“Funny and uplifting and a bit sinister too”

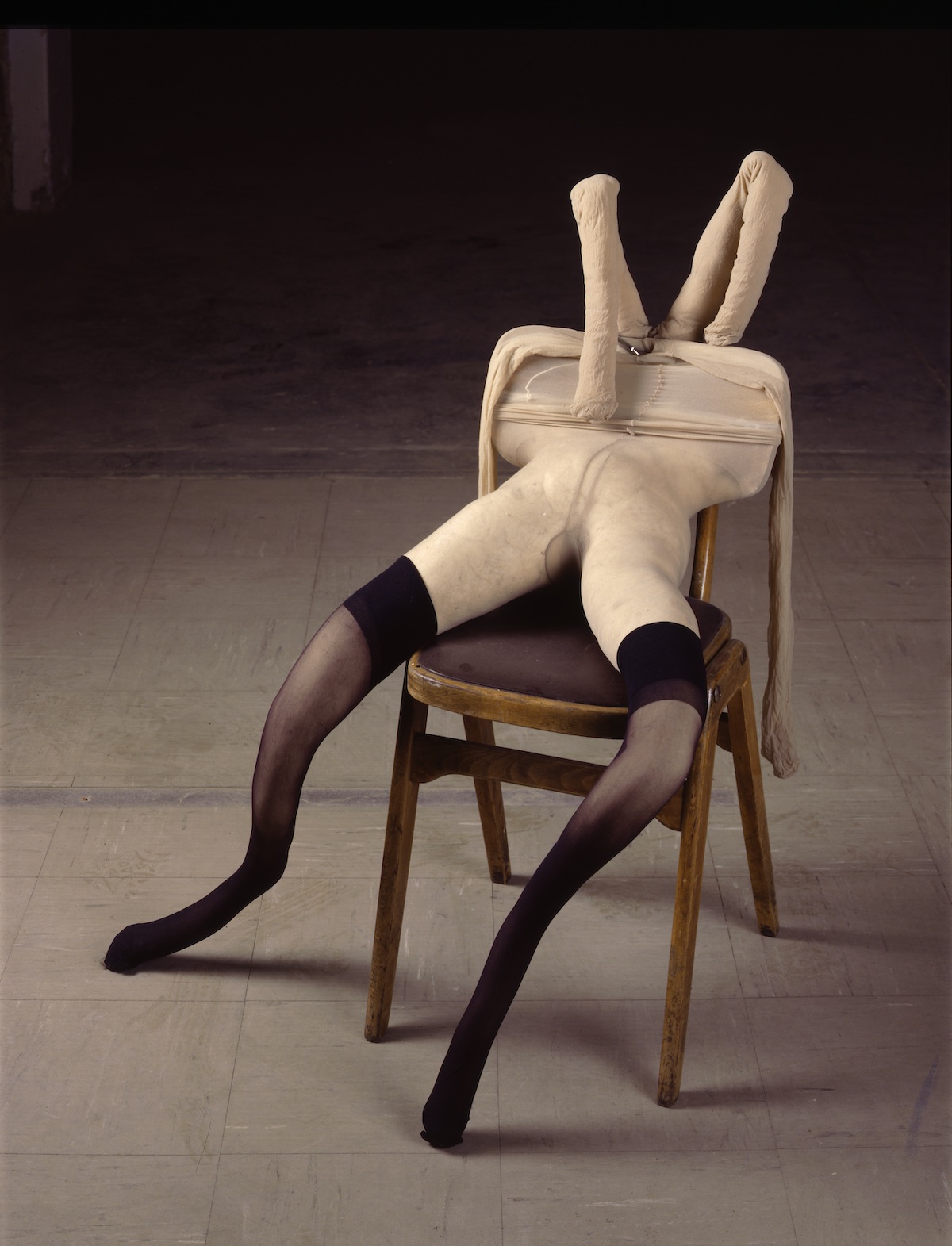

Sarah Lucas Bunny, 1997. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

Cigarettes, kebabs, yellow-stained tights and fried eggs, SARAH LUCAS has embodied punk-feminism in the British art world since her early days at GOLDSMITHS COLLEGE. After graduating in 1987, Lucas rapidly gained recognition by exhibiting her work at the iconic Freeze (1988) and Sensation (1997) exhibitions, which later played a pivotal role in the fiery conception of the ‘YBAs’, YOUNG BRITISH ARTISTs movement. Think: Surrealist Blunt Rotation. As DAMIEN HIRST, TRACEY EMIN, MAT COLLISHAW, MICHAEL LANDY, JENNY SAVILLE and Lucas enter the hazy, highly controversial, (yet media-savvy) artist arena of the late 80s and 90s. So when Lucas was later labelled by The Guardian as “the most unconventional of the Young British Artists,” we knew her upcoming exhibition, Happy Gas at TATE MODERN in LONDON, was set to offer an equally unconventional, humorous, and daring experience compared to the infamous works of her contemporaries. Rather than presenting sharks in formaldehyde (Damien Hirst) and alcohol-soaked depression-set beds (Tracey Emin) like her peers, Lucas introduces to the prestigious halls a four-decade-long retrospective of works, from breakthrough early sculptures and photographs to brand new pieces, shown for the very first time.

For Lucas, art was never a career, just “an adventure”, she tells The Art Newspaper when reflecting on her formative years. It is with this unnerving spontaneity, driven by a confessed indifference to other artists and cultural ‘heroes,’ Lucas instead places her faith in life’s hidden wellsprings of inspiration, something she discovered in the world of literature, being somewhat of a ‘bookish’ personality herself. She acknowledges the significant influence of ANDREA DWORKIN, the American radical anti-sex and anti-porn feminist writer and activist known for her critique of pornography, on her early artistic work. In her art, Lucas echoes Dworkin’s perspective, suggesting that the concept of ‘women’ is not inherently constructed but rather moulded by society, often leading to a loss of their humanity in the process. Dworkin highlights how women are often reduced to symbols, such as mothers of the earth or “slut[s] of the universe”, without the freedom to be themselves. The spirit of rebellion, which questions such symbolism and sheds light on those associated with the patriarchy, is unmistakably evident in one of Lucas’ most influential works displayed at the TATE, Pauline Bunny (1997), which is part of her informally titled Bunnies series.

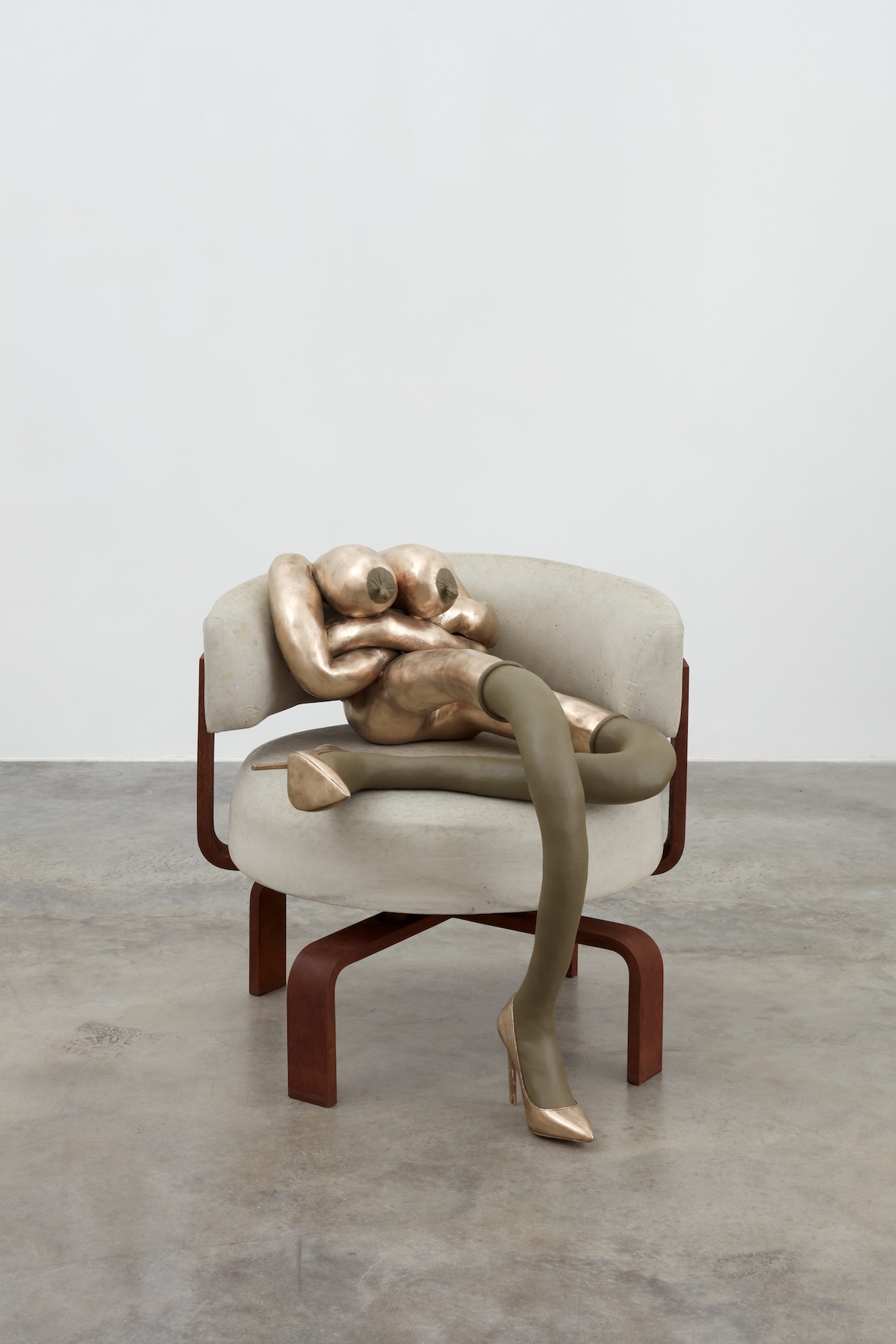

Sarah Lucas CROSS DORIS, 2019. Private collection. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

Sarah Lucas COOL CHICK BABY, 2020. Collection of Alexander V. Petalas. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

Pauline Bunny was initially a part of an installation and exhibition called Bunny Gets Snookered; where eight legs/mannequins are strategically placed on and around a snooker table at SADIE COLES HQ in London (1997). This piece, taken from the original exhibition, shows a pair of stuffed tights with cotton padding to create what Lucas refers to as a “bunny girl” form: something she views as limp, passive abjections of femininity. Within this series, Pauline Bunny is the artist’s not-so-shining star, dressed in black stockings (matching the highest-valued snooker ball), representing the pinnacle of seduction. This peak, however, is accompanied by limited power, as ‘she’—referring to Pauline—sits loosely attached to an office chair. This evokes memories of the secretary’s submissive portrayal commonly found in pornography, and it’s a theme often imitated by emerging artists with contrasting intentions, such as ANNA UDDENBERG. This disempowerment stemming from sexualisation, or as Dworkin articulates, being labelled the “slut of the universe,” brings to mind the concept of entrapment. It’s a feeling of being confined within the constraints of femininity and subservience. This parallel can be observed in the game of snooker, where, as a spokesperson for the TATE explains, “this bunny girl is only to be knocked against her fellow bunnies in a game of masculine skill.”

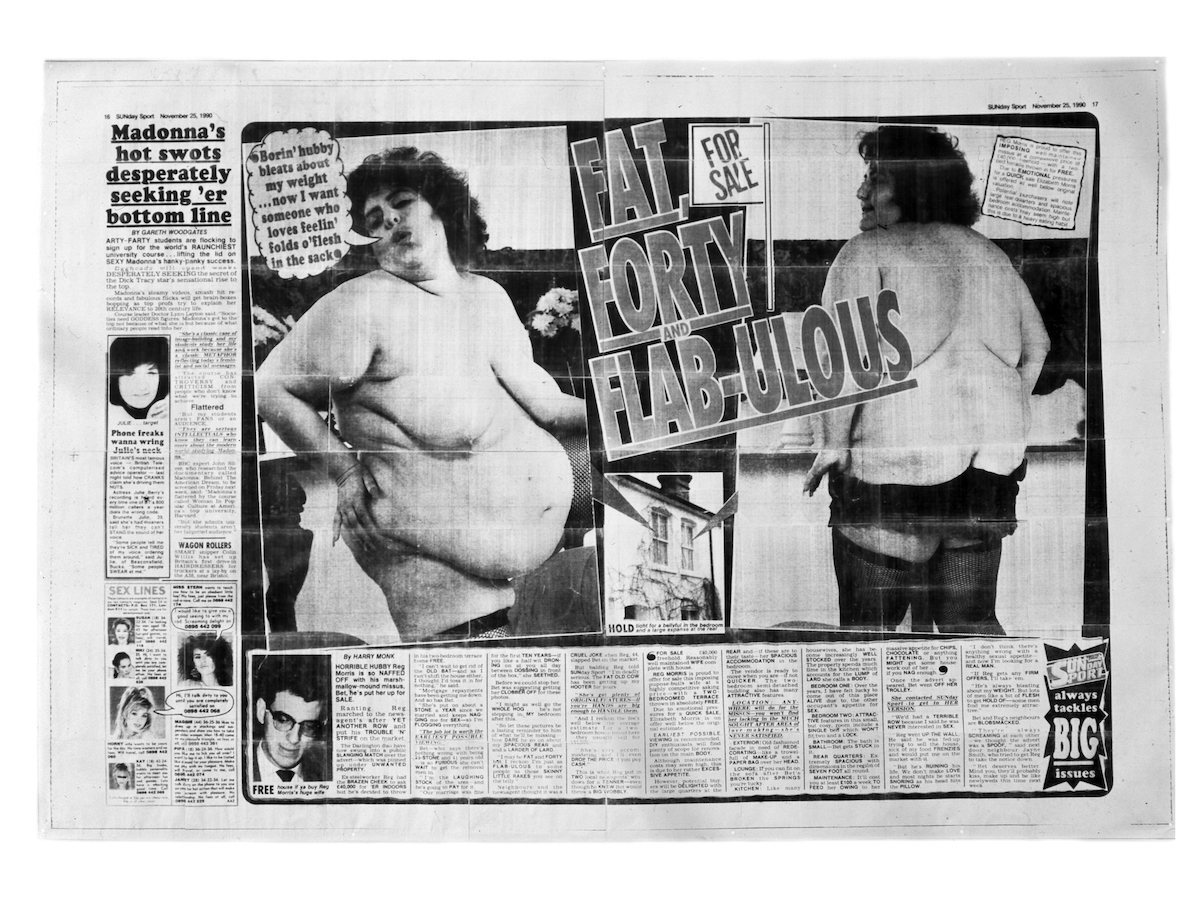

Lucas’ focused effort to challenge gender stereotypes extends beyond works like Pauline Bunny. Instead, it marks just the beginning. This retrospective exhibition, featuring 75 works, provides a comprehensive view of Lucas’ commitment to exploring themes like the human body, mortality, and uniquely British experiences of sex, class, and gender, all conveyed in her distinctive and unapologetic voice. In addition to this retrospective, the exhibition includes 16 new works, unveiled for the first time, which also highlight her evolving ideology. Among them are 12 new editions of Bunnies to the series. Lucas reflects on these updates, saying, “I’ve been making bunnies for a long while… I’m not constantly making them, but it’s something I’ve returned to from time to time, and they’ve evolved over the years.” These ‘new’ Bunnies signify a transformation within the wider cultural ideology. For instance, Fat Doris (2023) serves as a symbolic contrast to the slender allure once seen with Pauline. As the name suggests, Fat Doris has a more “voluptuous body” with additional rolls of stuffed tights. Lucas explains, “I had a sudden urge to make some fleshy ones… It turns out, surprisingly you may think, that a saggy tit is very expressive.” Beyond just a saggy breast, Doris represents a cultural shift away from the obsession with thinness that prevailed in the 90s, embodying a voluptuous antithesis in which the fleeting ‘preferences’ of objectification in contrast with its long-lasting impact become nothing short of absurd. In this context, Lucas employs macho language as a means to critique the male perspective, much like she did with Pauline, albeit adapting the language to the changing times.

Sarah Lucas Fat, Forty and Flab-ulous 1990. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Gift of the D.Daskalopoulos Collection donated jointly to the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2022. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

Two additional new works featured are two large-scale giant concrete marrows, installed outside the entrance of the Tate. Described by the gallery as two of Lucas’ “most ostentatious works to date”, these surrealist oversized forms of the original Florien and Kevin (2013), are reflective of both Lucas’ love of concrete and fascination with phallic-shaped objects. The marrow, for Lucas, signifies growth, fecundity and her typically British memories of county fair vegetable competitions. She explains these fairs, “It is a tradition in England, mostly among men, of growing super large vegetables and showing them off at harvest time”, and perhaps most significantly, she remarks “There is a prize for the biggest”. In this context, the new and improved Florien and Kevin stand out as the largest and most humorous, ‘fuck you’ response to any man who attends Lucas’ local country fair.

Concrete isn’t confined to just the marrows in the exhibition; many of Lucas’ works rest on concrete breeze blocks, a sharp contrast to the pristine plinths elsewhere in the Tate. Her choice of this basic, practical material, with an intentionally unfinished quality, underscores her well-known spontaneity. Lucas is renowned for creating many of her pieces on-site, using whatever materials are available. In her words, “What I look for in materials is readiness. Something I can get on with in a spontaneous way and just do it myself.” This ‘readiness’ carries a punk attitude, as she expands her creative horizons to include unconventional materials like “tights or cigarettes or an onion,” which aren’t typically associated with art. For Lucas, the key is the ability to act on her artistic impulse immediately.

Moreover, there is a tenderness in her choice of typically undesirable materials, akin to selecting the least preferred item or picking a slightly bruised apple at the supermarket. She elaborates, “We all might find ourselves subject to a whole gamut of emotions. The stuff of tragedy and comedy. Of daily grind and boredom. Of living. And I do find myself subject to these things like everybody else, and often I feel a tremendous urge to do something with that feeling right away with whatever is at hand, even if, at first glance, it seems unpromising.” She further adds, “There always is something. And that’s gratifying and often amusing. To express the anxiety or the anger or the joy with an onion.”

Sarah Lucas Red Sky Dah 2018. Kurimanzutto, Mexico City / New York. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London

Sarah Lucas SUGAR, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London © Sarah Lucas

As the exhibition draws to a close with the contemplation of a vice that might lead to our undoing, the last room of Happy Gas pays homage to one of the ultimate markers of the night: the cigarette. Cigarettes have played a central role in Sarah Lucas’ art, tracing back to her 1997 exhibition, The Law. Over the years, she has explored this theme through various series of cigarette-adorned objects. In the exhibition’s final room, the importance of this theme is exemplified through many different pieces, one being This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven (2018), where a Jaguar car, literally smothered in cigarettes, is unsettlingly split in two, serving as a striking symbol of destruction. In this context, destruction takes on multiple dimensions: internal, external, and physical. Lucas elaborates, “When I first started using cigarettes in art it was because I was wondering why people are self-destructive. But it’s often destructive things that make us feel most alive.” Accompanying This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven, the final room of the exhibition unveils Lucas’ more vulnerable side, featuring her Red Sky series of self-portraits, also from 2018. This time, the vulnerability etched across Lucas’s face in the portraiture contrasts with the extravagance of having these self-portraits transformed into wallpaper covering the room’s walls. The wallpaper exhibits her amid an ethereal, yet foreboding cloud of smoke, which presents far more daunting than the more comical use of cigarettes in her Muses series, in which she places the phallic-shaped habit in the orifices of body casts seen throughout the exhibition of her friends. Ultimately, however, it is the very name of the exhibition which becomes the biggest ode to Lucas’ fascination with self-destruction, Happy Gas. Describing the title as “funny and uplifting and a bit sinister too—ambiguous I suppose”, Lucas not only summarises the exhibition but her four-decade-long artistic career. However, with the typical nonchalance we have come to know Lucas for, she insists she merely “fancied a two-word title”.

Sarah Lucas This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery © Sarah Lucas

Words by Grace Powell

All images courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery © Sarah Lucas

Special thanks to TATE Modern

Notifications