The Stadsstukken ’19 artist is reimagining the playground.

All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy—and NAZIF LOPULISSA refuses to be dull. The young Dutch artist explores the push and pull between imagination and reality, most recently focusing his practice on exploring the forms and structures found in children’s playgrounds. For Nazif, also (formerly) known as Nasbami, the playground is to be considered as a contradictory space, something that is meant to be innately playful and free, yet entirely reliant on calculation and design. Before health and safety took over play spaces, “imagination was the starting point”—and the artist is compelled to bring the viewer back to the start.

Dedicated to engaging the public on an imaginative level, it’s no wonder that Lopulissa makes a perfect match to Rotterdam’s youngest public art project, Stadsstukken. Running from 19th July until 22nd September for its 2019 edition, the project is focused on giving the fringes of the city the attention they deserve by asking 5 local artists—Nazif Lopulissa, Pip Passchier, Jasper van Doorn and (duo) Studio Bureau—to develop an installation for an overlooked site. Beyond tourist attractions and picturesque spots, the odd and the unseen is what truly shapes the identity of any place—and Stadsstukken’s ethos of shining light on the unique parts of the city provides an excellent way of getting to know Rotterdam like you had never seen it before. Stadsstukken wants to show the diversity and potential of these public spaces, and why they are important to keep amidst rising pressure for constant construction in an increasingly popular city.

Compelled to learn more, Glamcult called up Nazif a week ahead of installation to get some insights into his creative process. Lopulissa talks candidly about the highs and the lows of working big, his chosen site, the importance of public art and “wiggling through the bullshit” in life and art alike.

To start off I’d like to ask you about your chosen alias, Nasbami… Where does it come from and why do you choose to present your work under a moniker?

Well, I don’t use that anymore! Last year I had an exhibition at Kunsthal, and I thought I should work under my normal name. Nasbami is okay, but if I’m going to change in 10 years to my name then it’s going to be too hard to go back… Now everything’s starting and getting serious, so if I wanna go through with it and be serious about my career then I think there’s more value in working under my own name than some alias. It came from my friends; I was good at making bami, it was my favourite dish, and so one time they called me Nasbami. And then when you make an Instagram or a Facebook account and you don’t want to put up your actual name… so it just grew from there.

Your work deals with investigation of structures of objects and places from daily life, namely the playground as a space of contradiction… Could you introduce your practice and tell us about your inspiration and your way of working?

I used to work from assignment to assignment to assignment, and all different kinds of subjects—each project needed a new subject. But then I thought ‘what if I just become good in one subject and make it my own’, so I can do one big research and get 10 years of work out of one thing… So, last year I started to research playgrounds, the first research I did is what I showed in the Kunsthal: 36 paintings of shapes that I recognized from those places, and then tried to extract what interests me… Actually no, the first time I presented that research was at Unfair in Amsterdam, that was the first thing! I made a slide with a brick wall—it was not possible to climb the slide’s stairs because it was a brick wall instead. It was a comment on the situation in Holland now; the playgrounds are there but they are not very interesting.

What is the idea behind Wiggle Wiggle, your installation for Stadsstukken 2019?

The Wiggle Wiggle thing was originally the name of the project that did not make it. But then I was thinking the new project should have the same name, because in the city everything is dynamic and balanced with everything, and also it’s me, as a maker, struggling with changing the project. In the end you have to make it and wiggle through all the bullshit. I think its even better for this new project because initially it was just an aesthetic name, because you see the objects wiggle, but now it refers to the whole situation—wiggling through…

I’d like to talk about the location you are working with, Zuidplein. I looked at it on Google Maps and it feels like a very impersonal space, especially compared to other locations of this project… It’s kind of busy, there is a shopping centre, a local theatre, lots of vehicles, and then this overgrown island in the middle. Could you tell me more about your relationship to this spot and the resulting process? Was it assigned randomly? What exchange do you hope for between the work and the space once everything is installed?

We could choose what we respond to, what we’d like to do. One thing was, it couldn’t be in the city centre, we had to look around a bit, look at forgotten places of Rotterdam. In Zuidplein everything is happening, but you don’t have any time to look at what’s happening, you’re not focused—it’s so busy and crowded. I used to live in the street that ends there. They’re also going to renovate the whole shopping mall, so it’s millions pumped into this place… there’s something happening it seems. In the centre there’s already enough art, and if my work is reaching people in this district it’s better. You need a moment of rest in all this busyness, so maybe if you see art in this kind of place you get some time to observe… it’s a nostalgic thought.

I hope the viewers will see my ‘playground’ and have a thought about their own playground times. Aldo van Eyck, the godfather of the playground in the Netherlands, made structures that look like an igloo, but in that igloo there was no restricted way of playing, so it was all about the imagination of the kid—how can a kid play in something that’s not playable? Imagination was the starting point. Now the objects are all very easypeasy, there are slides, swings, there’s no time for imagination… I hope to make people interact with the objects in a more imaginative way.

And how do you see this relationship progressing? The work will be there for quite some time…

Yeah, 2 months! I think it’s a hard place so people might think twice before they place an artwork there, and I hope over time people see that it works—putting art in spaces that are not very attractive and where it wouldn’t normally go… I hope people will have questions about it also, why and what is standing here, and if they have a feeling about its meaning.

Building a public space installation is of course never without a struggle—as you mentioned already you had to make some adjustments and change the project, could you tell us more about that?

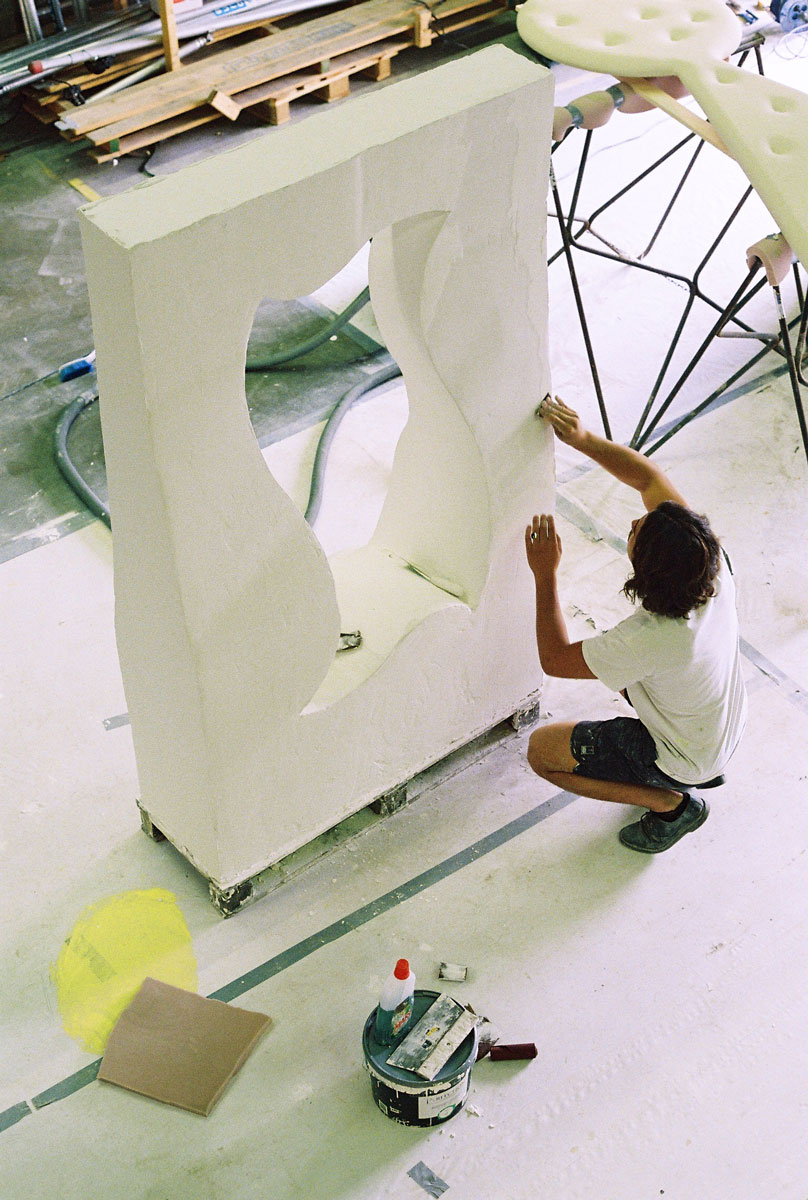

For now I have 5 objects that are roughly 2 meters high, but I am hoping to make more. The original objects were way too heavy, and I had to make it with 10 people, so the budget would skyrocket! Way too heavy, way too intense, so with two weeks left it was not possible to make it happen. I had to come up with a new plan that is still focused on the playground, I made a list of objects I wanted to make, that I collected through my research… and I’m working with wood, bricks, concrete blocks, foam, metal. That’s another thing about playgrounds, the contrast—it has to be playful but also very safe. What you then get is, for example, a metal beam mounted on a wood plate, and then covered with a rubber plate… total material contrast, what’s happening here?

Stadsstukken gives a unique look at the public spaces that Rotterdam has to offer and questions them by reflecting on their diversity and potential, giving ‘the fringes of the city the attention they deserve’. What is at stake here?

I think art in the public space is nice; instead of expecting people to go to museums, you can also bring museums to people, so it’s a good starting point to get people in contact with art. Normally art objects exist in a white cube, and now you put it into a pre-existing context and see how the environment reacts. The whole environment can get another meaning because of one object.

Could you tell us more about Rotterdam, and the future you see for it?

Rotterdam is growing a lot right now, both spatially and culturally. There’s a lot of funding for creative people, so they are trying! But at the same time everything is getting more expensive, so not all artists can afford it. Choices have to be made on ground level, we need more projects like Stadsstukken—sculptures in public spaces for normal people, and not just the rich. We need to make art for everybody.

You graduated 3 years ago now, from Willem de Kooning Academy. What’s the most precious lesson you have learned so far as an independent young artist?

Look at what you’re doing, reflect on your own working methods, invest in yourself – that’s the most interesting way to grow I think. Also sometimes you set the standards so high for yourself that the work is no longer possible, like in this situation, so it’s important to adapt- I had one day to set up a whole new plan. I don’t want to say that I was already breaking down and crying, but it was near… And it’s not that I’m working; I like what I do!

Words by Masha Ryabova

Photography by Hilde Speet

Follow Nazif Lopulissa on Instagram

Stadsstukken 2019 is on from July 19th until September 22nd in Rotterdam

[Sponsored Post]