“A critic once said I fail with dignity.”

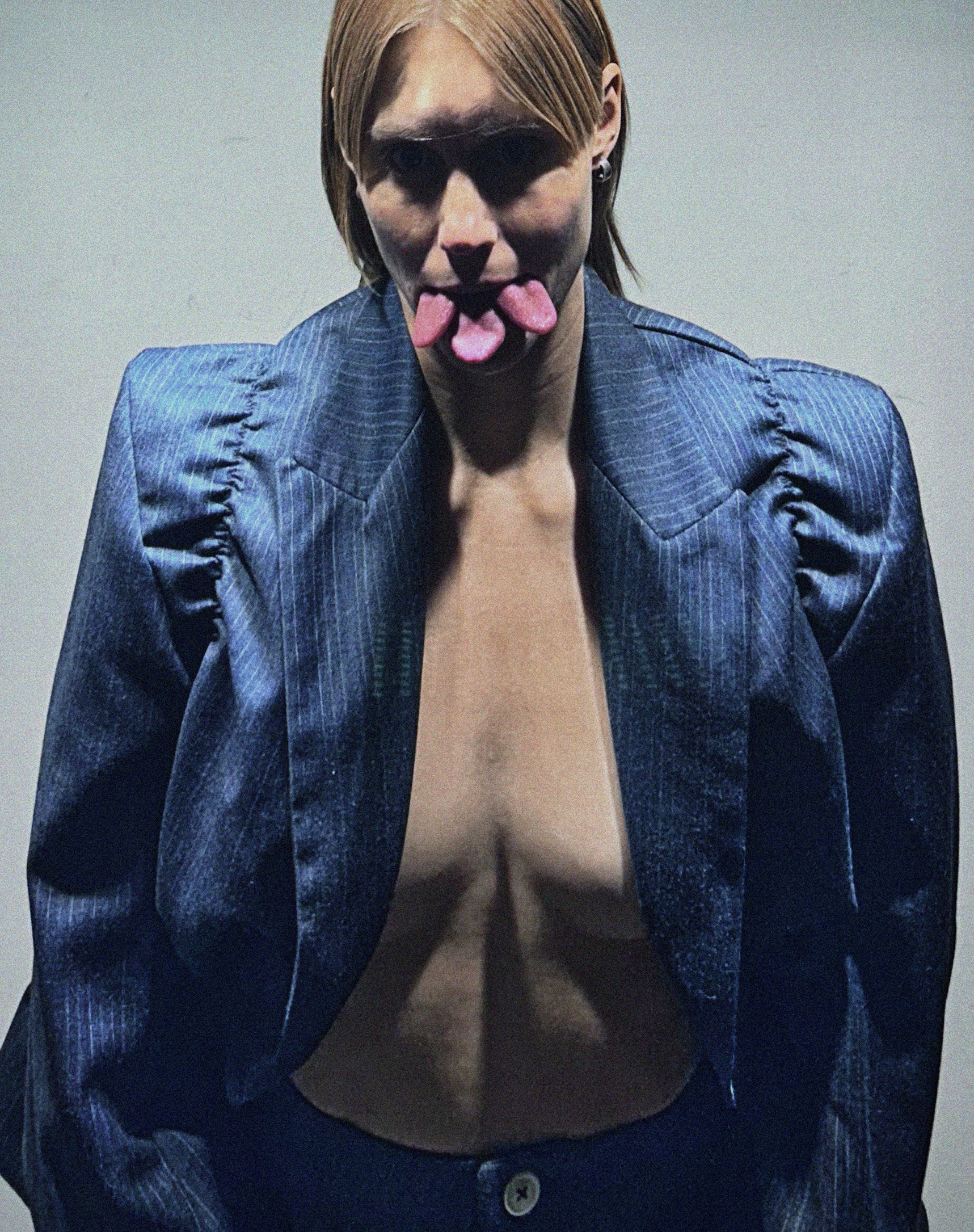

Plenty of tongues. A cacophony of voices. The steady rhythm of another echo. In A Mouthful of Tongues, Stina Force conveys a message of the many through tongues that well from her mouth. It’s wholly imbued with the punkish improvisation that characterizes the Swedish-born, Viennese-based performance artist and musician. A Mouthful of Tongues caresses the bounds of humor, the absurd, and sometimes the dark. Equipped with her voice and drums, she occupies the space with whatever sounds want to speak through her. Some guttural and visceral, others whimsical and playful. Wearing prosthetic tongues symbolizing the many versions of her inner self, Force attempts to speak, visibly constricted. You can’t help but experience the performance visually, but also tangibly- in your bones, along your spine, and nibbling on the crevices of your neck. Ninamounah welcomes Force in a conversation detailing the bounds between the performative and the genuine, the real and the fake. Oh, and of course, a classic garlic story.

Let’s start with the tongues. They appear, they speak, they move. What are they saying? And what are they doing there?

The tongues represent internal noise—many voices, different versions of self, layered thoughts. In A Mouthful of Tongues, I wear thirteen fake tongues in my mouth and try to speak. It’s absurd, uncomfortable, and kind of funny. The title came from a really bad erotic novel I found once. I stole the title and discarded the rest.

What’s your problem?

[Laughs] The tongues are cheap. I get them from a prank store that sells fake poop and vampire teeth. I love using trashy objects—they’re accessible, simple, and strange. Maybe my problem is that I always choose the most ridiculous props.

And when you perform these voices—where do they come from? Dreams, memories, spirits, ancestors?

I think they come from improvisation and deep listening. I try to open up and allow whatever wants to speak through me to come out. Sometimes it’s nonsense, sometimes it’s memory, sometimes it’s pure sound. I don’t want to control it too much. It’s like channeling but also parodying channeling. Somewhere between real and fake. That tension is the core.

And the drums… are they a voice too? Or are they separate from the ceremony?

The drum is a voice, definitely. It’s my timekeeper, my support system. When I play it, I feel like I have a spine—something holding me up. It lets me improvise vocally while staying grounded. I can scream, sing, babble, chant—anything—because the drum gives structure.

When I watch you perform—the tongues, the voices, the drum—your way of dressing is also so important. It really feels like a second skin. Why this kind of skin?

The suit I wear in A Mouthful of Tongues is intentionally stiff, corporate, and performative. It sets the stage, frames the body. I wanted something that says “serious speaker” while doing something totally unhinged. It becomes a costume of control that slowly unravels. I also wear cowboy boots because I do a mini line-dance at the end, and because they carry so much cultural weight—Western, gendered, tough, theatrical. Everything I wear points somewhere but never lands.

You’re very punk and rock, but also soft and sweet.

I like that contrast. I’ve been told I’m intimidating, but then I cry on stage or make weird jokes. I want to resist easy definitions. Punk isn’t about anger to me—it’s about doing what you care about on your own terms.

The spaces you perform in—they’re often strange, uncomfortable. That awkwardness, is it important?

Yes, I really value awkwardness. It opens up possibilities. If the audience is unsure of how to behave, they’re more present, more alert. I want to make spaces where things aren’t slick or smooth—where people can feel weird together.

You always do that story part too, right? Like the one about garlic?

I usually start with a 10-15 minute monologue that’s somewhere between stand-up and storytelling. It sets the tone. The garlic story is a classic—I’ve told it many times. It’s a good opener because it’s funny and just absurd enough to make people relax and lean in.

It helps break the audience.

Exactly. Once they laugh, once they let go a little, we can go somewhere stranger. It’s like a soft manipulation.

You call yourself a one-woman punk band. Why perform alone?Performing solo gives me freedom. I can change the structure on the spot, follow impulses, and rehearse whenever I want. I love collaboration, but I also love control. It’s a lot of work to do it alone, but it suits my temperament. I can obsess and be flexible at the same time.

What does failure mean to you? You seem open to mistakes.

Failure is part of the process. In clowning and improvisation, failure is often the most interesting moment. It’s when something real happens. I don’t mind failing on stage. I’d rather that than be boring. Failure, to me, is a site of connection.

Is there someone you perform for? A specific audience in mind?

I try to stay connected to myself and the space I’m in. I don’t aim to please a specific audience. I think about what the room needs, what I need, and where those two things meet. It’s more relational than targeted.

Because the photoshoot was focused on A Mouthful of Tongues, maybe you can share what you’re working on now?

I’m developing a new piece called Spöka. In Swedish, it means both “to haunt” and “to act ridiculous”—which feels perfect. It’s influenced by children’s TV, ghosts, and grotesque emotions. I’m also writing a long, looping erotic monologue about a mother-daughter relationship that’s intentionally disturbing and poetic. And I just started a noise duo with Maja Osojnik—bass, drums, vocals, chaos.

And if you had to give a few words to describe yourself and your work?Absurd. Fragile. Funny. Disturbing. A critic once said I “fail with dignity.” I think that’s perfect.

Just a blonde woman trying to have fun.

[laughter]

Introduction by Sharon Calistus

Interview by Ninamounah Langestraat

Photography by Louis Oomes

Clothing by Ninamounah Langestraat

Assistance by Cindy Hiekata

Notifications