m using Lucky Love as my name. Lucky comes from the fact that I think I’ve genuinely been very lucky. I knew what love was from the very beginning of my life. And this is basically the album—I’ve been very lucky to find love. I think love is what makes us human. Also, growing up in France, I’ve always had this romantic image of poetry, forbidden love, Moulin Rouge… I’ve been a fan of Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe since I was fourteen. I’ve always dreamt of this big love and feeling like I’m not alone here anymore. That’s what I want for my audience—I want them to feel like they belong and that they’re not alone. This is the thread that runs through.

With fashion being such an instrumental part of your vision, I love that you mention the exaggeration and spectacle seen in pop culture. You’re so right, it’s never a simple provocation—there is always social commentary through a personal revelation of alter egos.

I love changing my look. When I began modelling, I understood that what we call fashion is the best costume ever—it makes you play the role of yourself. By putting clothes on yourself, you can define the reason why people look at you. As a child, I was tired of having these eyes on me, to be looked at as a victim. I wanted to be powerful, and that’s what fashion brought into my life. I think I was fifteen, and I wore these really tiny shorts with a punky outfit. It was the first time in my life that I walked on the street and people looked at me for a reason other than my missing arm. This is also what I wanted with music and what Lucky Love is about—a character that connects with an audience that goes through the same shit as I do.

You also talked about the romantic side of French culture that is at the root of your expression. I wonder how this is reflected in the language of your work— you tend to oscillate between English and French throughout your discography, but mostly stick to English. What drew you to French for Tendresse?

I’ve always worked between French and English. By singing in English, I allow my work to be universal and heard by as many people as possible. Music also has to be efficient—it’s about bringing a strong idea, but you only have two minutes to do it. It’s possible in English, but in French, we need a lot of words. For Tendresse, I decided to go for French because the concepts I talk about are strongly related to my French side. I see Tendresse as a value much more in French than in English. I think it all relates to the way we touch each other, the way we hug, the way we kiss. It’s all this beauty about France—at least how I see it. The other day, I asked a friend of mine who comes from Russia, what place love held in his education. In France, as soon as you go to school, love is the first thing. In America, there is this American Dream around capitalism. Here, what we learn to be the biggest accomplishment in life is love.

It’s interesting you say that because I studied a lot of French literature at school, from a very romantic angle as well. Where I’m from, Belarus, it seemed like such an unattainable, borderline stereotypical perception of love. It almost felt too poetic to be true.

For me it is true. I’ve travelled a lot, but I’ve never had this feeling outside of France. I had this concert at L’Olympia, which is the most beautiful venue in Paris. It was meant to be this big milestone that I was supposed to feel proud of after. The show was amazing, and my audience loved it. But when I came back to my little empty room, the only thing I wanted was for someone to be waiting for me backstage to share this happiness. When I’m in love, I’m alive. I think it’s very French of me—which is why Tendresse is in French. Also, there is just so much more love vocabulary.

Jumper 8IGB, underwear LARUICCI, shoes UNTITLAB, earring D’HEYGERE

The English language was definitely not made to express deep, emotional feelings!

I am married to an Australian, and having a fight in English when you’re in love is not easy! It’s so hard to express your feelings and their nuances. If only he could speak French, we wouldn’t even fight at all, haha.

Let’s talk about performing live. With such passion for theatre and performing arts in general, what does being on stage mean to you?

I think music becomes real only when you’re on stage. The people you only see as Spotify analytics actually become human. And I receive so much love from my audience. I remember this woman at a show, she was around forty-five. She said she came because after listening to Masculinity, she found that her expectations of men were wrong. She told me she’s been very unlucky with love her entire life, and that my song unlocked something that made her realise she was looking for the wrong things. It’s a bit sad, but I think I’m most alive when I’m on stage. Performing is like a drug. Nothing can stop me when I’m on stage. I am so strong – much stronger than I am in real life.

Performing also comes from real life. I think you’re giving yourself too little credit.

Ha-ha, thank you. I am a human, I have insecurities like everyone else —especially in our generation. We’re now placed in front of all those questions our parents were not asking themselves at all. They gave us this “gift”—to deal with the world that they left us. At least in our time, we’re allowed to be vulnerable. I can be Lucky Love on stage, but in reality, I’m just this little guy who wants to be loved.

I suppose one gives rise to the other—just like vulnerability gives rise to power… Speaking of which, can you tell me about the documentary Lucky? Its staggering honesty and resilience are extremely commendable and inspiring to so many. What was the experience of filming such a strong, personal piece like?

It was scary, I can’t lie. It began with these two directors reaching out to me saying “We think you’re a flower that is about to blossom, and we want to be there with a camera when it happens”. We had no expectations at all—we began filming like two days after I responded. We ended up shooting for over two years. It was weird to have to be myself in front of a camera. A lot of it was about trust—these people had my life in their hands. And I knew I had to give it all. People may think that I’m this rock-and-roll super funny and confident guy, so it was important for me to show that it was just what we’re selling to you. The truth is that I’ve been through all this shit, and the beauty of my life if there is one, is that I found the ability to transform it into something magical. We all have the power to do that. Your life is what you allow yourself to do with it. Making a movie out of it also helped me make sense of all these bad experiences—it didn’t happen for nothing. It happened so that I can tell my story and help people with it.

We’ve talked a lot about the past. What is the vision for the future?

I think for the first time in my life my vision for the future is to value the present. When you live in the present, soon enough it becomes a memory. The only goal I have right now is to build as many beautiful memories as I can.

Dress RUOHAN, earrcuff AMORPHOKYRIA

Words by Evita Shrestha

Photography by Enzo Orlando

Styling by Pierre Demones

Hair by Salomé Narolles

Make-up by Stella Ceriani

Photography assistance by Karim Allain

Styling assistance by Coppelia Amandin

Special thanks Réda Ait Chégou